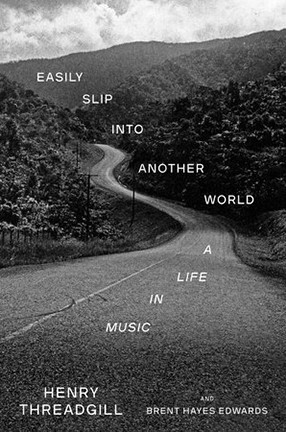

Brent Hayes Edwards Helps Write the Life of Another Artist

In Easily Slip Into Another World, he shapes the tale of musician Henry Threadgill.

Henry Threadgill has had a singular life in music. At 79, the saxophonist, flutist, and composer is one of three jazz artists (along with Ornette Coleman and Wynton Marsalis) to have won a Pulitzer Prize. In his autobiography, Easily Slip Into Another World, written with Brent Hayes Edwards, the Peng Family Professor of English and Comparative Literature, Threadgill recalls his Chicago childhood, his family life and education, and his musical career.

Recollections range from the music scene in Chicago in the early 1960s to his time touring with an evangelical preacher; his military service in Vietnam (representative of an under-recognized aspect of jazz history, given the number of musicians in Threadgill’s generation who served in the armed forces) to the global travels that enriched his art; to his immersion in the downtown scene of New York City in the 1970s and 1980s, when he collaborated with choreographers, writers, and theater directors, as well as a wide range of musicians. Threadgill also shares his thoughts on the recording industry, music education, and the history of Black music in the United States, as well as his work with the various ensembles he has directed over the past five decades.

Columbia News caught up with Edwards to discuss the book and the experience of co-writing someone else’s autobiography, along with who he and Threadgill might invite to a dinner party they would co-host.

How did your involvement with Easily Slip Into Another World come about?

You could call it an extended detour from one of my ongoing scholarly projects. For some time now, I've been working on a cultural history of the downtown jazz scene in New York in the 1970s, when multimedia collaborations flourished among musicians, dancers, writers, photographers, painters, and video artists. I've been interviewing dozens of artists about their work during this period, when many of them ran performance spaces and galleries in former industrial lofts in SoHo and the East Village.

I first interviewed Henry for my book back in 2006, and a couple of years later, he asked me to do a formal oral history with him about his entire life and career. Over the next few years, we recorded dozens of hours of our conversations. But as we continued to meet and talk, the oral history gradually evolved into a book project. We decided to take all the material we'd amassed and craft it into a literary autobiography.

What was it like to work with Threadgill on his autobiography? Was it the first time you've partnered with someone on a book? Can you describe the process?

I’ve done a lot of collaboration, from translations to co-edited books and anthologies, to co-written articles and introductions. I've also done a handful of multimedia performances with musicians and dancers over the years, going back to my own brief and emphatically minor career as a modern dancer in the 1990s. Writing with colleagues, I've done it various ways—dividing up sections to compose individually; editing and expanding each other's drafts; or even sitting down together in a tortured negotiation over every single word and phrase.

Working with Henry turned out to be different from any collaboration I'd done before. Although he was deeply involved throughout the process, Henry made it clear that the writing was my responsibility: It was up to me to figure out how to orchestrate his story on the page, from the broad organization of the book to its granular, sentence-to-sentence flavor.

It felt daunting to try to find a literary form that would somehow be adequate to Henry’s achievements in music. At the same time, I came to realize that there was a profound lesson in Henry's approach to collaboration. His extraordinary openness is partly a product of the particular dynamics of musical performance. In writing, someone has to have the final say: One person makes the final edit or, even if you're doing it together, only one of you is sitting at the keyboard. But in music, especially music that privileges improvisation, a composer has to be comfortable with a player bringing their own contribution into the mix. You have to be able to yield a certain amount of authority over the final product.

A few people have said to me that they find the book compelling in the way it feels like a combination or a melding of Henry's voice and my own voice as a writer. Sometimes they seem surprised at the observation. But how could it be otherwise? In the same way one could say that the cellist Diedre Murray is an integral part of Henry's great 1980s band, the Sextett, or that the guitarist Liberty Ellman is central to the identity of Henry's group, Zooid, of course I'm there in the sound of the book.

Any books you've read lately that you would recommend, and, if so, why?

I'm the editor of PMLA, the journal of the Modern Language Association of America. We're preparing a special section of articles about Hernan Diaz's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, Trust, which is not only a brilliant meditation on the history and heady excesses of American capitalism, but also, as it turns out, a powerful reflection on the ethics of trying to help someone write their life story.

What's next on your reading list?

Ilya Kaminsky's Deaf Republic, a timely poetic meditation on war, disability, and dissent; Aidan Levy's Saxophone Colossus, an appropriately colossal biography of Sonny Rollins; an advance copy of Adam Shatz's The Rebel's Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon.

What are you teaching this semester?

I'm teaching my undergraduate seminar, Writing Across Media, which focuses on multimedia art that combines literature with other media (dance, photography, music, painting). It's a fun class to teach because it includes a workshop element: The students get a chance to try out various techniques.

What are you working on now?

A French edition and English translation of the collected articles and short stories of the pioneering Martiniquan journalist and editor Paulette Nardal; and a book about African diasporic intellectuals and the politics of archival work (that is, collecting, classifying, and preserving documentary records), which emerged out of a graduate seminar I teach using collections in Columbia's Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

You're hosting a dinner party. Which three scholars or musicians, dead or alive, would you invite, and why?

I'm tempted to get interdisciplinary, but I think we'd need a bigger table. So let's stick with music. And I think it would have to be Henry and me co-hosting. His listening habits are astonishingly broad, but maybe we could convene a summit of some of the giants of African diasporic music he's never had a chance to meet: How about Bebo Valdés, Moacir Santos, and Mulatu Astatke. We'd need a small ensemble of interpreters, too. I imagine us all crowded around a tiny kitchen, laughing and swapping tales as we cook up something none of us would have made on our own.