The Associated Press in Nazi Germany

Co-writer Ann Cooper’s Newshawks in Berlin describes the perils of reporting from war zones.

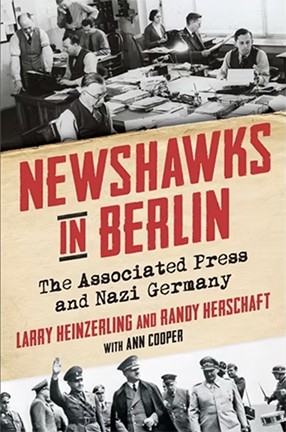

After the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933, the Associated Press (AP) brought news about life under the Third Reich to millions of American readers. The AP was America’s most important source for foreign news, but to continue reporting under the Nazi regime, the agency made compromises. Its reporters and photographers in Berlin endured censorship, complied with antisemitic edicts, and faced accusations of spreading pro-Nazi propaganda. Yet, despite restrictions, pressures, and concessions, AP’s Berlin journalists provided more than a thousand U.S. newspapers with extensive coverage of the Nazi campaigns to conquer Europe and annihilate the continent’s Jews, as the book Newshawks in Berlin, by Larry Heinzerling, Randy Herschaft, and Ann Cooper, a professor emeritus at Columbia Journalism School, shows.

Newshawks in Berlin reveals how the AP covered Nazi Germany from its earliest days through the aftermath of World War II. Heinzerling and Herschaft accessed previously classified government documents; plumbed diary entries, letters, and memos; and reviewed thousands of published stories and photos to examine what the AP reported, and what it left out. Their research both uncovers fierce internal debates about how to report in a dictatorship, and reveals decisions that sometimes prioritized business ambitions over journalistic ethics. The book also documents AP’s coverage of the Holocaust and its unveiling.

Columbia News recently caught up with Ann Cooper to discuss the book, as well as books she’s currently immersed in, and which journalists she would invite to a dinner party.

How did you become involved in the writing of this book?

In 2016, the Associated Press was stunned when a German historian published a report claiming that AP had ceded influence to Nazi propagandists over the work of AP’s German-registered photo service. The report said AP photos were used in antisemitic Nazi publications, and that some of AP’s German photographers served in Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS propaganda companies while also on AP’s payroll.

This was news to the managers in charge of AP in 2016—and to my husband, Larry Heinzerling, who had been AP’s bureau chief in Germany in the 1980s. AP asked Larry to investigate, and along with his colleague Randy Herschaft, he produced a 2017 report with details of the very compromised photo operation.

Larry and Randy also realized there was much more to the story of how AP operated in Nazi Germany, where it had both a photo service and a news bureau staffed by half a dozen foreign correspondents. They worked for several more years, independent of AP, to produce a manuscript that looked broadly at how the wire service functioned in Nazi Germany. I read and commented on that manuscript as it was produced. When Larry died of cancer in 2021, I continued working with Randy to revise and refine the work that Columbia University Press published as Newshawks in Berlin.

Can you provide some examples from the book of the compromises AP reporters made while working in 1930s Nazi Germany?

The most questionable actions involved AP photo operations, which continued to function throughout the war exchanging photos under the auspices of the Nazi Foreign Ministry—including using German diplomatic pouches to get photos in and out of the country, at a time when the U.S. and Germany were at war with each other.

Besides the photo service, AP had a robust bureau of correspondents whose stories were distributed every day to some 1,200 U.S. newspapers. As Nazi restrictions on reporting tightened, all the foreign news bureaus in Berlin practiced self-censorship to some degree to avoid expulsion. But AP was often more cautious than its competitors. The wire service’s longtime Berlin bureau chief, Louis Lochner, argued that it was vital for AP to avoid expulsion because so much of American media relied on its reports. Despite the restrictions and Lochner’s cautious approach, AP’s coverage of Nazi Germany was remarkably comprehensive, including on the crucial story of the fate of Europe’s Jews.

What are some lessons from the book that can be applied to journalists today who are reporting on authoritarian regimes?

I think it’s useful to read about the debate journalists face in dictatorships: Whether to stay and report within the confines of censorship, or to leave and lose your ability to report first-hand. Thanks to the internet and social media, today’s journalists can do more reporting from exile than the Berlin newshawks could if they had decided to leave Germany. But there is still no consensus on the stay or go dilemma; most reporters see an advantage to being on the ground, even if they can’t report everything they see.

It’s also illuminating to see how critics sometimes attacked AP reporters who accepted trips to European battlefronts under Nazi escort. We hear the same sort of criticisms today when journalists travel with one side or the other in conflict zones. I was struck with a comment made last year by Mary Louise Kelly of NPR, after she was criticized for visiting Iran under official escort: There is no substitute, she said, “for being on the ground, seeing what you can see, knowing at the same time that it’s the narrowest slice, and that you’re only seeing a tiny bit of a huge and vast and complex country.” As with the Berlin newshawks, the key to such trips is to be transparent with readers, to describe what restrictions and rules applied, and then to use the opportunity to see and report as much as possible.

What have you read lately that you would recommend, and why?

I have been immersed in two great novels by Andriy Kurkov: Death and the Penguin, whose dark humor explores absurdities of post-Soviet life, and Grey Bees, a bleak, gripping tale of life in the gray zone between loyalist and separatist forces in Ukraine’s Donbas region. It was great to hear from Kurkov in person last fall, when he was writer in residence at Columbia's Harriman Institute. From him, we learned the devastating impact that Russia’s full-scale invasion has had on Ukrainian literature.

What's next on your reading list?

The Murder of Nikolai Vavilov: The Story of Stalin’s Persecution of One of the Great Scientists of the Twentieth Century, by a former Moscow correspondent, Peter Pringle. I missed this book when it came out some years ago, and will gladly return to Soviet history after several years of immersion in books about the Nazi era.

Which three journalists, dead or alive, would you invite to a dinner party, and why?

Vasily Grossman, the Jewish Russian writer who covered World War II and the unveiling of the Holocaust for Soviet media; Mstyslav Chernov, AP journalist and director of 20 Days in Mariupol, the film based on his remarkable reporting from that Ukrainian city under Russian siege; and Lindsey Hilsum, international editor at UK’s Channel 4, who has covered conflicts and refugee crises around the globe for 30 years. I predict an intense conversation that would illuminate the importance of telling the stories of conflict, and its impact on civilians caught in the middle.