'Over the Rainbow': The Story Behind the Song of the Century

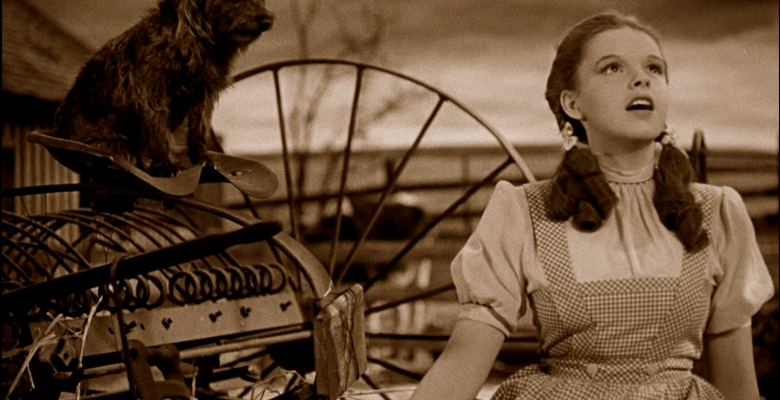

When Judy Garland went over the rainbow as Dorothy Gale in the classic 1939 musical The Wizard of Oz, she almost left without singing what was to become her signature number. For an advance screening, MGM executives had removed “Over the Rainbow” because they felt it slowed down the film.

Associate producer Arthur Freed stepped in, telling studio head Louis B. Mayer, “The song stays—or I go,” to which Mayer replied: “Let the boys have the damn song. Put it back in the picture. It can’t hurt.” More than 75 years later, the film and the song by composer Harold Arlen and lyricist Yip Harburg are cultural touchstones. In 2001, “Over the Rainbow” was voted the greatest song of the 20th century in a joint survey by the National Endowment for the Arts and the Recording Industry Association of America.

“It might not seem obvious that a song performed by a young girl at the beginning of a fantasy movie would take on a life of its own,” said Walter Frisch, a professor of music whose new book, Arlen and Harburg’s Over the Rainbow, traces the work’s history. One factor of the song’s appeal that Frisch cites is the universality of a childhood desire to get away or escape. “The song’s mix of hope and anxiety has allowed people to read into it their own concerns,” he said, noting that the lyrics are general enough that one would not know the singer was standing in a farmyard with her dog.

Frisch defines “Over the Rainbow” as a classic “I want” song, delivered at the outset of a show or film to “express the desires that will motivate the protagonist’s actions.” Freed wanted a ballad that would rival a popular film song of the time, “Someday My Prince Will Come” from Walt Disney’s 1937 animated hit Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

“When I tell people that I’m working on Harold Arlen’s music, they sort of stare at me blankly, not recognizing his name,” Frisch said. “But when I mention ‘Over the Rainbow’ and ‘Stormy Weather,’ they say, ‘He did those?’” Frisch believes that the composer’s name should be as well known as his contemporaries George Gershwin or Irving Berlin.

Arlen’s music covers a wide range of styles, from jazz-inspired tunes to light-hearted patter. As they collaborated, Harburg would generally suggest an idea or title connected with the plot, Arlen would compose the music, and then Harburg would write the lyrics. Musical inspiration often struck at odd moments. On his way to Grauman’s Chinese Theatre with his wife, Arlen asked her to stop the car as they passed Schwab’s drugstore on Sunset Boulevard. In a burst of creativity, he jotted down the tune for “Over the Rainbow” on the music paper that he invariably carried with him.

An Arlen trademark is to begin a song with an octave leap, as in the opening syllables’ “Some-WHERE.” The section “Someday I’ll wish upon a star” was meant to imitate a child’s piano exercise, Arlen claimed. Harburg recalled that it was the way Arlen whistled to call his dog. When Harburg and Arlen were stuck on an ending for the song, Ira Gershwin stepped in to help. When asked why he suggested ending the song with the question, “Why, oh, why can’t I,” Gershwin later recalled, “Well, it was getting to be a long evening.”

The song that Garland later called “sacred” became her anthem. When it was named song of the century, the headlines were usually along the lines of “Judy Garland’s ‘Over the Rainbow’ is No. 1,” with hardly a mention of the composer or lyricist. The song followed and sometimes burdened her throughout the decades. “It’s like being a grandmother in pigtails,” she once said.

Garland would interpret “Over the Rainbow” differently by changing its “tempo, timbre, rhythm, phrasing, diction and choice of pitches,” Frisch writes, noting that: “It grew with her and became the culminating moment of her concerts. At her Carnegie Hall concert in 1961, everyone knew that she was going to sing it, but the audience would have to clamor for it.”

Frisch’s main area of research has been Austro-German music from the 1820s to the 1930s. “People ask me, ‘How do you get from Brahms to Harold Arlen?’” he said. “For me, what is special about both Brahms and Arlen is that they are deeply expressive, yet there is always a sense that the emotion is being controlled, which imparts yearning and longing.”

He doubts that there is “one real authentic” version of “Over the Rainbow.” “There are as many different versions as there are performers and contexts,” he said. Just this year in Manchester, England, Ariana Grande sang it as an encore at a benefit concert for the victims of a bombing at one of her earlier concerts. “Here the song conveyed a message of solidarity and reassurance,” Frisch said.

Scores of famous singers have recorded versions of the song over its long and rich life. Frisch ends his book by honoring its creators with an allusion to a scene near the conclusion of The Wizard of Oz: “We should give credit to the men behind the curtain. Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg are the real-life wizards.”