How Can Cities Help the Climate Crisis?

By replicating successful strategies found in nature, as Dickson Despommier outlines in his new book.

Cities are core drivers of the climate crisis, as Dickson Despommier, an emeritus professor of public health and microbiology at Columbia, details in The New City: How to Build Our Sustainable Urban Future. Cities’ dependence on the outside world for vital resources is causing global temperatures to rise and wildlife habitats to shrink. But there is an opportunity, says Despommier, to make cities more sustainable by transforming the built environment.

In the book, he proposes a visionary yet achievable plan for creating a new, self-sustaining urban landscape. He argues for solutions based on the concept of biomimicry—emulating successful strategies found in nature. A better city is possible if its design echoes the ways in which forests and trees store carbon, grow food, collect rainwater, and convert sunlight into energy. By describing established and leading-edge technologies, The New City provides a blueprint for this new urban environment.

Cities built from wood are more resilient and less destructive than concrete and steel construction; they also encourage reforestation, boosting carbon sequestration. Vertical farms inside city limits supply residents with a reliable, healthy food supply. Buildings will harvest moisture from the rain and air to secure a clean water supply. Renewable energy—including not only wind, solar, and geothermal, but also clear, photovoltaic window glass and nonpolluting hydrogen fuel cells—can power a cleaner city.

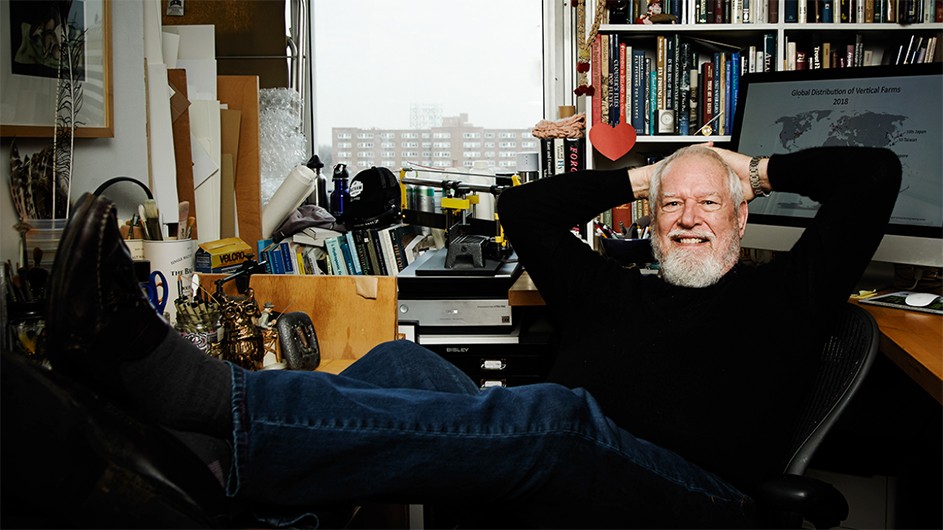

Despommier discusses the book with Columbia News, along with how he keeps busy and what books he’s read lately.

How did this book come about?

I have always been passionate about issues that threaten our environment. I grew up in post-WWII suburban California, in the Bay Area, and witnessed firsthand the power of developers who moved in and rearranged the natural portion of my playground. They bulldozed the wild open fields around my town, San Lorenzo, and turned them into tract housing projects. In 1951, my family moved to Dumont, New Jersey, and settled into another version of what I had just experienced. As soon as I learned how to catch trout on my own at age 14, the rivers I fished in began to show signs of nearby urbanization. Most of the local streams within my range of bicycling—which, at one point, held wild populations of brook trout—were now heavily impacted by a growing suburban population. The brook trout were nowhere to be found, as local residents had eaten them. There were the occasional stockies that the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection managed to put in some of the rivers, but when summer rolled around, all the fish had either been caught or succumbed due to high water temperatures.

The Garden State was—and still is—guilty of misrepresenting the untouched trout habitat that can still be found in a few out-of-the-way places. Trout Unlimited, a national conservation organization, refused to designate any New Jersey river as acceptable, since there were no catch-and-release fishing areas. New Jersey river management was strictly a catch-clean-and-cook proposition. So I began looking for other rivers in adjacent New York State, where I still fish occasionally.

Fast forward to the present. I am now 83 years young, with the advantage of hindsight. Several years ago, I was diagnosed with bladder cancer—a game-changer, for sure. I sought out the best medical care I could find, and I began focusing on the things that give me the most pleasure, and offer me the best opportunity to share my knowledge with the public. I resigned from my adjunct teaching position at Fordham University, and began writing about the environment. The theme of a Fordham project I had directed, Fordhamopolis, showed how to improve our urban environment while, at the same time, enabling the rewilding of what remains a fragmented natural world. The result is The New City.

Can you give some examples from the book of how urban design can successfully embrace biomimicry?

