Interactive Aleppo Map Helps Information-Sharing Amid the Chaos of Civil War

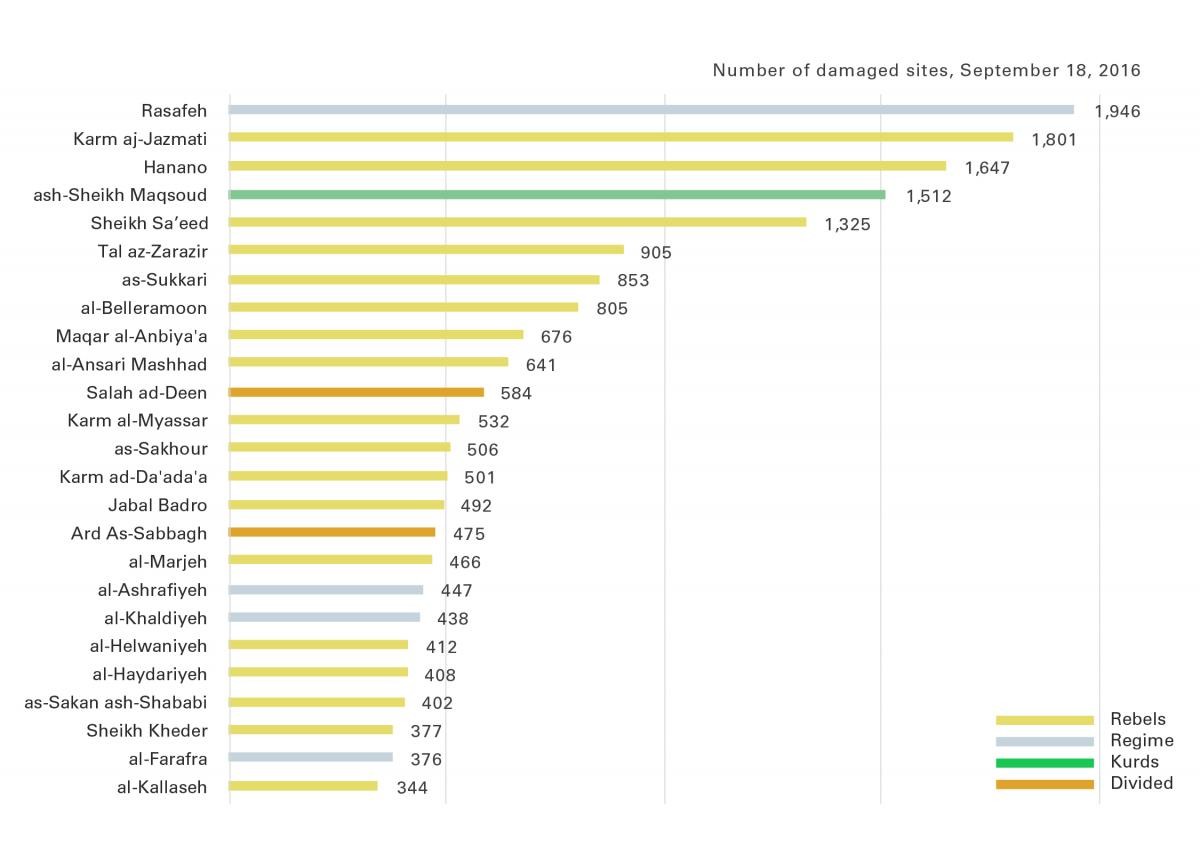

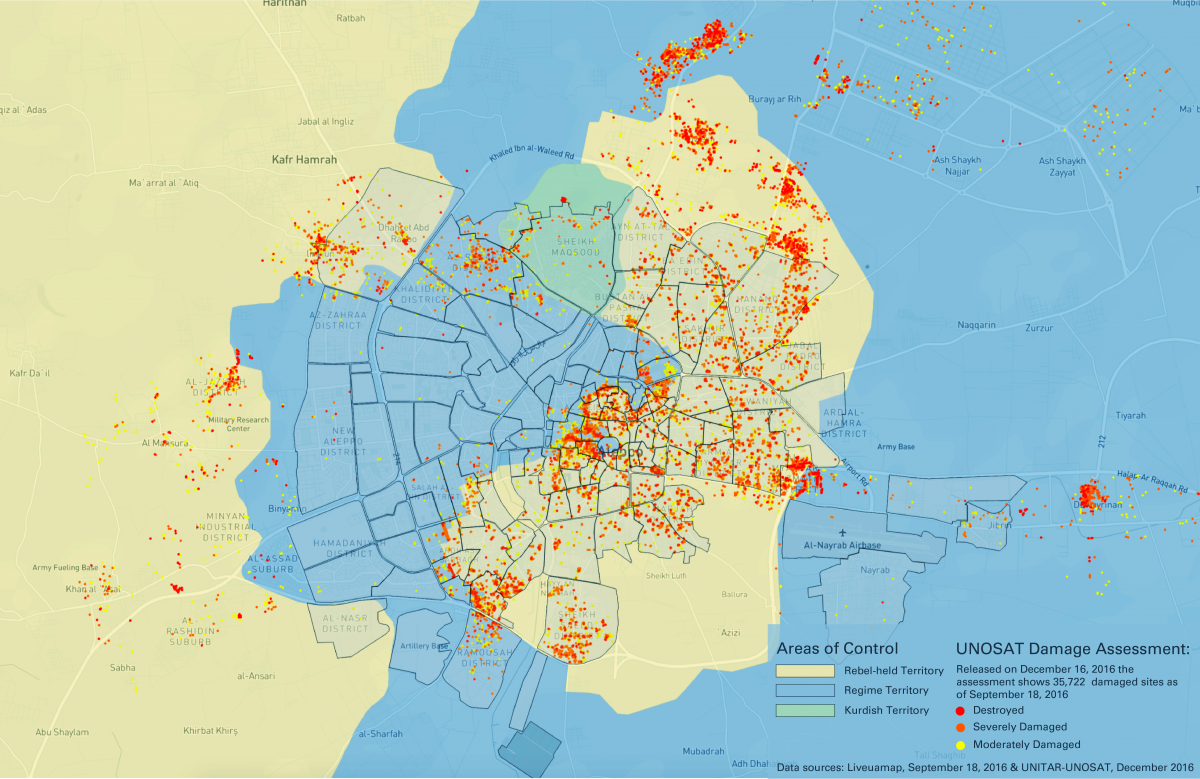

New data released by the United Nations Institute for Training and Research - Operational Satellite Applications Programme (UNITAR-UNOSAT) shows a stark pattern of destruction when overlaid on the zones of territory control in Aleppo: damaged sites identified by UNOSAT lie primarily within or just outside the outlines of the besieged areas in eastern Aleppo, confirming that this portion of the city has been systematically bombed and shelled for the duration of the war. View full interactive map

In nearly six years of civil war, the city of Aleppo, Syria’s one-time industrial hub, has become the center of a humanitarian catastrophe and the destruction of one of the oldest, culturally rich cities in the world.

As rebels struggle against government troops and civilians attempt to evacuate from the city, a number of international organizations, including the United Nations and UNESCO, are trying to preserve what is being left behind and a global cultural heritage that can be traced to the 6th millennium B.C.

Laura Kurgan, an associate professor at the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, is leading one such project, Conflict Urbanism: Aleppo, which is an evolving, interdisciplinary study of the destruction in the city that gives people—those in the city, those who have escaped, and those watching from afar—the ability to share information and view what is happening on the ground. As director of the Center for Spatial Research, Kurgan and her team have created an interactive, open-source map of Aleppo that combines layers of high-resolution satellite images with data gathered by human rights organizations and the United Nations.

Related

Professor Zainab Bahrani Helps Preserve Cultural Heritage in Iraq, Columbia News, Dec. 20, 2016

They accrue data about the physical destruction of the city and data about how urban warfare is tracked and monitored from a distance. Users can navigate Aleppo at the neighborhood scale, examine geo-located data about the damage and share their stories.

Kurgan is not the only Columbia faculty member working on the Syrian crisis. The International Observatory for Cultural Heritage was recently established at Columbia’s Italian Academy, and its 2016-2017 research fellows are all focusing on projects that address conservation and the contemporary destruction of art and architecture, such as at sites in Iraq and Syria where ISIS has targeted and destroyed structures associated with minority sects of Islam, Christianity and ancient cultures.

Q. Why did you choose to focus on Aleppo?

A. It’s the most important urban conflict right now, however you look at it: in terms of history, human rights or geopolitics. Aleppo was the largest Syrian city before the war and one of the oldest cities in the world, with a diverse cultural and religious heritage. It sits at the crossroads of several ancient trading routes and was at times ruled by the Assyrians, Mongols, Ottomans and others. There’s going to be an end to the war and the city will somehow emerge. We hope to be able to show what’s happened there.

