Colossal Statues From an Ancient Sardinian Culture Come to Light

A new book, co-edited by Barbara Faedda, focuses on the giant figures of Mont’e Prama.

Thousands of shattered limestone pieces, dating from about 900-750 BCE, came to light in 1974 at the Mont’e Prama site in western Sardinia. They have been reassembled into dozens of colossal statues, which reward close study by archaeologists, historians, conservators, and restorers. The statues and the individual tombs in this monumental necropolis—sculpted by a powerful Mediterranean civilization—make Mont’e Prama a rich representation of a Bronze Age and Iron Age culture.

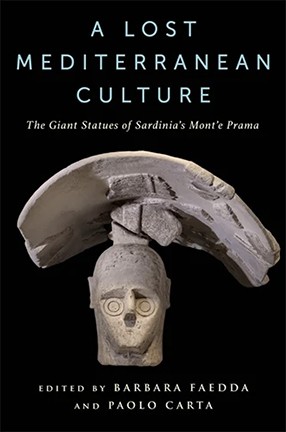

A Lost Mediterranean Culture, co-edited by Barbara Faedda, executive director of the Italian Academy and adjunct professor in the Italian Department, and Paolo Carta, a professor at the University of Trento, is the first English-language book to explore Mont’e Prama’s giant statues. They are among the most important archaeological discoveries of the past 50 years and the source of fresh discoveries even today. The book, written by the leading excavators and restorers of Monte’e Prama, recounts the history of scholarship on the artifacts, and describes the landscape, the context, and the restoration efforts. Also addressed is the illicit trafficking of Sardinian cultural property.

Faedda shares her insights on the book and Mont’e Prama with Columbia News, as well as how one of the statues came to be exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

What is this book’s back story?

Under the umbrella of the Italian Academy’s International Observatory for Cultural Heritage (which I conceived in 2016, and which has grown swiftly since then) is the Sardinia Cultural Heritage Project, supported by a $300,000 grant from Italy’s Autonomous Region of Sardinia. The aim of this multiyear initiative is to focus on the remarkable treasures of Sardinian culture, and introduce audiences to the island’s importance in Mediterranean history. I have had the pleasure of working on this book with Professor Paolo Carta of the University of Trento, who was a fellow at the Italian Academy several years ago. (It’s great when cultural and scientific collaborations arise while a fellow is in residence here, and then flourish over the years.)

In the spring of 2022, to inaugurate the Sardinia Project, we launched an online exhibition on the Mont’e Prama statues. We pivoted to this web format when our original in-person conference on the statues was disrupted by the pandemic. To our surprise and delight, the digital exhibition immediately generated enormous interest: We got 2,500 likes on Facebook in the first week alone, and 8,600 visits so far. This proved that the topic was appealing, so we geared up and produced this illustrated book of essays. We are honored to have chapters written by our contributors—Raimondo Zucca, Emerenziana Usai, Peter van Dommelen, Alfonso Stiglitz, Roberto Nardi, Guido Clemente, and Giuditta Giardini. They are among the most distinguished scholars in the field. This volume is my second collaboration with Columbia University Press, and I couldn't be more grateful—it has been such an enjoyable experience.

What is it about the Mont'e Prama statues that make them so distinctive, and different from other massive statues like, for example, the Easter Island moais?

Mont’e Prama’s figures are distinctive because they bring fresh new information about the distant past, and because of how they look. The extraordinary discovery of the Giants (as they’re known) suddenly opened doors to a period of Mediterranean prehistory that was mostly unknown. These 3,000-year-old monumental statues—depicting warriors, archers, and boxers—adorned the tombs of youths in a complex necropolis, which was used over several centuries. Since the accidental unearthing of this archaeological site in 1974, around 125 graves have been identified; about half of them have yet to be excavated.

The statues are not as tall as those on Easter Island (which average about 13 feet in height), but they are enormous and about seven feet tall. As you can see from the photo on the book’s cover, their faces are mesmerizing, with unique features that are instantly recognizable: The flat triangular face has large double-circled eyes, a thin incised mouth, and a squared-off chin.

How did the loan of one of the Mont’e Prama statues to the Metropolitan Museum happen?

After our collaboration with the Mont’e Prama Foundation was underway (as we developed the online exhibition), Anthony Muroni, the foundation’s president asked, “Barbara, shall we bring our Giant to the U.S.?” He had already exhibited one of the statues in museums in Berlin, St. Petersburg, and Thessaloniki, and he saw the U.S. as a key venue. I agreed and presented a proposal to Seán Hemingway, John A. and Carole O. Moran Curator in Charge of the Met’s Department of Greek and Roman Art.

When I brought my dossier to him, I caught a flicker of curiosity in his eyes: The statues sparked his researcher’s excitement, despite his predictable caution. The museum’s evaluation process is, of course, punctilious and highly selective. But the proposal sailed right through, and the Giant arrived in May at the Met, where it has been installed at the entrance to the museum’s Greek and Roman galleries. It will remain on view there until December 6, 2023.

The Met’s interest confirms that, as scholars have long argued, Sardinia’s ancient society deserves recognition alongside other important cultures of antiquity.

What books have you read lately that you would recommend, and why?

On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century by Timothy Snyder—timely reflections for all of us right now.

What's next on your reading list?

We Should All Be Feminists by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. I read it when my daughter was a child, and I would like to read it again, with her, now that she is a young woman.

Any exciting summer plans?

Spending time in Italy in summer is always thrilling for me and my family, even though we do it yearly. We will, of course, be in Sardinia for a couple of weeks; I am scheduled to present our Giants book at the 2023 Archaeological Literature Festival. As always, I'm going to take the opportunity to work on the Italian Academy’s upcoming initiatives while I am on the island: Sardinia has so many riches that it’s hard to choose.

I’ll also go to Rome and Paris. So my summer will be a full immersion in culture. The fact that even my vacation is so tightly tied to my work at Columbia makes my job special. The travel also gives me new energy and fresh ideas for when I resume teaching in September: One of my greatest joys is to share my cultural enthusiasm and stimulation with students here.

Which three scholars/academics, dead or alive, would you invite to a dinner party, and why?

I would invite Lorenzo Da Ponte—Mozart’s librettist, who was also Columbia's first professor of Italian—and his two friends: the writer and scholar Clement Clarke Moore (famous for the poem “’Twas the Night Before Christmas”) and the author and publisher William Cullen Bryant. I would love to hear from them about the cultural and political scene in New York in their time, the 19th century, as I am deeply interested in that period, especially the relationship between Italian and American culture in the 1800s. I’d like to get back to my research and writing on that era.