A Family’s Odyssey From Eastern Europe to the Americas

Professor Claudio Lomnitz recounts his family’s history across continents and the 20th century.

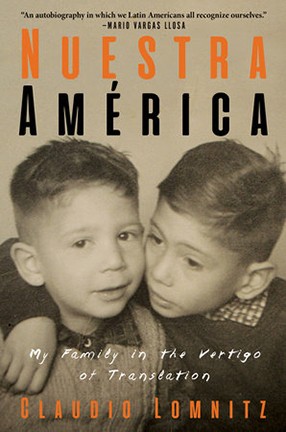

In his new book, Nuestra América: My Family in the Vertigo of Translation, Anthropology Professor Claudio Lomnitz traces his grandparents’ exile from Eastern Europe to South America in the 1920s. Trained to defy ghetto life with the pioneering spirit of the early Zionist movement, the couple became involved in the Peruvian leftist intellectual milieu and its practice of connecting Peru’s indigenous past to an emancipatory internationalism that included Jewish culture and thought. After being thrown into prison supposedly for their socialist leanings, Lomnitz’s grandparents were deported to Colombia. The story then continues to Chile during World War II, Israel in the 1950s, and, finally, to Lomnitz’s youth, living with his parents in Berkeley, California, and Mexico City.

Lomnitz discusses the book with Columbia News, along with why he’s leery about making reading recommendations, and what transpired when he ran into Claude Levi-Strauss during his student days in Paris.

Q. Why did you write a memoir at this point in your life and career?

A. I rarely know why I write, and that's a good reason for doing it. Writing is like finding my way through the fog, which is why it is exciting, but also sometimes hard. To prolong the metaphor, writing about one's own family implies a willingness to work in and through an especially impenetrable fog. I suppose that I felt the need to grope around in there for a while.

Q. What was the main difference between writing about yourself and your family versus writing something scholarly?

A. The biggest difference was that I felt the compulsion to write this book, despite lacking the scholarly credentials to do it. I always knew that if I didn't write it, nobody else would. But this meant writing about Jews without being a Jewish historian, and working through scenes that were set in places like Bessarabia, Rumania, the Soviet Union, Peru, Colombia, Israel, and Germany, without having the requisite expertise on any of those places. I've always been a bit of a dilettante, even in my academic work, playing on fringes that I can never truly master, but in this book, I went the whole nine yards.

Q. Any reading recommendations?

A. When you get on a plane, a flight attendant (or, now, a prerecorded message) tells you that, if there is a change in cabin pressure and the oxygen masks come down above your seat, you should put your own face mask on first, and only then try to help the person sitting next to you. I'm currently still struggling with my own face mask. In other words, my recommendation is: Choose your own reading.

Q. What’s your favorite book that no one else has ever heard of?

A. Many of the projects that I have worked on over the past 20 or so years have been historical, so I regularly find myself reading books that few people now read. At the Columbia Libraries, those books are usually "off-site," and often they don't yet have their bar-codes, and still carry their old library cards in a side pocket, so I can see who was the last person who checked the book out.

Sometimes, I have illustrious predecessors in my choice of readings. For instance, when I was writing The Return of Comrade Ricardo Flores Magón (2014), I needed to find out something about table manners in Mexico in the early 1900s, so I checked out the most famous Spanish manual on the subject, the so-called Manual de Carreño. Naturally, Columbia has a first edition (1898 or so), and the last person to have checked the book out before me turned out to have been Carmen Miranda, in 1940!

All of this is to say that I don't know what my favorite books are, but I do enjoy communicating with the dead.

Q. You're hosting a dinner party. Which three scholars or academics, dead or alive, would you invite and why?

A. I would invite close friends who I've not seen for way too long now.

I can be a bit withdrawn about meeting people who I've long read and admired. One time, when I was a student in Paris, I was at a reception, and right there in front of me was Claude Levi-Strauss! He was alone for a moment, just standing there with a glass of white wine in his hand, so I thought I should go over and talk to him. But what would I say? "I admire your books?" (Who doesn't!) So I decided just to brush past him, on the off-chance that some of his genius might rub off on me.

Check out Books to learn more about publications by Columbia professors.