Related: The Factory of Fakes, The New Yorker, Nov 28, 2016

Q. Your work was influenced by the Polish-Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin and by Robert Bevan’s book, The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War. What was their influence?

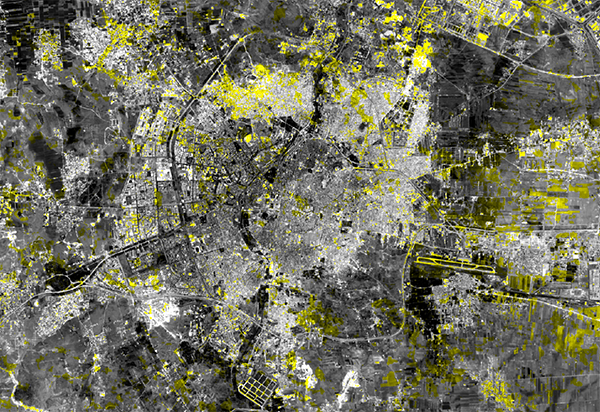

A. Lemkin’s conception of vandalism serves as a motivating rationale and a theoretical frame for this project. He coined the term “genocide” during World War II, which was codified in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide adopted by the United Nations in 1948. But as we learn in Bevan’s book, in 1933 Lemkin had already described genocide in terms of two interlinked concepts: barbarity and vandalism. He understood barbarity primarily as “acts of extermination” targeting “ethnic, religious or social collectivities,” and vandalism as the “systematic and organized destruction of the art and cultural heritage.” During the civil war in Syria, many buildings and neighborhoods in Aleppo have been destroyed. The four satellite images layered into our map tell some of the stories of this ongoing erasure and its varied aftermaths—deaths, departures and the reorganization of the urban landscape. We hope this aerial imagery, and the investigations developed to ask questions with it, can be linked with eyewitness and documentary accounts (social media are overflowing with those) to enable both understanding of and responses to what’s happening there.

Q. Is the map updated regularly?

A. Yes. In the spring of 2016, I taught a “Conflict Urbanism: Aleppo” seminar, and the map served as a research tool for that class. Students worked to develop case studies, specifically designed to research urban damage in Aleppo during the civil war, and added these as layers to the map. Their results covered such topics as water as a weapon of war, interior borders between fighting factions, imagining urban survival during wartime, imagining escape routes, cultural heritage, communications infrastructure and refugee camps at the borders. Throughout the summer and fall, we have continued to add more datasets and case studies to the project, including drone footage released by activists on the ground that offers new perspectives on the destruction.

Q. How is the map being used?

A. The map is open-source and interactive, at the neighborhood scale. Users can navigate the city, with the aid of high-resolution satellite imagery from before and during the current civil war, and explore geolocated data about cultural sites, neighborhoods and urban damage. We are inviting collaborators and students to bring new perspectives and analyses into the map. It’s a timeline of the war—how it unfolded and is continuing to unfold in Aleppo. What our project brings to this field of monitoring conflict in real time is an academic humanities approach. I’ve long been interested in how people other than professional geographers or cartographers work with maps, and how the world outside of the military and intelligence communities can employ satellite imagery. I wrote a book called Close Up at a Distance: Mapping, Technology and Politics, so I’ve been following the history of the use of satellite imagery for a long time. A map like this is a platform for storytelling with data. Every time you put a layer of data on it’s like adding another layer of truth, another narrative. That’s why I call it multidimensional. It might look flat and it might look like an overhead view, but there are actually a lot of different standpoints embedded in it. So it’s one of the few map resources that has this kind of timescale built into it.

Q. What is it like to work on this map in New York and yet be so intimately acquainted with what is happening in Aleppo?

A. It’s complicated, but it’s a symptom of our time, isn’t it? We’re not there, and yet we’re in touch all the time with people in the midst of a catastrophe, and we can see some of what they’re going through with shocking clarity. We are just trying to keep track of what’s happening in an honest, reliable, vigilant way. The frame we use is mapping, which we do carefully and critically and collaboratively—it’s a sort of engaged observation. When you get to know a city as well as we now know Aleppo, and witness what has been lost, you can’t really remain dispassionate.