The History of the Women Who Founded Columbia's Most Prolific Community Service Efforts

Starting with the sale of a single bouquet from Isadore Gilbert Mudge’s garden in 1942, Columbia Community Service, largely run by women over the past 82 years, has raised millions of dollars in support of nonprofits serving Harlem and Morningside Heights.

A top librarian of the 20th century with a garden and a calling to service. A Manhattan portrait painter and granddaughter of abolitionist and suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton. A “faculty wife” of the former dean of Columbia Engineering who organized countless student events and ran a local charity shop to benefit Uptown nonprofits.

In 1942, three women founded what is known today as Columbia Community Service (CCS), one of the most prolific and longest-lasting philanthropic and community engagement initiatives of Columbia University. Their names: Isadore Gilbert Mudge (1875-1957), Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake (1894-1981), and Lolita Mollman Finch (1882-1964).

To date, their efforts to encourage charitable giving to our local community have inspired more than $7 million in donations from faculty, staff, and retirees of Columbia, Barnard, and Teachers College. The programs CCS supports combat hunger, provide social services, support the arts, and offer educational enrichment for youth in STEM, arts, and literacy in Harlem and Morningside Heights.

The three women originally came together amid World War II to raise money to benefit war relief efforts. Their work, however, expanded even further after the war under the name “Columbia Committee for Community Service,” including sending funds to Peking, China for the treatment of tuberculosis, the development of a “Children’s Programs Series” to provide enrichment for underserved youth in Upper Manhattan, and student loan funds.

Their efforts, including a charity gift shop and an incredible cookbook of Columbia recipes designed to “help cook Hitler’s goose,” were the foundation upon which CCS, as we know it today, was born. They were not alone in this work, with many Columbia women joining the administration and the day-to-day operations of CCS in its nascency. While CCS has grown to be a success over the years through the efforts of people of all gender identities, it should be noted that even today, it is led by women dedicated to serving Columbia's neighbors in need.

This Women’s History Month, we’re looking back at the stories of the women founders of CCS, with an eye to the living history of the organization today. If you would like to support the work of Columbia Community Service, you can always do so here.

Isadore Gilbert Mudge (1875-1957): An Iconic Librarian

At the very end of her 30-year tenure as Columbia University's head reference librarian, Isadore Gilbert Mudge made a decision that would forever alter the history of community service at Columbia: the sale of a bouquet from her personal garden.

A venerable woman by any account, John Neal Waddell wrote in his 1973 dissertation that Mudge was "the most prominent reference librarian of the 20th century to date," who literally wrote (and edited) the American Librarian Association's Guide to Reference Books for more than 20 years.

"In editing that book, she provided a source for hundreds of librarians to use as a yardstick in building strong reference collections as well as supplying a basic textbook for generations of library students," Waddell wrote. "Mudge became not merely a woman's name but a noun, an adjective, and a verb upon the lips of librarians and students in the entire English-speaking world."

Mudge, who was noted as a "strong individualist and extremely colorful person," came to Columbia University in 1911, where for 30 years she completely rejuvenated how Columbia Libraries approached the acquisition and organization of reference works (such as encyclopedias, dictionaries, thesauruses, periodicals, government manuals, and introductory texts to a variety of subjects). By 1941, she grew the reference collection to more than 18,000 volumes where it was previously next to nonexistent through a "build upon failure" policy (whenever someone requested but could not locate a text, Mudge would look into acquiring it).

At the time, her work helped grow Columbia Libraries to the third-largest library in the country by organizing the reference collection in one place rather than scattering it across campus in subject-area-specific libraries. She achieved this "not always tactfully, but certainly doggedly," Waddell wrote, bringing a tireless energy to get others to believe in her way of organizing a library.

"She had one of those clear, sharp minds, one which went from one thing to another so fast that you couldn’t keep up with her," said her protégé Constance Mabel Winchell in an oral history interview in 1963. "I think lots of times near-geniuses are that way. They’re not just ordinary people. And Miss Mudge was not an ordinary person in any sense of the word. She was an extraordinary person.

"Therefore, while some people used to get upset at various of her actions, others knew she was a phenomenal aid; that you had to take her whole. You couldn’t take one part and leave the others. She was a person the like of which doesn’t exist very often."

