The subject of the hugely popular show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art immortalized alumni, faculty and neighbors in her groundbreaking work.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

The subject of the hugely popular show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art immortalized alumni, faculty and neighbors in her groundbreaking work.

After the Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition closes on August 1, People Come First will travel to Spain’s Guggenheim Bilbao (September 17, 2021–January 23, 2022) and the de Young museum of San Francisco (March 12, 2022–July 10, 2022).

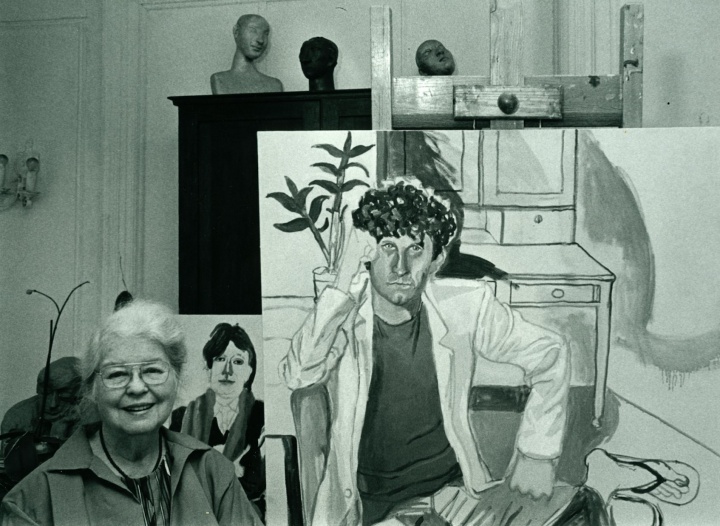

UPI / Alamy Stock Photo

Alice Neel in 1972.

Sam Brody

Gradually, the wheel turned. In 1974, the Whitney Museum showcased Neel’s work in her first major museum exhibition. Between then and her death 10 years later at 84, her star continued to rise. She was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, exhibited widely in group and solo shows, honored at the White House, and commissioned to paint the official portrait of New York Mayor Ed Koch; she even appeared twice on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson. (He was clearly charmed.)

Neel in her home studio, 1980.

© Harvey Stein. All rights reserved.

