A Book About the End of One Relationship, and the Beginning of Another

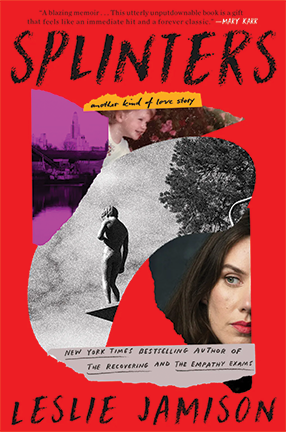

In Splinters, her first memoir, Leslie Jamison explores her divorce and the birth of her daughter.

In her first memoir, Splinters: Another Kind of Love Story, Leslie Jamison, the head of the nonfiction concentration in the Writing Program at School of the Arts, turns her powers of perception on some of the most intimate relationships of her life. In examining her love for her young daughter, her ruptured marriage, and the legacy of her parents’ complicated bond, Jamison explores what it means for a woman to be many things at once—a mother, an artist, a teacher, a lover. In a book that grieves the departure of one love even as it celebrates the arrival of another, Jamison asks: How do we move forward into joy when we are haunted by loss? How do we claim hope alongside the harm we’ve caused?

Jamison talked about the book with Columbia News, as well as what it’s like to be a mother now, the importance of reading for the craft of writing, and how she manages the overlap of teaching and writing.

What prompted your first memoir at this point in your life?

Splinters is a memoir about two major transformations in my life that happened at around the same time—the birth of my daughter and the end of my marriage. I wanted to write into the ways that their intersection filled my days with awe and grief at once. It was really that tangled double-helix of feeling that made me want to write the book. When I write, I’m always motivated by a question that feels like a thorn in my shoe, something I can’t let go of. In this case, the question emerges from daily living with my daughter: Will every moment of our happiness feel haunted by loss?

Do you think raising a child now is more fraught than it was when you were growing up?

Maybe every generation thinks this? I don’t know, having only been part of my own. But I’m wary of feeling singular in history when I’m just part of the ongoing rhythms of history. In any case, I do worry about screens—how they are so much a part of kids’ lives now in a way they weren’t when I was young—and I feel like one of my sacred duties in this life is to protect my daughter’s imagination from a screen-dominated life. To protect her moments of boredom and invention and imaginative solitude. I try to limit my daughter’s time on screens to weekends, and not to be on my own phone around her. My mother always told me, “Kids don’t do what you say, they do what you do.”

What books have you read lately that you would recommend, and why?

Two of my favorite recent books are both by recent Columbia MFA alumni (I am admittedly biased): Emmeline Clein’s Dead Weight—a collection of essays about disordered eating—and Eliza Barry Callahan’s The Hearing Test, a novel about a young woman who suddenly loses her ability to hear. She goes on long walks using Google Maps, and the whole book feels like that—a surreal fever dream, a walk through the world as an uncanny valley.

Emmeline and Eliza were both in my thesis workshop in the fall of 2020, when we were entirely online. It was an incredible class, an incredible group of students. It’s been amazing to watch them take their thesis projects and turn them into these books. The three of us are doing an event together, Crisis and Desire, at the School of the Arts’ Lenfest Center for the Arts on April 11—one of my book tour events I’m most looking forward to.

What's next on your reading list?

Exhibit, a novel by R.O. Kwon, and Brotherless Night, a novel by V.V. Ganeshananthan.

What are you working on now?

A book about daydreaming—a combination of personal narrative, cultural history, literary criticism, and psychological history—that is investigating the role fantasies play in our lives. In a way, daydreams are our deepest secrets, which, of course, makes me fascinated by them. Over the course of my research, I’ve gathered narratives from more than a hundred people about their daydreaming lives.

How important to the craft of writing is reading?

I fell in love with reading as a little girl—curled up in the corner of the couch with a sleeve of graham crackers, lost in other worlds, other lives—and that love has always fueled my writing: the feeling of transportation and company and being summoned that came from reading; I always wanted to give that to other people, if I could. It’s a bit like mothering in that sense: I’m very close to my mother, and I’ve always felt like, if I could just give my daughter even a FRACTION of the love I’ve received from my mother, it will be enough. I sometimes feel some version of that around reading, If I could just give readers some fraction of what I’ve received, in my own reading, my work is done. So that’s the inspiration part of things. But on the craft side of things, reading also feels like oxygen: It gives me ideas, it loosens me from my own ways of doing things, it spurs me to write better, sharper, truer, deeper.

For Splinters, I had a few books that I think of as godmother texts, like Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights, composed of fragments and evoking the pain of divorce with such nuance and understatement. In that book, Hardwick summons emotion not by describing it, but by looking beyond the self—at the furniture in her apartment, the streets of Manhattan, the singing of Billie Holiday. The way her gaze holds her emotion; that’s a craft lesson. Another godmother text was Deborah Levy’s The Cost of Living—about rebuilding a life after divorce, but grounded in small daily moments, buying a plant or taking a swim, glimmering with wry humor and sharp arrows of wisdom.

When I was writing Splinters, in all these moments of writing a prior version of myself that I felt angry at, or disconnected from, I thought about how James Baldwin speaks as a present-tense narrator regarding his prior selves with such compassion and respect in The Fire Next Time—that’s a call not to underestimate my former selves, to let them be multiple and irreducible. A bookshelf full of books feels like an entire flock of teachers, infinite and patient—ready to offer their lessons whenever I need them, whenever I’m ready to hear them.

How does the intersection of writing and teaching affect you?

Among other things, Splinters is absolutely a memoir about teaching—about how my students push me to think about writing in new ways, and about how showing up for them is a constant engine of meaning in my life. I couldn’t imagine my creative life without teaching. In addition to all the ways teaching is a source of meaning in my life—I find it intensely meaningful, a true honor, to nurture and mentor young writers, to witness and support the work they make—teaching also gives so much back to me. It feels so essential to the rhythms of my thinking; it keeps my own writing life feeling energized and oxygenated. These gifts aren’t the point, but I’m grateful for them. I’m a perpetual student of my students.

What are you teaching this semester?

A lecture course, The Self, focused on the craft of constructing a self on the page. We’re exploring how to create an autobiographical “I,” who feels plural (as we all do), and navigates the built worlds of prose in surprising and dynamic ways—through break-ups and bus rides and breastfeeding sessions, through the haunted hallways of memory and desire.

We’re talking about the shame that can attach to writing from personal experience, or gets projected onto this task, and the rigorous work of turning this personal experience into art. The ideas in the course feel so connected to Splinters, so it feels like the perfect course to be teaching as I put this book into the world—an exploration of why I feel this kind of work is important, and how hard it is to get it right.

Who would you invite to a literary dinner party?

James Baldwin. Saint Augustine. Deborah Levy. Sylvia Plath.