The Daughter of An Immigrant and A Veteran Chronicles the Vietnam War Era

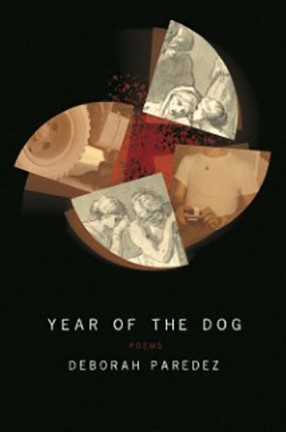

In her new poetry collection, "Year of the Dog," Professor Deborah Paredez invites readers to question the ways we document our history.

In the tradition of women as the unsung keepers of history, Professor Deborah Paredez’s second poetry collection, Year of the Dog, tells her story as a Latina daughter of the Vietnam War. Columbia News caught up with her recently to discuss the book—just cited as a new and noteworthy book of poetry by The New York Times—as well as poetry she recommends during quarantine, what she plans on reading next and who she would invite to a literary dinner party.

Q. How did you come up with the idea for this book?

A. Year of the Dog is a Latina feminist chronicle of the Vietnam War era. The title of the book evokes the year 1970—"Year of the Metal Dog" in the lunar calendar—which was the year of my birth, of my father's preparations for his departure for Vietnam, and of tremendous political and social upheaval. The title also refers to the mythic Greek figure of Hecuba, who responded to the atrocities of war by committing herself so fully to her grief that she was transformed into a howling dog.

The book situates first-person poems from my perspective as the daughter of a Mexican immigrant and Vietnam veteran among poems about other historical and mythic women responding to Vietnam and other forms of domestic and international warfare—as warriors, widows, antiwar activists and witnesses of violence. At the center of Year of the Dog are the perspectives of women of color, who have remained largely absent from prevailing remembrances of the Vietnam era and who, like Hecuba, undergo and provoke epic transformations through their acts of lamentation.

Q. What genres do you use in the book in addition to poetry?

A. The book includes poems in an array of received and invented forms and a selection of collaged images drawn from snapshots my father took in Vietnam and iconic photographs from the era. In this way, the book highlights and questions the limits of documentation during a war marked as one of the most documented in history. The poems shift perspectives from the personal lyric to more collective references, foregrounding the lamentations and the silences of mythic and historical women, in particular those classified as "others." The interplay between image and text and between family history and national history encourages a de-familiarizing of events and historical figures such as the Kent State shootings, Angela Davis's arrest, Latinx histories, Walter Cronkite counting the daily dead on the nightly news, iconic images of Huey helicopters and napalm attacks on villagers in Vietnam.

Vietnam is also known for its relationship to silence—the war Americans still struggle to discuss or come to terms with. As such, the era—simultaneously well-documented and undocumented—invites an interrogation not just of the war or the antiwar movement, but of the very truth and value of the silences that persist in the processes of documentation itself.

Q. What is it about women’s voices that make them so powerful?

A. I first read Euripides' Trojan Women when I was 12 years old, which is right around the time I started writing poetry. My journey in poetry has always been guided by the echoes of women's grief. On the ground level, many of the poems in Year of the Dog emerged from my experiences as the daughter of an immigrant and a veteran and my early yearnings to speak into the silences that permeated our household and the culture at large about the legacies of war. Beyond this, though, and crucial to the larger structure of the book, is a Latina feminist embrace of an elegiac tradition among women—both mythic and historical—who were often relegated to the margins of society. This isn’t surprising, in light of the fact that a central figure in Mexican folklore is La Llorona, the weeping woman who haunts the riverbanks mourning her children and threatening to disturb our complicit comfort in the present.

In my book, my story is interwoven with those of other women who are transformed through their acts of outcry against war, everyday violence and injustice. In addition to Hecuba, there are references to Lot's wife, who stands and bears witness to the burning city until she is transformed into a pillar of salt, along with, among others, Angela Davis and Mary Ann Vecchio, the girl in the iconic Kent State shooting photos.

As much as I want to encourage a new way of seeing and talking about a particular moment in history (the Vietnam War), I also hope that readers get a sense of how it has always been "war time" and how women's voices of outrage have always been at the center of the elegiac tradition. I finished this book in 2018, another Year of the Dog, and a year that had the highest number of school shootings in U.S. history. Year of the Dog is being released during a global pandemic in which pervasive inequalities along lines of race, class and gender are being exposed and exacerbated. So I hope readers come away with the sense of a nonlinear progression of time and a deep questioning of the ways we often document our histories.

Q. Are there any books of poetry or other works of literature that you recommend during this quarantine period?

A. There have been many challenging moments during the last several years when I’ve turned to Ross Gay's poetry collection, Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude. I continue to find his attentiveness to everyday connection—to neighbors or the natural world or to difficult emotions—a balm during these times.

Q. What is the last great book you read?

A. A handful of books I've read recently that moved and inspired me are Anne Boyer’s The Undying, my colleague Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval, Ilya Kaminsky’s poetry collection Deaf Republic and another book of poems, Tracing the Horse by Diana Marie Delgado.

Q. What is on your reading list now?

A. Don Mee Choi’s DMZ Colony, Postcolonial Love Poem by Natalie Diaz and my colleague Rashid Khalidi's The Hundred Years' War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917-2017.

Q. What do you tend to read more, fiction or nonfiction?

A. I write poetry and essays and am most interested these days in works that blur the lines between these two genres.

Q. What are you working on now?

A. I am finishing up a book of essays about how divas, and divas of color in particular, have shaped my life and American culture more broadly. These essays reflect on why we love (and love to hate) divas and how the very concept of "divas" has informed our thinking about feminism, free market principles and freedom struggles during the last 50 years.

Q. You're hosting a dinner party. Which three scholars or academics, dead or alive, do you invite and why?

A. I'd want thinkers in the room who were also poets or at least had a poetic sensibility that informed their thinking. So I would include Audre Lorde, Gloria Anzaldúa, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Robin D. G. Kelley and Angela Davis.