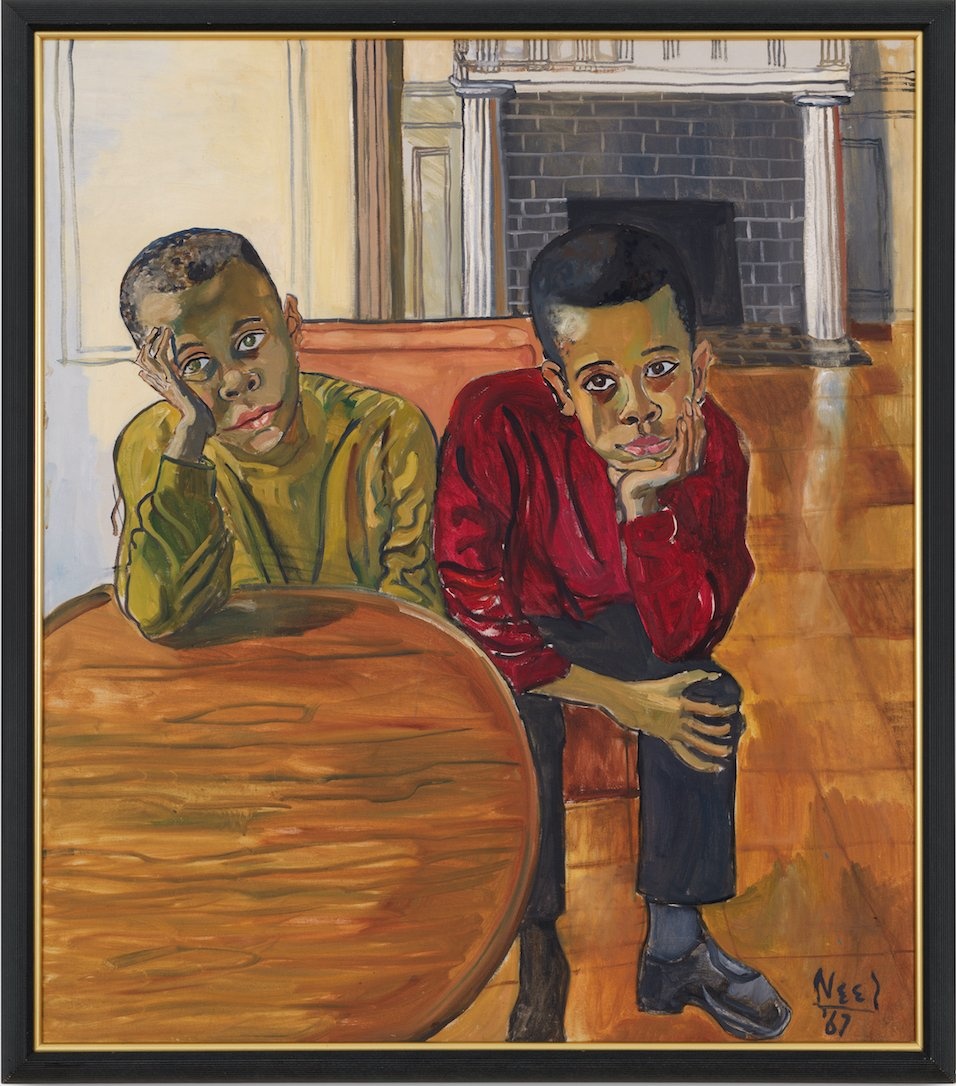

Hartley and Andrew Neel (1983)

© The Estate of Alice Neel

Neel often painted family members, Morningside neighbors and friends, among them Ed Ziff ’63 and Barnett “Jerry” Sokol SEAS’63, GSAS’75. She frequented Ideal, the Cuban restaurant then on 109th Street, and couldn’t resist the family-crafted delectables at Mondel Chocolates on Broadway. She also maintained a keen interest in her sons’ curricula, including the Core. “Alice sort of commandeered all our textbooks and made them her own, her library,” Richard says. “She was very interested in what we were studying. Absolutely, totally interested in it.”

A number of other Neel family members also share connections with Columbia. Hartley’s wife, Ginny Neel TC’69, has become a principal steward of Alice’s artistic legacy; their son, Andrew Neel ’01, is a filmmaker, and their daughter Elizabeth Neel SOA’07 is a successful artist in her own right. Richard’s first wife, Nancy Neel PS’63, was Alice’s longtime assistant; his current wife is Constance Hoguet Neel TC’69.

In addition to family members and Columbia alumni, Neel painted faculty luminaries such as art historian Meyer Schapiro CC 1924, GSAS 1935 and composer Jack Beeson. The following is a sample of Alice Neel’s Columbia-related works.

© The Estate of Alice Neel

“There’s great affection and warmth in it,” Hartley Neel ’63 says. “In those days we were absolutely as close as you can imagine. Things were good, and Alice enjoyed doing that painting.”

Richard Neel ’61, LAW’64 adds: “I’m glad Alice did it. Later on, she wanted to paint us in our Columbia Glee Club tuxedos, but she didn’t. It was just a concept.”

© The Estate of Alice Neel, Courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel and David Zwirner

When brothers Jeff and Toby Neal were 8 and 9 years old, they played basketball in a Harlem summer program supervised by Allen Tobias ’64, who lived near Alice Neel and had struck up a friendship with her. One day he dropped by her apartment with the Neal brothers, who were persuaded to sit for this now-famous portrait — though perhaps not with unalloyed enthusiasm, as the picture reveals. Snacks helped to buoy the boys through many sittings, however. “She was really bubbly, friendly, warm, interested in people,” Tobias says.

For many years Tobias tried in vain to locate the painting, which finally resurfaced about five years ago and was included in the Met exhibition. Toby Neal died in 2010, but Jeff and his family were invited by the Neels, along with Tobias, to a private viewing in advance of the Met opening — a reunion covered by John Leland ’81 in the The New York Times. It was the first time Jeff Neal had ever seen the finished work.

