Dr. Benjamin Schwartz, Cartoonist, Draws on Medical Training

Like the superheroes in the comic books he collected, Benjamin Schwartz (CC’ 03, P&S ’08) grew up feeling he had two identities.

He looked up to his father, a Columbia cardiologist who was passionate about his job. Schwartz considered medicine his default career, but his secret passion was cartooning. He doodled incessantly, filling sketchbook after sketchbook with drawings.

Growing up in Scarsdale, it never occurred to him that he could combine two such disparate careers. “How on earth do you become a cartoonist?” he said. “I knew people actually did this for a living, but it didn’t seem real.”

After earning a degree in psychology at Columbia College, he was admitted to the College of Physicians and Surgeons, where his father, Dr. Allan Schwartz, is the Seymour Milstein and Harold Ames Hatch Professor of Clinical Medicine and chief of the cardiology division.

At every step of the way, though, “it became more and more clear that this wasn’t the path that I wanted to be on,” he said. “I found myself having the same conversation over and over, `I just don’t know if this is really for me.’”

Then, in his senior year of medical school, Schwartz enrolled in a month-long elective in Narrative Medicine, a program at the intersection of medicine and the humanities that he credits with changing his life.

Today, the younger Dr. Schwartz is a cartoonist for The New Yorker, a lecturer in the University’s narrative medicine program and social media content producer for the medical school’s Department of Surgery. He is also developing a comic-based curriculum for Columbia’s Department of Ophthalmology.

The Program in Narrative Medicine oversees a required curriculum at the medical school and is also a master’s degree-granting program designed to teach medical students, writers and practicing clinicians the skills necessary to listen to and understand their patients’ complex stories, says Rita Charon, its executive director and a professor of clinical medicine.

Initially the curriculum focused mainly on reading novels and writing essays. Charon credits Schwartz, who illustrated a children’s book for a class project, with helping her realize the program was too focused on words, and that the visual arts have an important role to play.

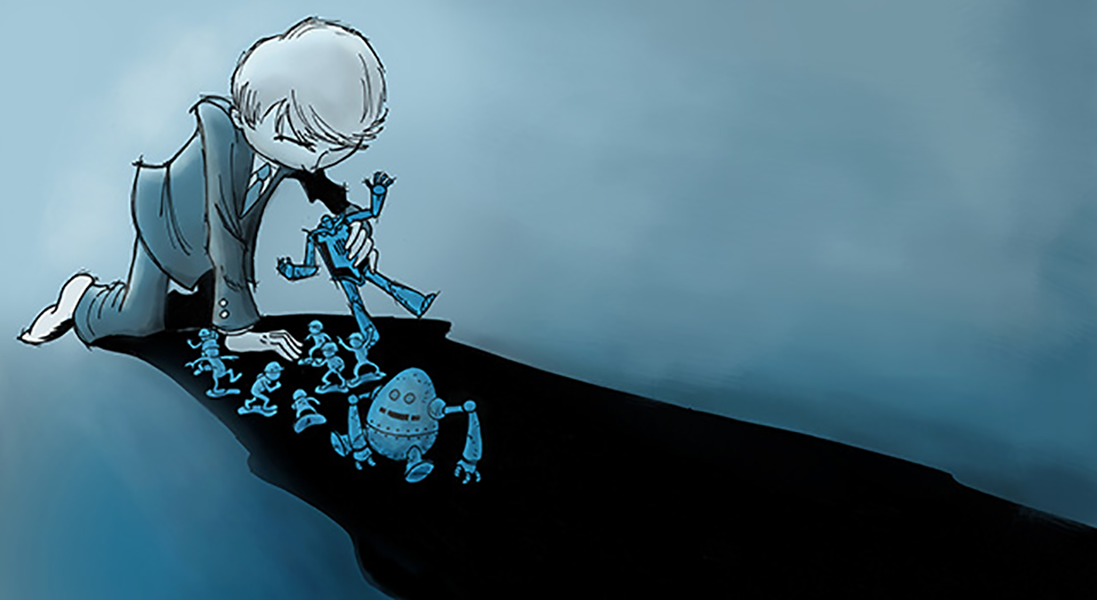

The book, written by Schwartz with two classmates, tells the story of a little boy whose mother dies, and was written to help children come to grips with a death in the family. “It was the first time any of the narrative medicine students had done anything like this, and it was profound,” said Charon.

Schwartz said putting together that book was the most fulfilling experience he had in medical school. He had found his own superpower, and Charon recognized it.

Today, the narrative medicine students can write plays, make videos, take photographs or draw for their projects. Charon has also incorporated trips to art museums and other cultural institutions.

Schwartz continued his cartooning quest, and in 2011 went to The New Yorker’s offices in Manhattan and met its cartoon editor, Bob Mankoff. The two hit it off, meeting weekly over six months to go over Schwartz’s pitches.

