Tracing Dan-el Padilla Peralta's Journey from Homeless to the Ivy League

Dan-el Padilla Peralta feels an unusual connection to the former prisoners he taught this summer as part of Columbia’s Justice-in-Education initiative. He knows what it is like to feel “condemned to the periphery of American society,” he says. A lecturer in the Classics Department and a member of Columbia’s Society of Fellows, Padilla, born in the Dominican Republic, grew up in New York City as an undocumented immigrant. “It shut so many doors,” he says. “I could be deported at any time.”

He was four years old when his parents brought him to New York so his mother, then pregnant with his younger brother, could get medical care for diabetes. When their tourist visa expired, his parents paid a private immigration service to get an extension but never heard more. His father, an accountant, couldn’t find steady work and returned to Santo Domingo. His mother stayed, hoping to provide a better life for her sons.

Their story is one of luck and determination. They lived in apartments in Harlem while their mother, a pension-fund director in the Dominican Republic, worked as a maid; they also spent two years in homeless shelters. Padilla was nine years old when a book about ancient Greece and Rome in a homeless shelter library sparked his interest in the classics. A young shelter volunteer later helped him apply to Collegiate School, an elite private school in Manhattan. He was accepted with a full scholarship; no one asked about his immigration status.

Padilla went on to earn a B.A. from Princeton, an M. Phil. from Oxford and a Ph.D. from Stanford. His brother Yando graduated from Bowdoin, and is entering his second year at Fordham Law School.

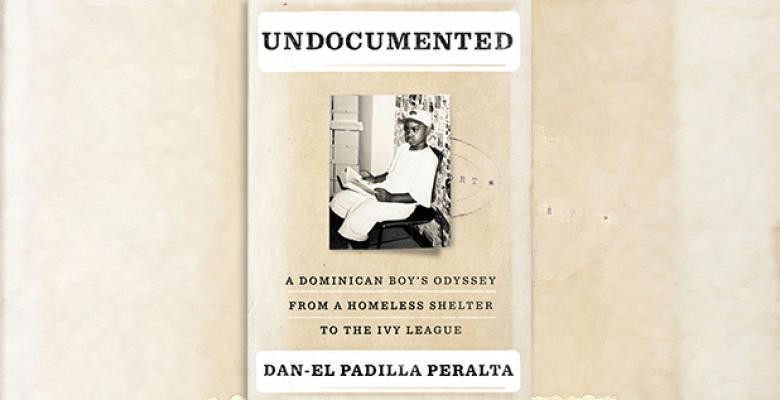

He has written of his unconventional journey in a memoir, Undocumented: A Dominican Boy’s Odyssey from a Homeless Shelter to the Ivy League, published by Penguin Press in July. At the beginning is a quote from Sen. Jeff Sessions (R. Ala.), “Fundamentally, almost no one coming from the Dominican Republic to the United States is coming because they have a skill that would benefit us and that would indicate their likely success in our society,” Sessions said on the Senate floor in 2006.

This summer, Padilla taught a course to former prisoners based on the Core Curriculum required of all Columbia undergraduates, with readings from Homer, Plato and Aristotle, Shakespeare, W.E.B. DuBois and Tayeb Salih. “It’s about helping them develop the skills needed to understand these texts,” said Padilla, who taught a section of the Core to sophomores last fall. The former prisoners who completed the summer class earned four credits and plan to continue their education at various schools in New York.

Padilla was salutatorian of his graduating class at Princeton in 2006 and gave the traditional Commencement address in Latin. He also won a prestigious fellowship to Oxford University, but as an undocumented immigrant, he didn’t think he could go; if he left the U.S. he couldn’t return for 10 years. With Princeton’s help, and money he raised to pay a lawyer, Padilla obtained a work visa to be a Princeton research assistant during vacations from Oxford.

Padilla, who will turn 31 in September, came to Columbia last fall. He is working on a second book, Divine Institutions: Religion and State Formation in Republican Rome, a revision of his Ph.D. thesis scheduled for publication in 2017.

“He is an extraordinarily talented and devoted teacher and just about the best role model one could imagine,” says Eileen Gillooly, executive director of the Heyman Center, who asked him to teach the summer course. She notes that Padilla was the top choice among more than 1,000 applicants for the Columbia fellowship. He currently has a student visa. In March he married his longtime girlfriend, a New Jersey native, and has applied for a green card, the first step on the path to U.S. citizenship.

His memoir ends with a reflection on what it means to be an undocumented immigrant. “As much as I love America, I’m angry with it, too,” he writes. “Every single day, the ambitions and aptitudes of the undocumented millions are trivialized and marginalized by an immigration policy lacking in rationality and justice… My hope for this book is that it will communicate a sense of their potential contribution.”