If You’re Mad About Music and Marie Antoinette, Read This Book

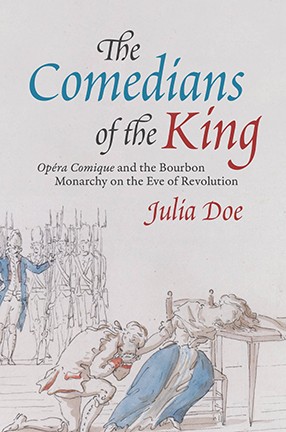

In “The Comedians of the King,” Professor Julia Doe explores opéra comique and the Bourbon monarchy on the eve of the French Revolution.

Lyric theater in ancien régime France was a political art, tied to the demands of court spectacle. This was true not only of tragic opera (tragédie lyrique), but also its comic counterpart, opéra comique, a form tracing its roots to the seasonal trade fairs of Paris. While historians have long privileged the genre’s popular origins, opéra comique was brought under the protection of the French crown in 1762, thus consolidating a new venue where national music might be debated and defined.

In her new book, The Comedians of the King, Julia Doe, professor of music, traces the impact of Bourbon patronage on the development of opéra comique in the turbulent pre-revolutionary years. Drawing on both musical and archival evidence, the book presents the history of this understudied genre and unpacks the material structures that supported its rapid evolution. Doe demonstrates how comic theater was exploited in, and worked against, the monarchy’s carefully cultivated public image—a negotiation that became especially fraught after the accession of the music-loving queen, Marie Antoinette.

Doe shared her thoughts on the book with Columbia News, along with what events she’s anticipating in New York’s fall cultural season, what she’s teaching, and what it might have been like to hear the 10-year-old Mozart play the keyboard at an 18th-century Parisian salon.

Q. Why did you write this book?

A. I’m a cultural historian, and my research examines the ways that opera shapes and is shaped by politics. There are few musical repertories more rewarding for this type of study than those produced in pre-revolutionary France. The political implications of tragédie lyrique in this period are fairly self-evident. Grand, heroic, and spectacular, the genre originated under the auspices of Louis XIV and transparently allegorized the achievements of the monarchy. (One musicologist has cheekily described such works as the “courtliest court operas” ever written.)

I was curious, however, to explore the meanings inherent in tragédie lyrique’s long-neglected comic counterpart, opéra comique. The latter genre has a reputation for being popularly inflected and politically subversive; it originated at the suburban fairs of Paris, and incorporated the progressive ideals of the philosophes. But over the course of the 18th century, opéra comique also became a favorite of the French aristocracy and was increasingly showcased at Versailles.

My book explores the tensions that arose as this ostensibly “lowbrow” musical form was appropriated as an emblematic courtly art. It turns out that comic theater might also serve absolutist political ends, but not without complications for the crown.

Q. How does Marie Antoinette fit into this story?

A. Marie Antoinette’s musical pursuits have attracted less scholarly attention than her other artistic activities, but she was remarkably active as a performer and patron. She supported composers like Christoph Willibald Gluck and Niccolò Piccinni, frequently attended concerts in Paris, and took regular lessons in voice and in harp. When she gave birth to her children, she even had a temporary stage constructed in her private apartments, so that opera could continue unabated as she convalesced!

My research in the archives of the French royal household indicates that the queen’s musical preferences were impressively forward-looking. She forcefully advocated for opéra comique and Italianate comedy at a time when those genres stood in antithesis to the courtly status quo. But not everyone was pleased when the monarch transformed the conservative theaters of Versailles into bastions of musical modernity. For opponents of the regime, Marie Antoinette’s newfangled operatic tastes marked an affront to dramatic, and by extension, to social propriety; this was interpreted as improper conduct from a “frivolous,” foreign-born queen.

Q. What are you most looking forward to about New York’s fall cultural season in terms of music and theater? Will you be attending any live events?

A. As a professional opera scholar—and all-around music lover—I am thrilled that we’ll once again be able to attend live performances this fall. I’m looking forward to the Metropolitan Opera’s reopening. I’ll also continue to support smaller, New York-based opera companies—like Heartbeat Opera and Onsite Opera—that have creatively adapted to the exigencies of the pandemic. Closer to “home,” we can’t yet attend in-person events at Miller Theatre, but this venue has an exciting line-up of streaming concerts in the next few months as well.

Q. What are you teaching this semester?

A. I’m on a research leave this semester to do some archival work that was delayed during the pandemic. In the spring, I’ll be teaching one of my favorite classes, “Paris for Romantics,” an undergraduate seminar that traces the city’s 19th-century history through its music. So many influential artists lived in, passed through, or were inspired by the French capital in these years. Students gain a deeper understanding of well-known figures like Frédéric Chopin and Claude Debussy, as well as an introduction to some composers they might not have previously encountered. (A personal favorite is Louise Farrenc, the first woman to be named professor of piano at the Paris Conservatoire, and author of some wonderful chamber music.)

Throughout, we use musical repertory as a lens through which to examine France’s social and political development. At the beginning of the term, we explore the sonic echoes of the French and Haitian revolutions; near the end, we interrogate the rise of musical nationalism after the Franco-Prussian War. The class draws students from a variety of majors, and it’s rewarding to show them how music might function as historical evidence, giving us a rich perspective of the society that created it.

Q. You're hosting a dinner party. Which three scholars or academics, dead or alive, would you invite, and why?

A. I’m going to do something I wouldn’t always encourage in the classroom and answer a different but related question! My “Music Humanities” students know I occasionally engage in this sort of thought experiment with historical concerts. What artists from the core curriculum would I have loved to hear play? (Clara Schumann, perhaps.) What scandalous musical premieres would I have liked to have attended? (A top contender here is Igor Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring.)

More pertinent to my research, I’m currently working on a project about domestic and sociable music-making in 18th-century France. So I’ve been thinking a lot about one of the most famous images of an Enlightenment salon, Michel Barthélemy Ollivier’s Le thé à l’anglais from the mid-1760s. The painting depicts a host of artistic notables and philosophes being treated to—and largely ignoring—a keyboard performance from the 10-year-old Mozart. (The composer visited Paris on his childhood tours through Europe.) Historians continue to debate many aspects of salon practice: How serious were the discussions that took place in these venues? How was music incorporated alongside other entertainments? I’d learn a lot by teleporting myself into the scene that Ollivier captured. Hearing Mozart live wouldn’t be bad either!

Check out Books to learn more about publications by Columbia professors.