Frankenstein Comes to Life at Columbia

Beware! A monster was spotted on campus. Fearless and powerful, he has exerted an outsize influence on literature, stage, screen, comic books and literary discourse.

He is, of course, the central figure in Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s groundbreaking novel Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus. On Oct. 22, faculty from the Department of English and Comparative Literature gathered at Columbia’s Society of Fellows and Heyman Center for the Humanities to discuss the cultural legacy of this classic on the bicentennial of its publishing.

Written by an 18-year-old Shelley in a ghost story competition with the greatest poets of the age—Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley—the book set the stage for modern horror stories, according to Arden Hegele, a fellow in the Society of Fellows who organized the panel.

“In the two centuries since its publication, readers have variously interpreted Frankenstein as a cautionary tale of scientific hubris, an allegory of motherhood, a political commentary, and a gothic horror,” said Hegele. “More than any other novel, Mary Shelley’s book deals with the pleasures and perils of defying death.”

Mary Shelley wrote the book with input by Percy Shelley, whom she married while the work was in progress. He “shaped the novel’s place in the literary canon and wrote the preface, which asserted the intellectual seriousness of Frankenstein,” Hegele said.

That year—1816—was momentous for another reason. A volcano eruption in Indonesia the prior spring spewed so much ash into the sky that particles spread around the world and blocked the sun on multiple continents. Temperatures dropped, crops failed, people starved and rain fell in torrents. Many called it the year without summer.

Related Story

On a stormy night on Lake Geneva, Shelley, her future husband and Byron started their writing contest. Hers featured a creature brought to life in a laboratory and rejected by society, who then kills his creator, Victor Frankenstein. (The creature is given no name.)

“There’s a strange entanglement of climate and narrative that is integral to the structure of the narrative,” said Joseph G. Albernaz, a professor whose expertise is Romantic poetry. “There are grim mirrorings of our climate future. Both Victor Frankenstein and his creature die from extremes in temperature.”

The panel was part of the “Explorations in the Medical Humanities” series at the Society of Fellows. The Heyman Center co-sponsored the event with the Nineteenth-Century Colloquium at Columbia.

James Eli Adams, whose areas of interest include 19th century British literature and culture as well as gender and sexuality, said that the monster “seems absolutely desperate for a sense of connection. That’s part of what makes the experience of his loneliness in this novel so terrifying and riveting.”

The original creature was cultured and erudite. He learned English, could read German and French, and knew works of literature such as Milton; a far cry from largely inarticulate renditions in subsequent spinoffs—thousands of films, television shows, plays, books, music, comics, videos, merchandise and toys. But the original and his subsequent iterations usually share the same fate of loneliness and rejection.

At the Heyman Center panel, graduate student Milan Terlunen pointed out that if one filters out all the images from films (neck bolts, scars and green skin) and focus on the novel’s description (tall and strong with flowing black hair), “He’s hot.”

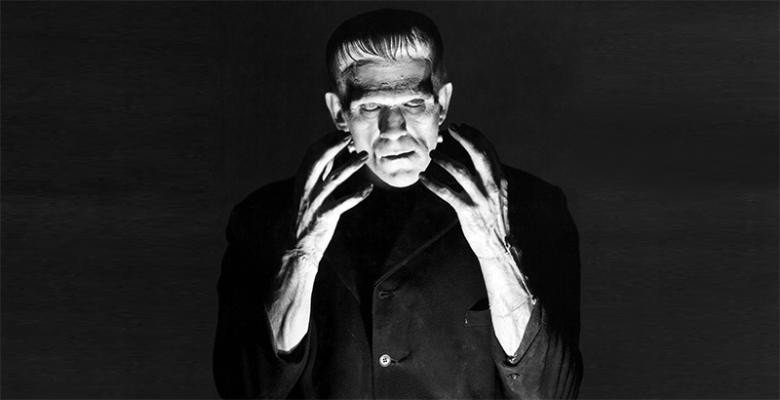

One of the most enduring cultural renditions plays against this reading of the novel. The best known image for the modern age is Boris Karloff’s rendition in the films Frankenstein (1931), The Son of Frankenstein (1939) and The Bride of Frankenstein (1942), the last of which featured actress Elsa Lanchester sporting a now iconic beehive with lightning bolt-shaped white streaks. She, too, rejects the creature—Karloff in 48 pounds of clothing and make up, towering on four-inch elevator boots.

Frankenstein’s monster first came to screens in a 1910 silent film. Subsequent movies have featured directors as diverse as Roger Corman, Mel Brooks and Kenneth Branagh with stars as famous as Robert De Niro and John Hurt and as unlikely as Abbott and Costello. Yet another film version is in the planning stages, this one by the Mexican filmmaker Guillermo del Toro, who won Academy Awards in 2018 (best director and picture) for The Shape of Water.

In popular culture, the monster has refused to die. He’s tussled with Bugs Bunny, inspired characters in the 1960s sitcoms The Munsters and The Addams Family, starred opposite The Flintstones as “Frankenstone,” appeared in The Beatles' 1968 animated feature, Yellow Submarine, and even reached kitchen tables in the strawberry-flavored cereal, Franken Berry.

“If the last 200 years have taught us anything, it’s that Frankenstein is an immortal book,” said Hegele.