Exhibition Unpacks the Gems in Frank Lloyd Wright Archive

Frank Lloyd Wright was one of the first starchitects.

A preeminent 20th century designer, Wright pioneered the Prairie School style of architecture and built such iconic structures as Fallingwater in Mill Run, Pennsylvania, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City. To mark the 150th anniversary of his birth this month, Columbia's Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library and the Museum of Modern Art, the joint stewards of Wright’s archives, are presenting Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive.

“What more is there to say about Wright, this protean figure who had a 70-year career and designed more than 1,000 buildings, about half of which were built?” said Barry Bergdoll, the Meyer Schapiro Professor of Art History and Archaeology at Columbia and a curator in the Museum of Modern Art’s Department of Architecture and Design, who organized the exhibition with Jennifer Gray, a 2011 alumna of Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation who now works at MoMA.

Bergdoll realized that the best way to showcase the monumental scale of the archive—55,000 drawings, 300,000 sheets of correspondence, 125,000 photographs, 2,700 manuscripts and other materials—was not through a retrospective of Wright’s masterpieces, but an exhibition that was designed as more of an anthology. He invited a group of scholars to explore the collection, asking each to select and study an object or cluster of objects. The resulting exhibition consists of 12 sections, each curated by one or more of the scholars.

Related: CU People: Janet Parks, Curator and Archivist, Columbia News, June 21, 2017

“We arrived at the concept or trope of unpacking the archive, which represents both the literal unpacking of Wright’s archive after it arrived at Avery Library in 2013 and the metaphor of intellectually unpacking all of the richness that we found,” said Avery Director Carole Ann Fabian, who worked with Bergdoll on the exhibition.

The show features about 450 works dating from the 1890s through the 1950s, including everything from drawings, models, building fragments and furniture to film, textiles, photographs and scrapbooks. Some items have rarely or never been publicly displayed.

“You don’t think of scholarship as an action sport, with people running around and making connections, but, in fact, it is,” said Bergdoll, who structured Frank Lloyd Wright at 150 around a space that functions as a chronological spine to highlight many of the architect’s major projects. Rooms for each section branch off this central gallery, and each section is introduced by a short film in which the guest curators—many of whom are not Wright specialists—discuss the objects they chose and why. The films illuminate the period in which Wright lived, touching on issues of race, class, media, politics, education and the environment that still resonate today.

Video by Columbia News Video Team

Image Carousel with 6 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

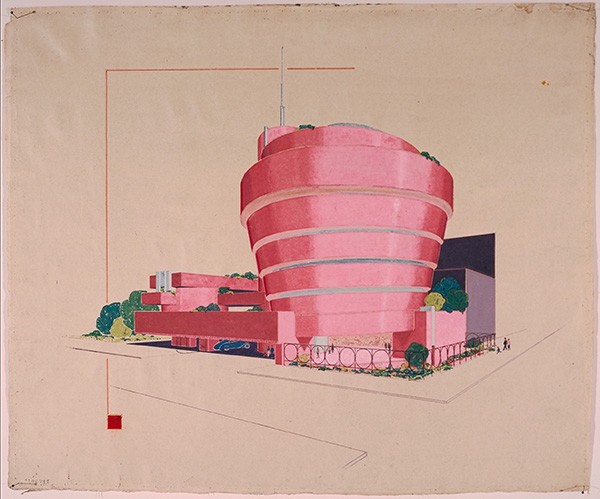

Slide 1: pinkish swirl shaped architectural design of a building

-

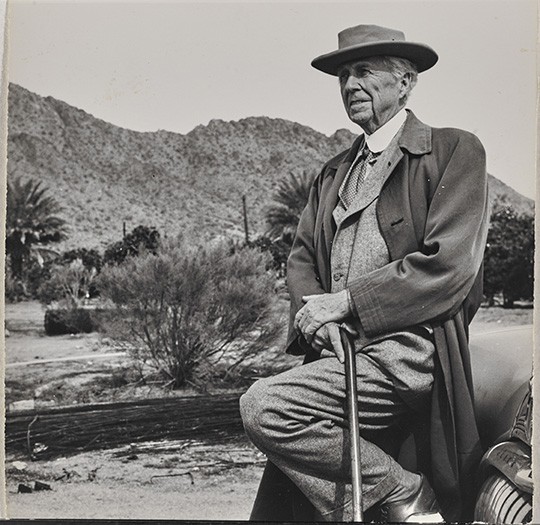

Slide 2: Frank Lloyd Wright. Undated photograph. Image Courtesy of The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

-

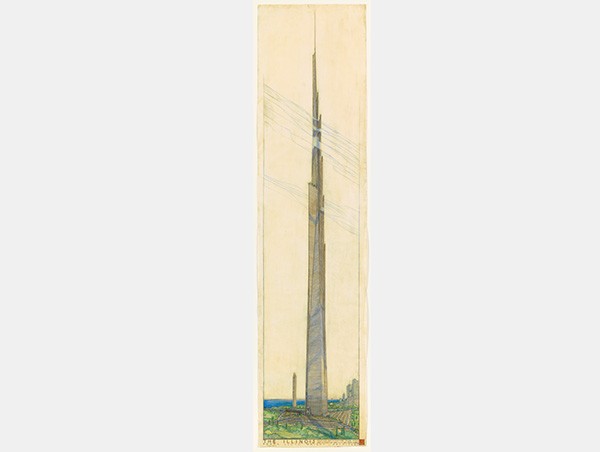

Slide 3: The Mile-High Illinois (Chicago, Illinois). Unbuilt Project. 1956. Pencil, colored pencil, ink, and gold ink on tracing paper. Image Courtesy of The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