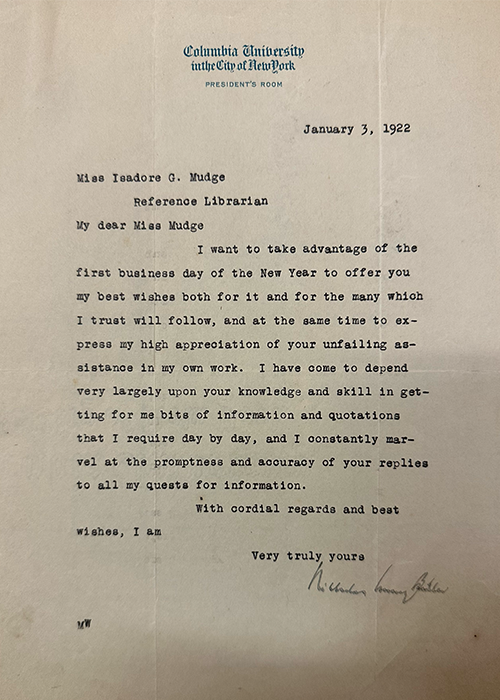

In addition to her full-time job as head reference librarian, which she was promoted to within three months of her employment at Columbia, and the editing of seven editions of the Guide to Reference Books, she was also President Nicholas Murray Butler's personal contact at the library, persistently searching for confirmation of quotes and information for his abundant speechmaking and writing. This is all without mentioning how she taught more than 200 library students at Columbia's School of Library Science.

In her spare time (leading one to wonder: did she sleep?), Mudge was also known for tending a large personal garden, which Winchell recalls in perfect detail:

"When she worked out in her garden she wore knickers — if you wanted to be free of a skirt, in those days, you wore knickers and a shirt that came down over them. Usually, the knickers wouldn’t stay around her knees, so one of them was usually hanging down, like small boys'. The garden was very apt to be wet and dirty, particularly in the spring, and she would wear these large, flapping galoshes, which she wouldn’t bother to buckle. It really was a wonderful sight, which I used to enjoy thoroughly."

Even as Mudge announced her retirement from Columbia Libraries in 1941, she turned to her garden in one more act of service for the Columbia community by cutting flowers and transforming them into bouquets, which she sold as part of the war relief effort alongside her friends Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake and Lolita Mollman Finch. It was this simple act through which Columbia Community Service would be born.

You can read more about Mudge and her tenure at Columbia in a collection of her papers in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Mudge died in 1957, but her legacy lives on in the American Library Association's "Isadore Gilbert Mudge Award," which presents a monetary prize of $5,000 and a citation to an individual who has made a distinguished contribution to reference librarianship.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake (1894-1981): Carrying the Torch of Women's Leadership

You might say women's leadership runs in the family, when it comes to Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake. The granddaughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, noted women's suffragist and abolitionist, Blake was a groundbreaking woman in her own right.

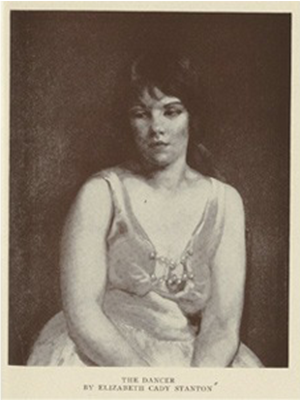

Early in her life, Blake was a student of the Art Students League in New York City and was even mentored by Cecilia Beaux before becoming a professional portraitist and painter. Her work was frequently exhibited by the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors (now known as National Association of Women Artists [NAWA]) and she eventually became president of the organization from 1928 to 1930, expanding NAWA's archival collection of women's work from the 1920s and 1930s to Washington D.C.

Blake was very much a woman of contradictions, declaring in an oral history interview in 1975, "I was not for women’s lib in spite of the Elizabeth Cady Stanton name," and all but abandoning her professional career as a portraitist when she met and married William Blake, who headed the English Department at Teachers College and Horace Mann School.

At the same time, she broke barriers and celebrated women in almost every direction she turned, explaining her advocacy with NAWA and, later, CCS.

"I did feel that women should have the chance to be professionally equal to men," said Blake. "I could see no reason why an artist, who was a good artist and worthy of it, shouldn't have the same respect shown her and have this well-known career as any man."

While Blake "came to Columbia as a bride," she made her mark on the community in her attempt to connect the wives of Teachers College and Columbia University faculty.

"At that time it was quite amusing to me as an outsider coming in to see how wide the valley was between 120th Street and 116th," Blake said.

It was through this connection-making that Blake came to know Mudge and Finch and began war relief efforts in 1942. At the urging of Mrs. Nicholas Murray Butler, Blake, alongside Finch, became one of the charter members of the gift shop committee, which first raised money for war relief by selling cookies, cakes, and preserves before turning toward raising funds for local organizations.

"In those first days, we were in Casa Italiana," Blake said. "It was new then and one flight up in that big auditorium is where during the war the Red Cross workers met. We folded bandages and so forth, all the wives did. We worked very hard. Then, at the bottom of the staircase in the corner was where we had our shop, which was very small, but everyone coming in or going out would see us and it was quite successful."

