A Book Profiles an 18th-Century Indigenous Leader Still Revered Today

Samson Occom was the first Native person to be ordained a minister in the New England colonies.

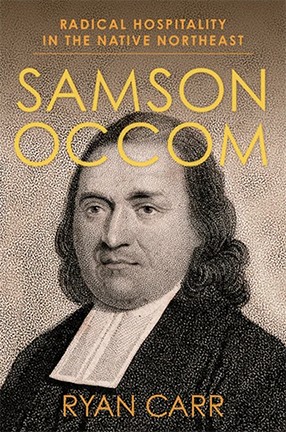

Samson Occom (1723-1792) was a prominent political and religious leader of the Indigenous peoples of New York and New England, among whom he is still revered today. Samson Occom: Radical Hospitality in the Native Northeast by Ryan Carr, a lecturer in English and comparative literature and American studies, profiles the Mohegan-Brothertown minister.

An international celebrity in his time, Occom rose to fame as the first Native person to be ordained a minister in the New England colonies. In the 1770s, he helped found the nation of Brothertown, where Coastal Algonquian families seeking respite from colonialism built a new life on land given to them by the Oneida Nation. Occom was probably the most prolific Native American writer prior to the late 19th century. Most of his writings, however, have been overlooked, partly because many of them are about Christian themes that seem unrelated to Native life.

In his book, Carr argues that Occom’s writings were rooted in Indigenous traditions of hospitality, diplomacy, and openness to strangers. For Occom, evangelical Christianity was not a foreign culture, but a new opportunity to practice his people’s ancestral customs. Carr demonstrates Occom’s originality as a religious thinker, showing how his commitment to Native sovereignty shaped his reading of the Bible. By emphasizing the Native sources of Occom’s evangelicalism, Carr offers new ways to understand the relations of Northeast Native traditions to Christianity, colonialism, and Indigenous self-determination.

Columbia News recently caught up with Carr to discuss the book, as well as classic works he’s just read, his favorite book that no one else has heard of, and the guest list for his next dinner party.

What made you write this book?

I got totally absorbed by Occom’s writings. I can trace it back to one moment, when I was reading a sermon he wrote on the Gospel of Luke, and the concept of loving thy neighbor as thyself. Occom goes into a long disquisition on the meaning of the word thou, and how it has the power to grab the attention of people from all national, racial, and class backgrounds, even if they’re strangers to one another. I realized then that Occom was a person who thought about language in a profound way.

However, I only fully committed to writing the book after I started talking to people from the Brothertown and Mohegan communities, who also saw the importance of Occom’s writings, and, crucially, the need for his work to be better contextualized for enhanced reading and appreciation. Without a certain amount of knowledge about 18th-century politics, literature, and religion, it can be hard to understand why Occom was so great.

How was Occom able to rise to such a level of fame in his time? What was so singular about him?

Occom was brought up in a community that valued strangers. Interacting with people from outside the community was a way of acknowledging the world’s sacredness. In my book, I discuss how this helps explain why Occom excelled at talking to so many different kinds of people: This ability was a deeply rooted cultural competence.

I also suspect that Occom was hugely charismatic. In the 1760s, he did a preaching tour in England. If you look at the Samson Occom Papers at the Connecticut Historical Society, you can read fan letters in which English people write about the power of his preaching, and how overwhelmed they were by his sheer physical presence. Of course, Occom’s celebrity was overdetermined in some sense. After all, he was the first Indigenous person to be ordained as a Protestant minister. For 18th-century evangelicals, this had biblical significance. A few of them described Occom’s ministry as a turning point in world history.

Was there anything you learned during the research and writing of this book that surprised you, or was unexpected?

I know a lot about Samson Occom now. As much as I can know, or almost. But I also learned, from talking to members of his communities, that there are people who know and value Occom in a way I never will: Those who know him as an ancestor, or as an illustrious leader of their nation. The experience of sharing what I know with Occom’s communities, and also hearing from them about their knowledge (even if I’ll never know Occom as intimately) has been powerful and rewarding. It’s also given me a clearer sense of what scholarship can and can’t do.

Are there any classic works of fiction or nonfiction that you only read recently for the first time?

So many! The Poverty of Theory, a collection of essays, by E.P. Thompson. Legalism: Law, Morals, and Political Trials by Judith Shklar. The 12th-century philosophical novel, Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān (The Improvement of Human Reason), by Ibn Ṭufayl. The last of these I read because it’s on the syllabus for the Core Curriculum class, Contemporary Civilization, which I teach. My students love the book, and so do I.

What’s your favorite book no one else has heard of?

Travel in the Ancient World by Lionel Casson, who wrote several books reconstructing everyday life throughout the ancient Mediterranean. From what I can tell, his evidence consisted primarily of paintings on Greco-Roman pottery housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Based on his observation of these ceramics, Casson developed passionately defended theories about what it was like to live in antiquity. (He was a sort of anti-Keatsian in this respect.) I find all of his books enjoyable, even if they’re not 100% accurate.

Has a book ever brought you closer to another person, or come between you?

My partner, Lina, and I read The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole at a formative stage; I’m not sure what that says about our relationship, but we are very close. I don’t think I could be friends with anyone who couldn’t find a way to love Henry James’s Portrait of a Lady. I’ve also occasionally accosted—or wrote to—writers whose books I admire. Philosophy Professor Akeel Bilgrami is an example. Connecting with people through their writing is an under-recognized privilege of being a scholar.

You’re hosting a dinner party. Which three scholars or writers, dead or alive, would you invite, and why?

Well, first of all, Samson Occom. But if he can’t make it:

Geoffrey Chaucer. He’d be a zealous eater, and a great listener. He could also let me know if my Middle English pronunciation is any good. I love reciting the General Prologue of The Canterbury Tales.

Baruch Spinoza. The most creative and committed philosopher I know of, who made friends with many different kinds of people.

Lord Byron. I suspect he’d be a little overbearing during dinner, but I’d like to have him around later in the evening.