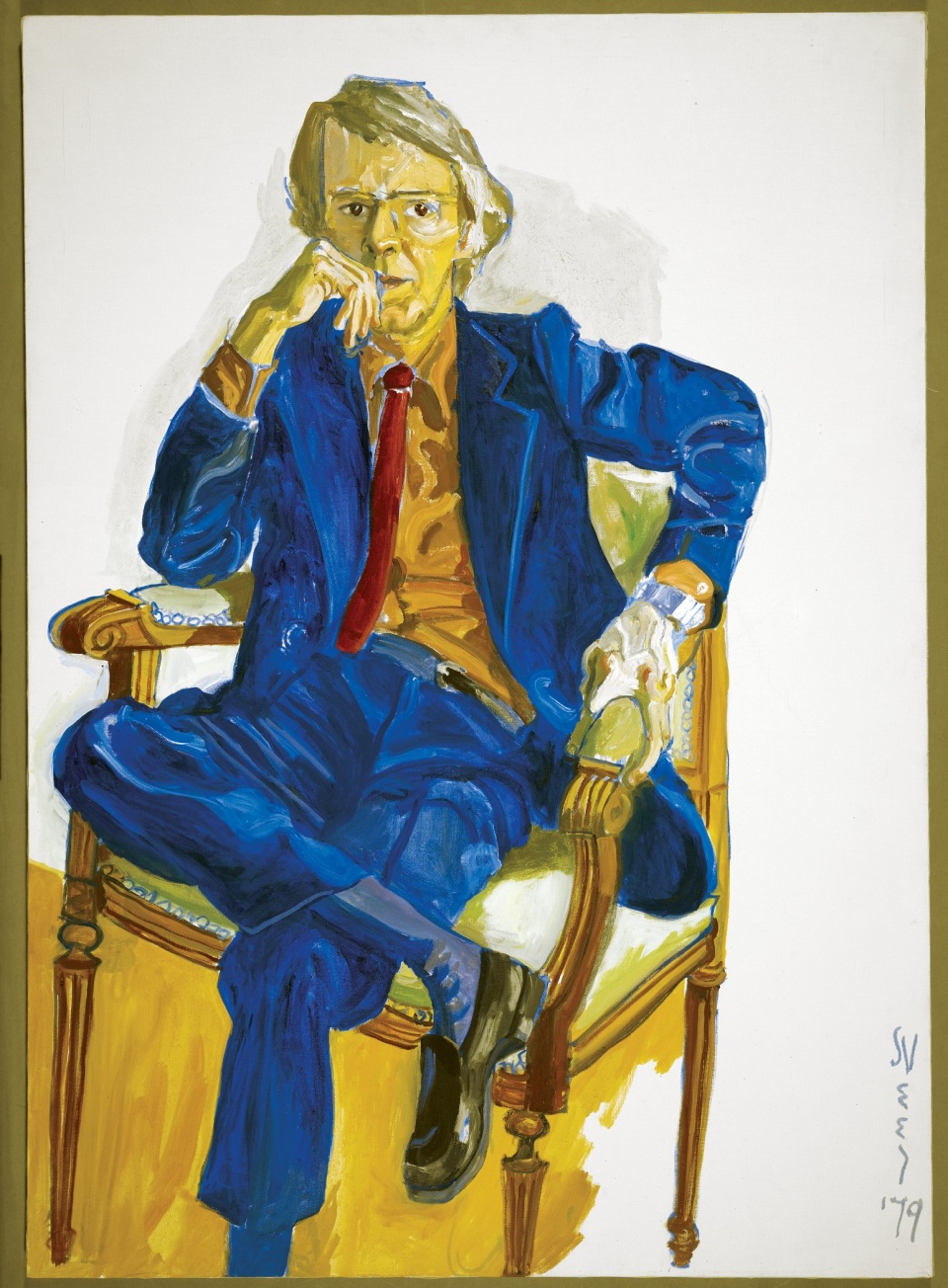

© The Estate of Alice Neel

Jack Beeson (1921–2010), a former MacDowell Professor of Music, was renowned as a teacher and composer, and was best known for his 1967 opera, Lizzie Borden. He met Alice Neel in 1976 when both were inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and they became friends.

Richard Neel had met Beeson many years earlier, however. “He was my Music Hum professor in my freshman year,” Neel says. “Later on, we came to know him quite well. I said to him, ‘Jack, you should buy that painting. It’s a great painting of you.’ He didn’t take my advice.”

The portrait was donated to Columbia by Alice Neel’s estate in 1999 and now hangs in the Gabe M. Wiener Music and Arts Library in Dodge Hall.

