Where the Wild Things Are

Professor Jack Halberstam provides another way of looking at queerness and queer bodies in a new book.

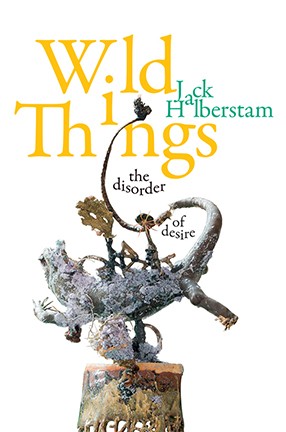

From zombies and falconry to Oscar Wilde and Max, Maurice Sendak’s beloved children’s book character, Jack Halberstam, a professor of English and Comparative Literature, offers an alternative history of sexuality by tracing the ways in which wildness has been associated with queerness and queer bodies in his new book, Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire.

Halberstam discusses the book with Columbia News, along with how the concept of “wild” has influenced authors and artists, what books he’s read lately and which ones he recommends, and why he would invite Emma Goldman to a dance party.

Q. How did you come up with the idea for this book?

A. I have always worked on the history of systems of classification for queer and gender variant bodies, so I was interested, in this book, in how and when some bodies get cast as “wild” or outside of systems of classification, or beyond the orders of knowledge designed to confine them. The category of the “wild thing” is all at once fantastical, radicalized, sexual, and monstrous. So I set out to give a cultural history of wildness.

Q. What are some of the ways in which wildness has been associated with queerness and queer bodies throughout the last century?

A. Many kinds of bodies have simply been cast as wild by civilizational and colonial discourses. By the late 19th century, the category of wildness was most often applied to indigenous people and Black people in particular. Counter-discourses began to appear by then, narratives that commandeered the terrain of nature and the anti-natural to express a deep distrust of emergent normative medical, social, and political systems of knowledge.

Some queer people have cleaved to the idea of the “natural” to justify their existence (the writer Radclyffe Hall, for example); others, like Oscar Wilde, have located themselves against nature, and still others have taken refuge in a fantasy of wild life, wild desires beyond the scripts of the natural, the normal, and the human. There are chapters in the book on writers who are fascinated by feral birds of prey, on colonial administrators, on zombies, and a few chapters on animal-human relations to wildness.

Q. How does wildness transgress Euro-American notions of the modern liberal subject?

A. Wildness is the rejected terrain upon which modern liberal subjectivity has been formulated. It is the chaos against which civilization fights, the anarchy that state authority opposes, the disorder that systems of knowledge try to tame. Wildness is also a great way of situating anticolonial and queer material alongside each other.

We can see this in the gorgeous canvases of First Nation artist Kent Monkman, a Cree, Two Spirit painter who has reimagined modernist art through his own queer and anticolonial representations of colonial Canadian history. In various canvases, he restages encounters between white settler colonials and native peoples, and makes wildness into a disordering force that undoes the relentless narratives of order, civilization, and domestication. Work like Monkman’s actively opposes the tidy, heteronormative narratives of human development.

Q. In terms of literature and the arts, what is it about that word—wild—that inspired everything from Maurice Sendak's Wild Things to Cheryl Strayed's Wild and Jon Krakauer's Into the Wild?

A. As you suggest, the world “wild” itself sounds like an invitation to riot. And it does operate that way in Maurice Sendak’s children’s book—a book that lends part of its title to my book. Where The Wild Things Are offers a vision of wildness embodied by monstrous, ruined creatures who have been pushed to the edge of time, and exiled outside of the ordinary space of the family home. Max goes to where the wild things are when he is angry with his mother, and because he is frustrated by his position in the familial home as a child. His impotence at home is countered by a new sense of sovereign power when he finds the place where the wild things are, and Max becomes a king there and leads the wild rumpus that ensues. But ultimately, Max leaves the place of wildness and returns home to take his proper place as a masculine subject in the world of his parents.

My book asks whether there is another future for wildness and wild things that does not require colonial rule or conquest, and that does not imply abandonment and ruination. Or, at least, I ask whether we might embrace the ruination as the end of the domestic order—the end, by implication, of a white world of law and order, the end of the family, the end of patriarchal rule.

By comparison, the other books you mention cleave to a version of wildness that is continuous with order and domesticity: Cheryl Strayed goes into the wild to find herself, and here the wild is just a kind of backdrop to a deeply conventional narrative about the struggle to find meaning in life. In Jon Krakauer’s version of the story of Christopher McCandless, the young male protagonist goes into the wild to lose himself and return to a mythic past. Neither author really sees in wildness anything much more than nature or the absence of human settlement.

Q. How have the pandemic and the racial-social justice protests contributed to the concept of wildness?

A. I think our current apocalyptic times have made us aware of the terrible consequences of human impact on the environment, on the one hand, and the dreadful outcome of white supremacist rule on the other. The protests that rocked cities this past spring and summer afforded a powerful glimpse of an anarchist, Black, queer, trans coalition of freedom fighters in this country who know that the only way to an alternative configuration of life, power, and society is through the active unmaking of the world we currently inhabit. I would call this political surge—wild.

Q. What books would you recommend to readers now?

A. The Dispossessed by Ursula Le Guin, an anarchist classic from 1974; Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments by my colleague Saidiya Hartman, for a counter-intuitive political history based upon the lives and movements of Black girls and women from the turn of the last century; Colson Whitehead’s Zone One, because we are in the zombie apocalypse, and this book shows us that the only true end for that apocalypse is for the zombies to win!

Q. What's the last great book you read?

A. There are many great books I have read recently: Jordy Rosenberg’s brilliant Confessions of the Fox—a retelling of the story of Jack Sheppard as a transgender thief, jail-breaker, and revolutionary. Blindness by Jose Saramago was an interesting read in the middle of a pandemic, given that it is about an epidemic of blindness. The heteronormativity of the book really bothered me, but it has stayed with me as a shocking account of quarantine culture.

The last truly great novel I read was Milkman by Anna Burns: Set in Northern Ireland during the Troubles, it tells the story of a young woman as she maneuvers through a landscape bristling with political menace. It does not sound humorous in this summary, but it is one of the most mordantly funny books I have ever read.

Q. What are you teaching this fall?

A. An Introduction to Sexuality course that studies modern sexuality against the backdrop of medicine, settler colonialism, institutionalized racism, and current regimes of power. The class allows students to think beyond contemporary identity politics, and to look carefully at the construction of historical archives while imagining alternative systems of kinship, resistance, and desire.

Q. You're hosting a dinner party. Which three academics or scholars, dead or alive, would you invite and why?

A. Oh boy, I am not good at dinner parties. Let’s make it a dance party and invite more than three: My late, great friend, the utopian queer theorist Jose Munoz because no party would work without him. Emma Goldman, so she could dance to the revolution; Eileen Myles and Fred Moten because they are both gorgeous poets and great company.