These beginnings as a small shop would eventually grow into a brick-and-mortar outfit on West 117 Street that would raise funds for the next 20-some years.

You can read more about Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake at the National Association of Women Artists and in the Elizabeth Blake Papers at Columbia's Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Lolita Mollman Finch (1882-1964): Entrepreneurial Spirt in Service

Lolita Pauline Mollman Finch could be considered the most traditional of CCS founders, most commonly identified by her connection to husband James Finch, the dean of Columbia Engineering from 1941 to 1950, as "Mrs. James Kipp Finch." To do so today, however, would be to diminish the impact she had on the Columbia community, CCS, and the Uptown community at large.

Traditional "faculty wives" as they were known then, were predominantly responsible for the connection-making and community-building among Columbia faculty and students, organizing teas, dances, networking, and civic service across campus for the benefit of all.

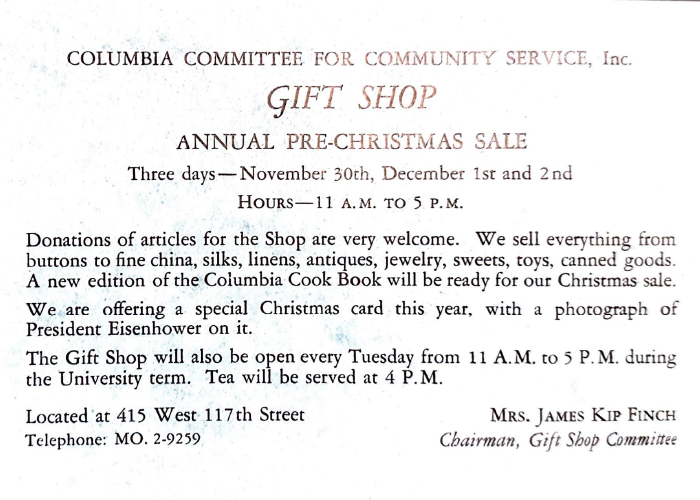

Upon joining Mudge and Blake in war relief efforts in 1942, it was Finch who professionalized the gift shop (after the war) under the auspices of the Columbia Committee for Community Service, moving its operations to the kitchen of a brownstone at 415 W. 117th St.

As the founder and president of the gift shop committee, Finch oversaw the acquisition of items for sale and the committee of women who staffed the shop throughout the year, including holiday bazaars. Proceeds from the various books, jewelry, dishware, paintings, and knick-knacks sold went to scholarship funds and local organizations, setting the stage for the service organization CCS is today.

In 1953, in the Columbia Spectator, Finch was "happy to report that since its founding, the committee had made approximately $50,000."

Finch would run the shop up until she died in 1964. At that point, the gift shop alone had raised more than $80,000 for local charities, aid organizations, and community centers.

The Legacy of Women-Led Service

Isadore Gilbert Mudge, Elizabeth Cady Stanton Blake, and Lolita Mollman Finch were not alone in their call to create what would become Columbia Community Service. Whether "faculty wives," faculty, staff, or retirees, dozens of women have long been the backbone of CCS, the vast majority of them volunteers in giving their time and talent.

From Elizabeth Cunningham Rappleye, wife of the former dean of Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, who founded the CCCS Thrift Shop in the 1940s and ran it for 30 years to fund scholarships and community organizations, to Nancy Rupp, wife of President Emeritus George Rupp, Karen Blank, former Dean of Studies at Barnard College, and Jean McCurry, Barnard College retiree and CCS board member, who shepherded CCS through its 50th anniversary and beyond, raising hundreds of thousands of dollars, women are central to the success of community service at Columbia.

Today, Columbia Community Service is led by three women staff members: Deb Sack, Vice President of Operations in the Office of Public Affairs (OPA), Shaba Keys, Associate Vice President of Strategic Initiatives in OPA, and Joan Griffith-Lee, Director of Columbia Community Service and a staff member for over 30 years. Between the Annual Appeal Steering Committee and Board of Directors, there are more than a dozen other women who take a leadership position with CCS today.

And we would be remiss not to mention the incredible women's leadership of CCS grantee organizations, which you can read about here and here.

If you believe in the legacy of such women-led service, we invite you to support CCS going forward, either by donating much-needed funds, giving of your time as a volunteer with a CCS grantee, or by becoming a CCS ambassador.

A special note of thanks to the librarians at Columbia's Rare Book and Manuscript Library, particularly Jocelyn Wilk, University Archivist, who helped us track down many boxes worth of documents and photographs to unearth the history of these women.