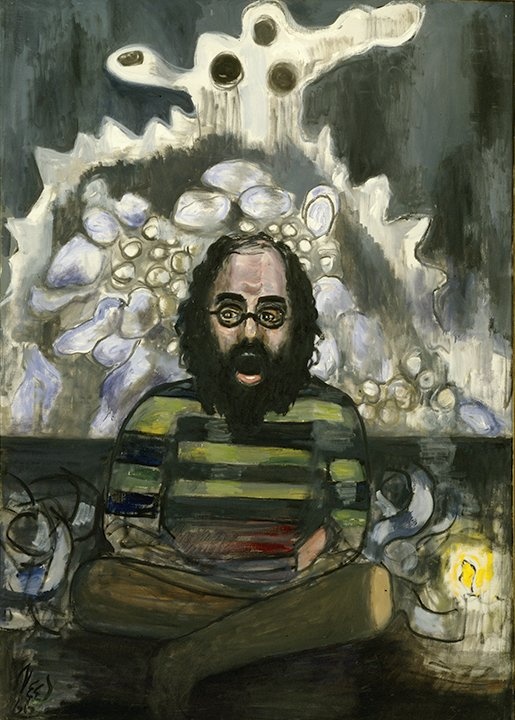

© The Estate of Alice Neel

Neel became something of an underground cult figure after she appeared in the 1959 arthouse movie Pull My Daisy, which engaged a cavalcade of Beat talents, including Allen Ginsberg ’48 and Jack Kerouac ’44. Alice makes a cameo, playing “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” on a small pump organ.

When she first met Ginsberg and other cast members, Patricia Hills, author of Alice Neel (1981), tells us, Alice didn’t recognize him. “Oh, are you taking the part of Allen Ginsberg?” she asked. “No, I am Allen Ginsberg.”

They remained friends. At Neel’s memorial service at the Whitney Museum in 1985, Ginsberg read his poem “White Shroud,” originally written for his mother. “It was very tender and caring,” remembers Ginny Neel TC’69, Alice’s daughter-in-law.

This phantasmagorical portrait was one of Neel’s “memory paintings,” Ginny says. “These were done in recollection of someone, without a sitting, and usually reflected her feelings about the person rather than her actual connection to them. I imagine that the background evokes LSD mind hallucinations.”

© The Estate of Alice Neel

This view from the window of Alice Neel’s apartment seems oddly cropped — no street, almost no sky — focusing our eyes on a harmonious composition of shapes and colors, light and shadow. Alice told art historian Patricia Hills that she thought of it as “the shadow of death.”

“It’s a beautiful piece,” says Hartley Neel. “It has elements of abstraction in it. It is gorgeously done in terms of the detail of the windows and the shadow of our building, which seems to be moving as you look at it.”

He and his brother, Richard, have fond memories of living there as students, just a short walk from campus.

© The Estate of Alice Neel

Dewald Strauss was a familiar figure in his West 100s door-to-door sales territory, and Alice Neel was one of his customers. Something about him struck a chord, so she asked Strauss to sit for a portrait. “She loved this painting,” Richard Neel says. “She commented on it a lot.”

As they chatted, Neel learned that he had been sent to Dachau concentration camp in November 1938; averting the fate of so many German Jews, Strauss emigrated to the United States the following year. He joined the Army in 1942 and earned a Purple Heart and Bronze Star at the Battle of the Bulge. After the war, he married, settled in Washington Heights and had two sons: Larry Strauss SEAS’73 and Jerry Strauss ’77.

Last year Jerry published a book, Giving My Father Back His Name: The Fuller Brush Man Meets the Great American Portrait Artist, about his father’s life and posthumous portrait fame [see “A Son’s Quest”].