Image Carousel with 7 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

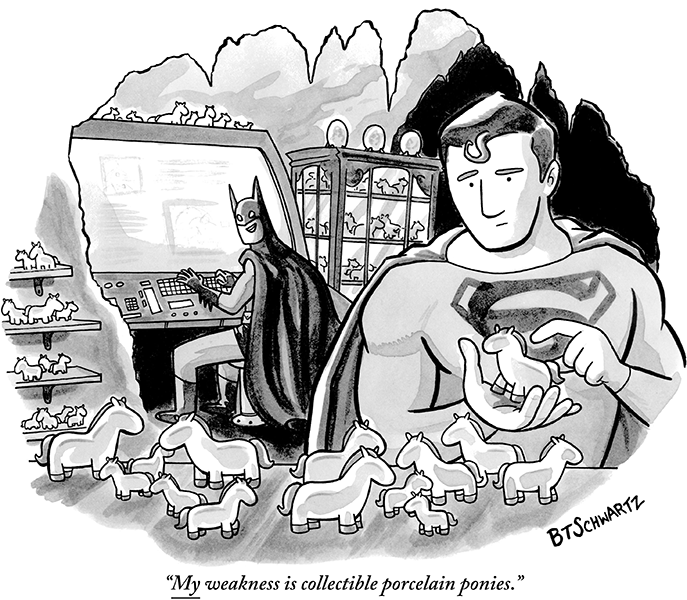

Slide 1: Batman to Superman: My weakness is collectible porcelain ponies

-

Slide 2: Clown crawling through desert, calling Seltzer...seltzer

-

Slide 3: About your cat, Mr Schrodinger, I have good news and bad news

-

Slide 4: The gluten's back. And it's pissed.

-

Slide 5: Child playing with toys

-

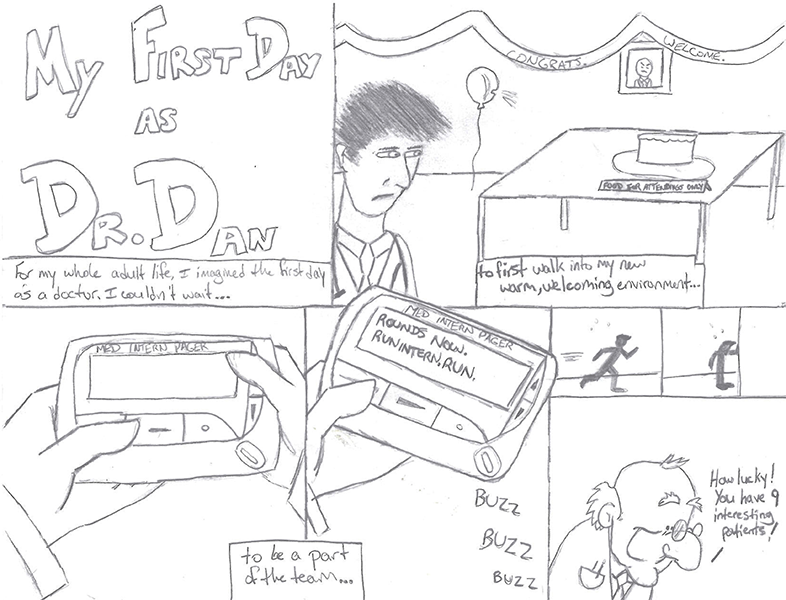

Slide 6: My first day as Dr. Dan

-

Slide 7: Meducation

“The fact that Ben quit medicine to be a New Yorker cartoonist showed me he had the requisite desire to put up with the rejection required of such a quest,” said Mankoff. “What I saw in Ben, besides that, was a facility in drawing that was ideally suited to the graphic vocabulary that cartoons need. Oh, and did I mention he’s funny? Much too funny to be a doctor.”

Schwartz’s first cartoon appeared in the magazine’s Dec. 12, 2011 issue. It was single-panel comic depicting a clown dragging himself across a burning desert, crying out, “Seltzer … seltzer!” Seeing it published was the happiest day of his life, Schwartz said. Since then, he has published 80 more.

A year later, Schwartz was invited back to the narrative medicine program to teach classes in comic book storytelling. His New Yorker work has made him more mindful of how he draws, a lesson he imparts to his students, encouraging them to take complex topics, pinpoint the crucial features and figure out how to organize the information in a story. He believes the process will help students become better communicators and more empathetic listeners – both goals of the narrative medicine program.

Schwartz also wants his students to become more reflective and self-aware, qualities he had to develop as he struggled to reconcile his love of drawing and commitment to medicine.

“I think it’s neat I have a kind of secret identity at the med school. Sometimes I wonder what the students would think if they saw my New Yorker cartoons,” says Schwartz, a devoted Spider-Man fan who agrees with what Uncle Ben tells the young Peter Parker: “With great power comes great responsibility.”

“Even though I am not a superhero in any way,” he adds, “I do enjoy having a secret identity.”