A Fresh Perspective on Rastafari Culture and Cosmology

In An Ethos of Blackness, Vivaldi Jean-Marie reexamines the movement’s core beliefs and practices.

Rastafari is an Afrocentric social and religious movement that emerged among Afro-Jamaican communities in the 1930s and has many adherents in the Caribbean and worldwide today. An Ethos of Blackness by Vivaldi Jean-Marie, who teaches in the African American and African Diaspora Studies Department and is a philosophy professor at the City University of New York, offers a new account of Rastafari. The book provides a normative conception of Blackness for people of African descent that resists Eurocentric and colonial ideas.

By examining Rastafari’s core beliefs and practices, Jean-Marie argues that they constitute a distinctively Black system of norms and values—at once an ethos and a cosmology. He traces Rastafari’s origins in enslaved people’s strategies of resistance, Jamaican Revivalism, and Garveyism, showing how Rastafari incorporates ancestral religious traditions and emancipatory politics. An Ethos of Blackness draws out the significance of practices such as avoiding technological exploitation of natural artifacts and the belief in living in harmony with the natural order. Jean-Marie also considers Rastafari’s theology, exploring its reinterpretation of biblical scriptures and its foundations in the rejection of Christianity’s Eurocentrism and racism. But, he insists, before Rastafari can fulfill its promise of liberation for people of African descent, it must confront its failure to include women and redress sexism.

Jean-Marie talks about the book with Columbia News, along with what he’s read lately, what he avoids reading while writing a book, and who he would like to invite to a dinner party.

How did this book come about?

I was inspired by my ruminations on how the Rastafari movement illustrates one of the axioms of political philosophy, specifically, that a nation-state and a people are concomitant to the elaboration of a system of socio-cultural norms, values, and religious beliefs. This axiom was the unifying thread in my textual reading and empirical observations of the rituals and social and communal practices of Rastafari.

I concluded that Rastafari strives to elaborate an alternative system of norms, values, and religious beliefs to those that people of African descent in the Diaspora inherited from slavery and colonialism. An Ethos of Blackness articulates this alternative system, by means of which Rastafari delineates an Afrocentric conception of people of African descent.

Can you give some examples from the book of how Rastafari provides an alternative conception of Blackness?

One example is an I-tal diet, which may be interpreted as a mechanism to redress the colonial and post-colonial strategy to assimilate Africans and people of African descent in the prescribed diet of plantation slavery and colonialism. For Rastas, this methodical dietary assimilation was a form of subjugation, in addition to the physical subjugation of Africans and people of African descent. Hence, an I-tal diet is a way to undo the systematic dietary assimilation that happened on plantations.

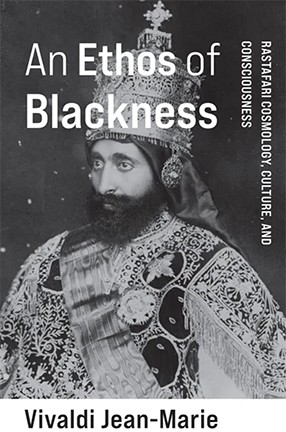

Another example is Rastafari Black theology, which remedied the biblical accounts of people of African descent. The crowning achievement of Rastafari Black theology’s brokering with Christian orthodoxy is the assertion of an intrinsic Black divinity—Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie I (1892-1975)—in the humanity of people of African descent. Selassie as the Black Godhead transforms Africans and those of African descent as multiplicities of Black divinity. This novel Afrocentric narrative of Rastafari Black theology provides a panacea to address many of the religious and psychological traumas that slavery and colonialism inflicted on people of African descent.

Did you make any personal discoveries during the writing process about your own theological imagination or anything else?

After discovering that Martin Luther created a pictorial illustration of God, Adam, and Eve as Europeans to accompany his 1534 Bible (also known as the Weimar Bible), I concluded that Martin Luther played a key role in framing a Eurocentric Christian theology by depicting biblical figures as white Europeans. In addition, this undermined God as a sheer spiritual entity and broadcast the popular image of God as a white patriarch, furthering the idea of the original humans as white people. This notion was also promoted by the paintings of the Renaissance.

A major Rastafari goal is to offer an alternative to Martin Luther’s Eurocentric framing and undermining of God as a spiritual entity for people of African descent. Rastas adopted Haile Selassie as their Godhead and argued that the original humans were Ethiopians.

Are there any classic books you've read only recently for the first time?

Albert Camus’s The Fall, Marguerite Yourcenar’s Memoirs of Hadrian, and Angela Davis’s Women, Race, and Class.

What do you read when you're working on a book? And what do you avoid reading when working on a book?

I read French literature for imagery. It helps me to balance the rigidity of academic writing. I avoid reading sensationalist news media.

What are you teaching this semester at Columbia?

I am teaching The Haitian Revolution as a Sketch of Blackness, and African-American Research Writing as a graduate thesis seminar.

You're hosting a dinner party. Which three academics/scholars, dead or alive, would you invite, and why?

Alain LeRoy Locke—for his brilliant analysis of African American aesthetics and his unmatched elaboration of epistemology and pragmatism from a Black angle.

David Hume—for his magisterial discussion of resemblance, contiguity, and causation as the intricacies of belief, which is the core concept of epistemology.

Michel Foucault—because throughout his corpus, he demonstrates that knowledge is always the collective construction of human beings in the specific context of their cultural, social, political, and scientific institutions.

Check out Books to learn more about publications by Columbia professors.