How Can You Separate Fact From Fiction in the News?

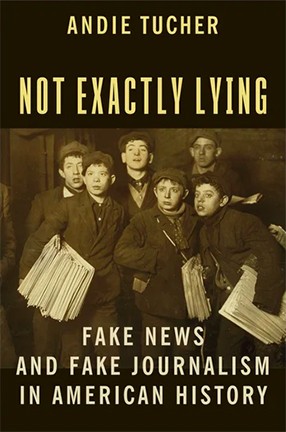

Journalism Professor Andie Tucher explains the differences in her new book, “Not Exactly Lying.”

Long before the current preoccupation with fake news, American newspapers routinely ran stories that were not quite, strictly speaking, true. Today, a firm boundary between fact and fakery is a hallmark of journalistic practice, yet for many readers and publishers across more than three centuries, this distinction has seemed slippery or even irrelevant.

From fibs about royal incest in America’s first newspaper to social-media-driven conspiracy theories surrounding Barack Obama’s birthplace, Andie Tucher, the H. Gordon Garbedian Professor of Journalism, explores how American audiences have argued over what’s real and what’s not—and why that matters for democracy—in Not Exactly Lying: Fake News and Fake Journalism in American History.

Columbia News caught up with Tucher recently to find out more about the book, as well as which books she’s read recently and which she’s turning to next, and what some of her students tell her at the end of her journalism history survey course.

Q. Why did you write this book?

A. I’ve actually been writing this book for most of my life. I learned early on in my career as a historian of journalism that it’s pointless to study the conventions of truth-telling without also acknowledging the many ways—and the many reasons, from the demagogic to the mischievous to the cynical—that those conventions have been exploited. The fakery and manipulation we’ve been seeing lately in public life are vast in scale and deeply disturbing, but they’re not new.

Q. What do you think is the main threat to democracy and public life if what passes for news is not exactly true? And how can one possibly create objective content?

A. A big challenge is that “objectivity” means so many different things to different people, and arguments that purport to be about journalistic principles are actually about who will own the truth. Many of the news organizations devoted to opinion—most, though not all, on the right—insist that the news they present is the only kind that is fair, balanced, unbiased, and true.

At the same time, more and more mainstream news organizations, sometimes under pressure from passionate readers impatient with traditional objectivity, are acknowledging and even embracing their own subjectivity. This gives us a situation in which the opinionated side can argue “that’s just your opinion, we have the facts,” while the other side can only reply “it’s our opinion that those facts are wrong.” The debate is rigged!

Q. What books have you read lately that you would recommend, and why?

A. I’ve been rereading some of the works by my friend and colleague Todd Gitlin, who died in February, and whose provocative but sane voice on practical politics and social change I deeply miss.

Q. What's next on your reading list?

A. I’m interested in Jacob Mchangama’s huge and imposing Free Speech: A History from Socrates to Social Media, and Jing Tsu’s Kingdom of Characters: The Language Revolution That Made China Modern. In the department of guilty pleasures, Mick Herron’s Bad Actors, the eighth installment in his sly and ingenious Slough House spy series.

Q. What are you teaching this semester?

A. Two of my favorites: a survey of journalism history, required for all students in the professional journalism MS program (there are always a few students who tell me at the end of the course that “I never thought history was interesting before!”), and an undergraduate course called Journalism and Public Life, where I get to debate the Big Issues with really smart young people who may yet figure out how to fix journalism.

Q. You're hosting a dinner party. Which three academics or scholars, dead or alive, would you invite, and why?

A. Herodotus, the “father of history”—though he may not have been the most reliable of fathers, he was a crack storyteller.

MIT Professor Sherry Turkle, crafter of such a rich and unconventional multidisciplinary life that she could fill a dinner table all by herself.

Princeton Professor Emeritus Robert Hollander, whose brilliant course, European Literature: Reason and Folly, which I took as a sophomore, was my introduction to the sheer thrill of ideas. (On the first day, he said, “Pay no attention to the course title; I needed something for the catalogue. These are just my favorite books.”)

Check out Books to learn more about publications by Columbia professors.