The principles described in my book are straightforward and rather simple. Look to nature for answers that could be applied to solving rapid climate change. In doing so, we might also be able to revitalize some of the ecosystems we have damaged. I begin The New City by describing some of the major issues that caused this disruption of natural systems, resulting in a rise in the average global temperature. In creating a new city, my Fordham class and I explored many viable options and settled on those that least harm the natural world. Four pillars serve as the premise for urban change.

The first change is to switch from steel and concrete for building materials to an engineered wood product—cross-laminated timber known as CLT—with characteristics similar to those found in mature trees. CLT has twice the strength of steel, is twice as light, and can be recycled and used for a new building. It is more fire-retardant than conventional construction materials, and, unlike any of those, it sequesters carbon, since it is made from wood. The trees CLT is made from will grow back in about 20 years, a renewable resource that will become available for manufacturing more CLT. Creating an abundance of trees to supply CLT manufacturers enables the restoration of damaged forests, particularly temperate-zone forests.

The second pillar is adding vertical farms to every building in the new urban environment. Cities occupy less than 3% of the world’s land mass, but generate over 60% of the greenhouse gases responsible for rapid climate change. Since 50% of the world population now lives in cities, urban environments must learn how to feed themselves (another function of trees), thereby helping to re-establish balanced ecosystems.

The third pillar—water harvesting. Water is essential for all life on earth. The anthropogenic world has had little interest in conserving fresh water until recently. Buildings should be designed to capture every drop of rainwater on their surface (just like trees do). Bermuda already does this. An example will show how more urban areas need to do so. New York City has a little over 300 square miles of physical footprint. Its average annual rainfall is about 47 inches. This might not seem like a lot of water to the casual observer, but a simple calculation suggests otherwise. The total amount of water that falls on New York annually is an astounding 240 billion gallons. This city consumes over 500 billion gallons a year to quench the thirst of its 8 million inhabitants. So New York could offset its freshwater demand by 20-30% if it were to retrofit its buildings to enable each one to capture rainwater. Moreover, the city discards some 1.2 billion gallons of wastewater daily. Remediating this water to become drinkable would alleviate future water shortages.

The final pillar: Converting cities from using fossil fuels to renewable energy resources, including solar, wind, and geothermal sources. On the near horizon, hydrogen fuel cell technologies will likely replace all energy-generating schemes. Why? Hydrogen fuel technologies do not generate harmful waste. The by-product of this approach’s energy production is water.

Are there cities that are employing these sustainable solutions?

Many cities are currently trying new approaches for all four pillars, and I reference them throughout the text.

Do you miss teaching?

Of course! Writing books is one way of continuing my passion for teaching. I love exposing students to new ideas, and then letting them run with those ideas. The outcomes are always surprising and rewarding. We who teach at times give students too little credit for self-motivation. Allowing them to take charge of an idea is empowering and life-changing, both for them and for us!

How do you remain active in your field?

I am a member of a podcasting crew headed by Vincent Racaniello, the Higgins Professor of Microbiology and Immunology at Columbia. I co-host two shows, This Week in Virology and This Week in Parasitism. I give several lectures yearly to various classes at the Mailman School of Public Health. I also co-founded Parasites Without Borders, and remain active with its projects. And I continue to do outreach and presentations to schools.

What books have you read lately that you would recommend, and why?

I must confess that writing a book consumes a lot of time, so my recreational reading has suffered a bit. My passion for trout fishing always leads me to fishing-related books. Anything written by Roderick Haig-Brown, a Canadian writer and conservationist who died in 1976, gets my attention. His writing goes far beyond the look-what-I-caught stage. I often pick up Fisherman’s Winter, one of his best books, and read from it. His observations of nature are exquisitely expressed, and he paints vivid mental images of the places he visited.

Of course, you cannot write a book about something as complex as rapid climate change without reading seminal works by experts. Here are some:

Hubbard Brook: The Story of a Forest Ecosystem by Richard Holmes and Gene Likens details how a mixed boreal forest in New Hampshire behaved after a catastrophic clearcut experience that Likens initiated in 1967. He and his colleagues then studied how the forest he tried to destroy recovered independently. Likens continues to study the Hubbard Brook Forest, using it as his laboratory. The project is the longest continuous ecological study in the world.

Finding the Mother Tree by Suzanne Simard delivers passionate prose about how nature works. The subtext is that almost no forestry scientists believed her results until a corps of young forest ecologists replicated them in their own forest patches. Using radioactive tracer metabolites, her influential discovery was that older trees "talk" to each other via chemical signaling pathways. This is how a city and its buildings should behave, and we have the technologies to make that happen.

The Overstory by Richard Powers is a novel with lots of science about forests and their survival, mixed into a riveting series of seemingly unrelated stories that all come together in the end.

What's next on your reading list?

My next book.