© The Estate of Alice Neel

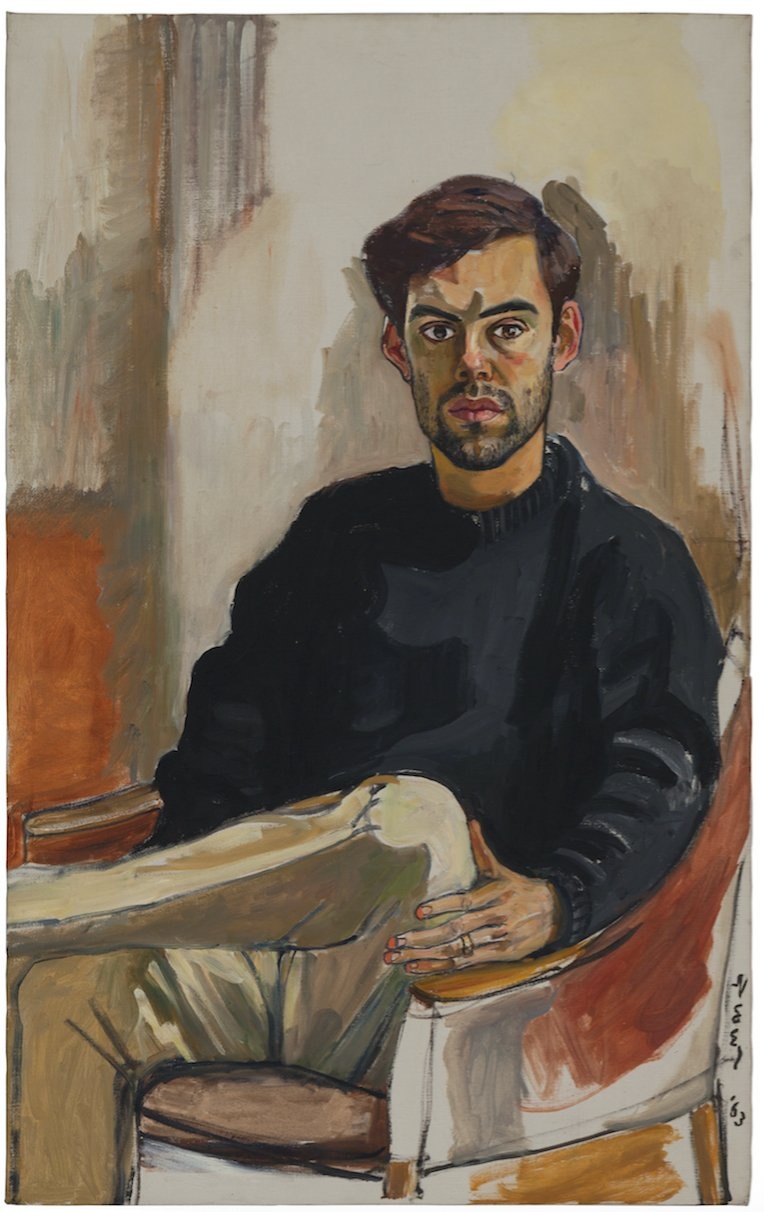

Richard Neel sat for his mother at a stressful moment in his academic career: His intensity is clear from the look in his eyes, the careful rendering of his mouth, the three-day beard.

“I’m in the Law School here, studying for finals,” he remembers, “and I figured out that if I didn’t shave, I would save 20 minutes a day. The extra time would be used for studying.” He has long appreciated how well Alice understood and expressed his state of mind. The canvas hung over the piano in his Riverside Drive apartment for many years.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Gift of Arthur M. Billowa. © The Estate of Alice Neel.

There’s no mistaking Hartley Neel’s troubled state of mind in this portrait. The distant stare and downcast mouth, each so finely detailed; his weighed-down slouch, arms akimbo; the deathly, ashen-green highlights on his face, his arms and the folds of his chinos. He was at a low point psychologically, Hartley says, and his mother captured it.

Then 25, he was a first-year med student at Tufts, having just finished two years of teaching at Dartmouth while he completed a master’s in chemistry. At home for the Christmas holiday, he felt disillusioned and conflicted. What disturbed him most was the experience of dissecting cadavers in his gross anatomy class. He wondered if he should drop out, which would probably mean getting drafted into the military just as the Vietnam War was escalating. “Fortunately, I went back to school, finished up and got excited about medicine.” He is still a practicing radiologist.

© The Estate of Alice Neel

A familiar vista to anyone who has gazed westward from uptown Manhattan to the Hudson River Palisades, this expansive work stands in contrast to Alice Neel’s many figurative works.

“This one is very abstract, very alive,” says Hartley Neel. “If you look at the light on the water, it has a magic feeling to it.”

Appropriately enough, the painting hung in the Riverside Drive apartment where Richard Neel lived for many years.

