Freeing the Girl From Napalm

A two-day conference at Columbia looks back at the Vietnam War and the lives it touched.

Optimism abounds in Phan Thi Kim Phuc, a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador and peace activist. Her optimism is a miracle. In 1972, the world was shocked by a photograph of a girl running, arms outstretched, away from the site of a bombing. Her clothes had been burned off by napalm; her expression was one of immense pain.

That photograph, titled “The Terror of War,” but known to many as “Napalm Girl,” was for many years a source of shame for Phuc, the photo's subject. Nick Ut, then a photographer for The Associated Press, caught Phuc at her most vulnerable—naked and suffering—and cemented her eternal position as a poster child of victimhood.

Phuc nearly died that day. Ut rushed her quickly to a hospital, where she was bandaged; but with her condition so precarious and hospital staff so overwhelmed, she did not receive further medical attention at that time. She was discovered by her family, barely alive, at the morgue where she had been dropped off three days prior. (This negligence actually saved her life, as the three-day period in which her bandages were not changed allowed the effect of the napalm—which burns when exposed to oxygen—to weaken.) She recovered, but could not escape the shadow of the image, as she was made to promote government propaganda for many years until she defected to Canada in 1992.

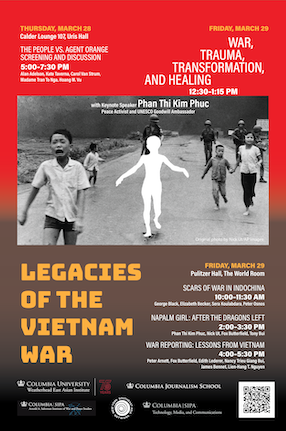

Through countless operations, her burns have healed. But more important, so has her heart. In her March 29 keynote address at a "Legacies of the Vietnam War" conference hosted by the Weatherhead East Asian Institute (WEAI) and co-sponsored by the Columbia Journalism School; Arnold A. Saltzman Institute of War and Peace Studies; SIPA Technology, Media, and Communications; and the New York South East Asian Network, Phuc recounted her journey through “War, Trauma, Transformation, and Healing.” Like a cup of black coffee being poured out––her own metaphor––Phuc gradually let go of her bitterness toward her past and the photo that haunted her.

“We cannot change history, but with love we can change the future,” Phuc said.

A public panel discussion was hosted shortly after the keynote luncheon. Joining Phuc were the photographer behind the image Nick Ut (who won a Pulitzer Prize for the shot and is the only Vietnamese person who earned that distinction during the war); and Fox Butterfield, a journalist who was at the scene that day on assignment with The New York Times. The discussion included a rundown of each panelist’s account of the day of the photo: June 8, 1972, when a pagoda filled with civilians was hit by a U.S. bomber with napalm. Butterfield recalls that the South Vietnamese forces piloting the attack appeared to have mistaken North and South Vietnamese targets, striking a civilian target in an act of “friendly fire.” The conversation was led by WEAI artist-in-residence Tony Bui, who is currently writing a film screenplay, tentatively titled “When the Dragons Came,” based on the events of the day.

The two-day “Legacies of the Vietnam War” conference began on March 28 with a screening of “The People Vs. Agent Orange,” a compelling documentary that follows two activists working across continents to stop the use of the chemical herbicides comprising Agent Orange, and to find justice for the victims.

A panel discussion followed the screening, featuring producer-director duo Alan Adelson and Kate Taverna. They were joined by the subjects of the film, French-Vietnamese activist Madam Tran To Nga, who led a lawsuit against the U.S. manufacturers of Agent Orange including Dow Chemical and Monsanto; and American Activist Carol van Strum, who fought to ban Agent Orange components 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D, and the spraying of these herbicides in Oregon forests.

Despite these women activists’ connection as leaders in the fight against the use of Agent Orange, their appearance at Columbia marked their first-ever meeting. Hoang Minh Vu, a postdoctoral research scholar at WEAI and a consultant on the film, moderated the discussion.

A full day of events on Friday started with “Scars of War in Indochina,” with journalists George Black, Elizabeth Becker, and Peter Osnos, along with Legacies of War CEO Sera Koulabdara. Each panelist, prompted by moderator Peter Osnos, brought to the discussion first-hand accounts from the countries of the region: Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos. Becker, a former stringer for The Washington Post, recalled Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge and the chaos of shifting U.S. allegiance. Black spoke about his time in Vietnam, notably attesting to the resilience and warmth of the people of Vietnam in the post-war period, despite the scars of war they carry with them. Rounding out the panel, Koulabdara highlighted the mission and work of Legacies of War, and shared her harrowing personal experience witnessing the dangers of unexploded ordnance. The U.S. dropped more than 2 million tons of bombs on Laos in the 1960s and '70s.

The final event of the conference was a panel discussion titled “War Reporting: Lessons from Vietnam,” which brought together award-winning journalists whose brave work from on the ground revolutionized war reporting as a field and shaped public perceptions about the Vietnam War. Fox Butterfield reprised his role as panelist and spoke about his work on the Pentagon Papers. AP reporters Peter Arnett, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage; and Edith Lederer, who was the first U.S. woman war correspondent in Vietnam, also shared their experiences, along with Nancy Trieu Giang Bui, who was a reporter for a South Vietnamese newspaper, Sóng Thần, and now leads Vietnamese American Heritage Foundation. WEAI Director Lien-Hang T. Nguyen and James Bennet, senior editor at The Economist, moderated the event.

Ariana King is senior communications coordinator at the Weatherhead East Asian Institute.