-

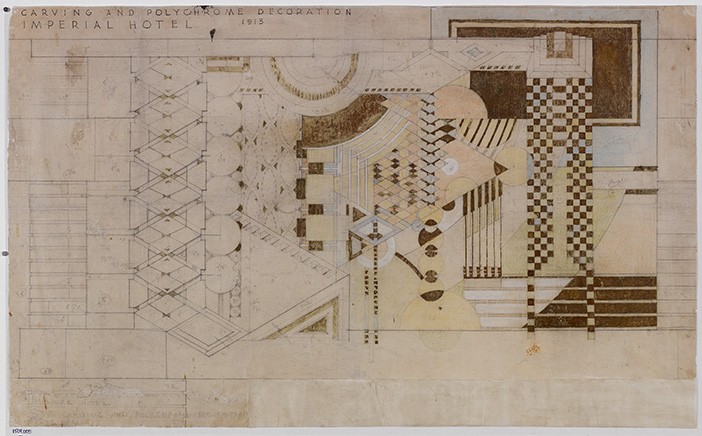

Slide 4: Imperial Hotel (Tokyo, Japan). Demolished 1968, Scheme 2. Paint, pencil, and colored pencil on tracing paper.Image Courtesy of The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

-

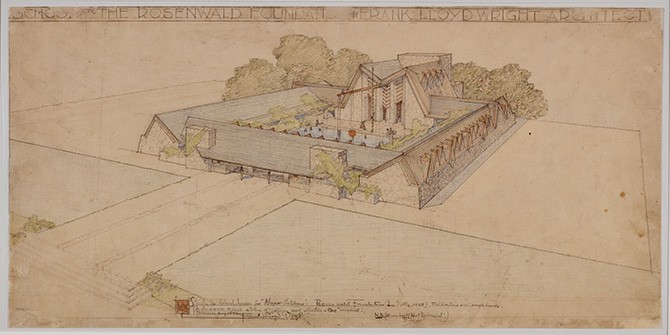

Slide 5: Rosenwald Fund School (Hampton, Virginia). Unbuilt Project. 1928. Pencil and colored pencil on tracing paper. Image Courtesy of The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

-

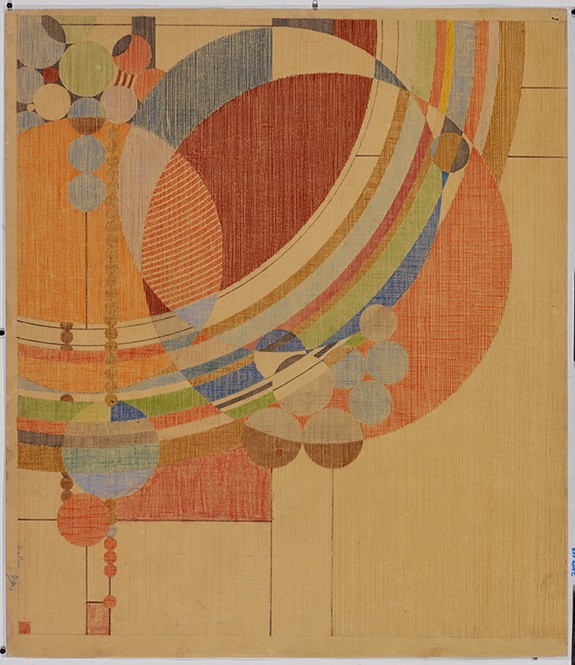

Slide 6: Frank Lloyd Wright. March Balloons. 1955. Drawing based on a c. 1926 design for Liberty Magazine. Colored pencil on paper. Image Courtesy of The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

In one section, Mabel O. Wilson, a professor at Columbia’s architecture school, researched a little-known 1928 design that Wright completed for the Rosenwald Fund, which focused on arts and education among African Americans and was developing a project to subsidize the construction of rural schools throughout the segregated South. Wright’s design replaced traditional clapboard schoolhouses with structures that the students were intended to help build, making hands-on labor an integral part of education. Wright’s design was never built, but it sheds light on “his own philosophy around education and the sense that architecture can stimulate the imagination of the child,” Wilson said. She also noted that in his letters, Wright, as a product of his time, often described African American culture and aesthetic sensibilities in somewhat derogatory terms. “School should be a happy place—even for the negro [sic],” he wrote in a 1928 letter about the Rosenwald project.

Another section examines the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, a massive building with integrated gardens that famously survived the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, but was demolished in 1967-68. The centerpiece of this section is Wright’s copy of a rare illustrated book on the hotel project, annotated with sketches that provide a singular look at how the Imperial Hotel originally appeared. Also included are a dozen of the archive’s nearly 1,100 drawings of the hotel, along with furniture, textiles and tableware. Together, they demonstrate the attention Wright paid to every aspect of a design in an attempt to create a cohesive work of art.

Other sections focus on Wright’s use of ornament, his little-known model of an experimental farm, his interest in Native American culture and his use of the circle to shape perceptions of the landscape.

Bergdoll, whose section reframes Wright’s proposal for a mile-high skyscraper as a bid to increase the architect’s star wattage, said: “The exhibition communicates very clearly that the archives are here now in New York at a major research university, and that they are accessible for new generations of research on Wright and American architecture, modernism and urbanism. There are facets of Wright’s career that are so relevant to issues that concern us today.”

Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive is on view at the Museum of Modern Art through Oct. 1.