© The Estate of Alice Neel

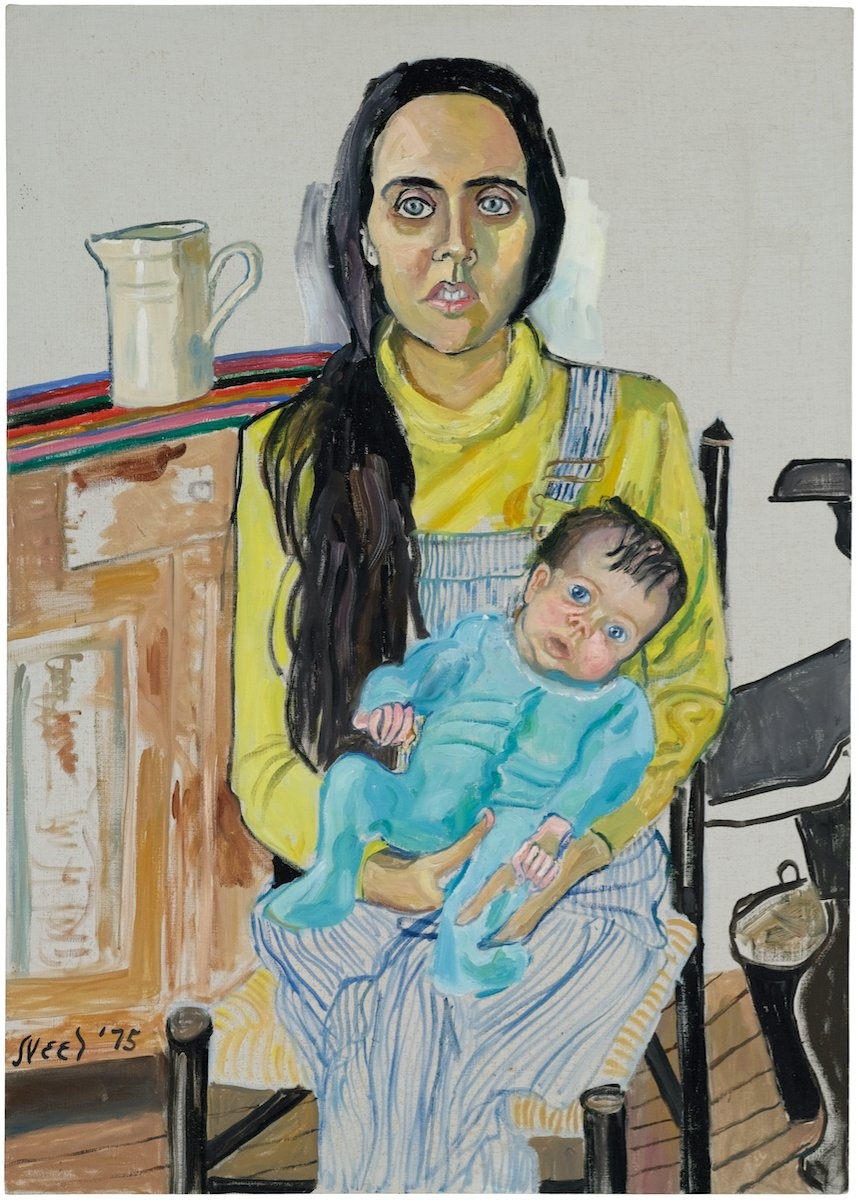

“I just love this painting,” says Ginny Neel TC’69, who married Hartley Neel in 1970. “It shows both the intimacy and the reality of motherhood. We both look tired, and there’s some squirming going on, and I’m trying to keep still. But we’re having a wonderful time together. She was an amazing little baby.”

At that time, Ginny says, “We were living in a 30-x-30-foot house on a dirt road in Vermont. Hartley was working almost 24 hours a day and Alice was wonderful, amazing. She’d come up and help. To set up her easel, I had to push a table out of the way.”

Elizabeth Neel SOA’07 grew up to become a painter and sculptor; her works are in the permanent collections of the Cornell Museum of Art in Syracuse; the Albright-Knox Museum in Buffalo; and the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles.

Former CCT editor Jamie Katz ’72, BUS’80 has held senior editorial positions at People, Vibe and Latina magazines and is a longtime contributor to Smithsonian Magazine. We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the Neel family and the Estate of Alice Neel in preparing this article; we also thank Allen Tobias ’64, who first alerted us to Neel’s many links to Columbia.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu