Jorge Otero-Pailos’s "Analogue Sites" Opens on Park Avenue

The GSAPP professor’s outdoor sculptures advocate for the experimental preservation of U.S. embassies.

Analogue Sites is a public art exhibition of large steel sculptures created by Jorge Otero-Pailos, a professor at the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, and director of its Historic Preservation Program. He made the works while preserving the former U.S. Embassy in Oslo, Norway, an Eero Saarinen-designed landmark. The exhibition, which opened on April 1, is presented by the Sculpture Committee for the Fund for Park Avenue and NYC Parks. Wrought from the fence that once surrounded the historic Oslo building, the sculptures are placed along Park Avenue at East 53rd, 66th, and 67th Streets, in dialogue with midcentury modernist landmarks like the Park Avenue Armory and Lever House. The works will remain on view through October 31.

Otero-Pailos discusses the exhibition and historic preservation with Columbia News, along with what he’s teaching this semester, and the joys of being a professor both at GSAPP and in New York.

How did this project come about?

Analogue Sites stems from a recognition of the historical significance embedded within modernist U.S. embassies built during the Cold War. As an artist and preservation architect, I've long been fascinated by the interplay of art, architecture, and cultural diplomacy. The idea for the project was sparked by my involvement in the extensive renovation of the Saarinen U.S. Embassy in Oslo, Norway, which I helped restore, together with a team of Norwegian architects and firms, from 2018 to 2023.

Through that experience, I came to appreciate the pivotal role these embassies played in shaping cultural exchange, and how vulnerable the buildings are today. The U.S. Embassy in Oslo, built in the late 1950s, was a beacon of openness, featuring amenities like a movie theater and a public library. Some of its qualities, such as its closeness to the street and its accessibility, made it unfit for today’s heightened security. In 2017, the structure was decommissioned and sold to a private developer. The Norwegian heritage authorities landmarked parts of the building. We wanted to preserve as much of the original fabric as possible, but the perimeter fence had to be removed to restore the building to its original 1959 state.

I was able to save the fence from the garbage heap by transforming it into sculptures. The fence thus acquires new meanings, while preserving the old ones. Three of these sculptures are installed outdoors on Park Avenue as part of my Analogue Sites exhibition. The works create a dialogue between the U.S. Embassy in Oslo and New York buildings on Park Avenue that are similar by some measures, such as the 1957 Seagram Building. Constructed as a corporate headquarters, it ran an ambitious, community-engaged public arts program for decades. Another example is the Park Avenue Armory, completed in 1880; it was originally built for military power, and reimagined in the 2010s as a center of soft power, art, and culture.

What makes Cold War Embassies worth preserving and reimagining?

These buildings are architectural masterpieces, designed by some of America’s greatest modern architects, including—in addition to Saarinen—Edward Durell Stone, Richard Neutra, Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, and Josep Lluís Sert. The structures all share unique design features, which are unimaginable in embassies today. They were equal parts cultural centers, immigration gateways, and diplomatic offices, with free and open public libraries, art galleries, and theaters. They therefore can inspire us to think more creatively about what our future embassies could be.

What does art bring to the architectural preservation process?

For me, art, architecture, and preservation are all different but complementary ways to care for the existing built environment. Any time we remove something from the built environment, we are potentially erasing important collective memories. Sometimes people don’t know what’s important to them until they lose it, which is why our philosophy in preserving the U.S. Embassy in Oslo was to keep as much of the physical building material as possible. But it was not possible to preserve the embassy’s fence through traditional preservation and architectural methods, because the landmarking authorities did not see its value and did not protect it by law.

In order to preserve the fence, I was faced with the problem of how to reveal its cultural value. As an artist, I could afford myself the license to experiment with ways that are unthinkable in normative preservation architecture, such as testing the limits of acceptable changes to the shape of the fence. I wanted to see how far I could change the fence and still have it be recognizable as a fence. Paradoxically, the more I transformed it, the more I was able to reveal the singular character of this particular fence. For example, I was only able to wield the straight bars the way I did because they were military-grade solid steel. Any conventional fence is made of hollow steel, and would have snapped in a thousand pieces under the massive torque that I applied to this fence. So, in the process of turning the fence into sculptures with unwieldy curves, I was able to show the weight, mass, and materiality of the fence. In other words, I revealed the fence’s cultural specificity, which is the basis upon which cultural value can be established, and upon which any case for preservation must rest.

What is the role that American modern art and architecture play in cultural diplomacy, especially in these fraught times?

Art and architecture bring people together and foster open-minded dialogue among different cultures, political views, and social backgrounds. This ability of art and architecture to convene exchange is what diplomacy is all about. Diplomacy is literally the art of the di-ploma, a word that comes from ancient Greek, meaning a bi-folded paper, the official folded letter that accredited the carrier as an ambassador. The word ambassador derives from the Latin ambactus, which means servant—someone who worked as a public servant engaged in international relations.

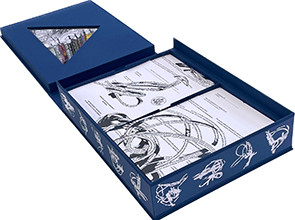

This idea that diplomacy has its origins in bi-folded papers inspired me to make an artist book to accompany Analogue Sites. The book, Treaties on De-Fences, is my version of a diplomatic pouch, containing 51 bi-folded prints, each one corresponding to one of the 51 sculptures I made from the fence of the U.S. Embassy in Oslo. Each bi-folded print is composed of straight lines of text taken from official treaties signed between the U.S. and Norway, which I transformed into the curving lines of the sculptures. The prints thus mirror the process of bending the straight solid steel bars of the fence into sculptures.

Each bi-folded print is an invitation to expand the diplomatic imagination and our creativity. The art of diplomacy is all about expanding the range of options toward, it is hoped, de-escalation and cooperation. Right now, there is great need for art that helps us visualize how to lower our guard and open up to one another. I hope my sculptures and my book allow people to experience that.

What other projects are you working on now?

I am immersed in exploring the intersection of art, architecture, and preservation through various initiatives, one of which is a digital guide to Analogue Sites that my team and I are creating in partnership with Bloomberg Philanthropies and the Fund for Park Avenue Sculpture Committee. The guide, which will be accessible via smartphones, aims to raise awareness of and advocate for the preservation of modernist U.S. embassies. It will feature interviews I conducted with, for example, Phyllis Lambert, who commissioned Mies van der Rohe to design and build the Seagram Building, and David Peterson, author of U.S. Embassies of The Cold War: The Architecture of Democracy, Diplomacy, and Defense.

What are you teaching this semester?

A PhD seminar on architectural fragments, with students from GSAPP as well as the Department of Art History and Archaeology. We are learning from history and encouraging ourselves to think differently and more intentionally about the future by examining what happened aesthetically, culturally, and politically when architectural fragments were moved from one place to another. And we are studying how architectural fragments can spark intercultural dialogue to initiate processes of repair, reparations, and reciprocity with communities.

Students are working on individual projects motivated by their passions for a particular architectural fragment. They are pushing the boundaries of what a fragment can be. One student, for instance, is working on pieces of architectural sounds. Another is looking at a whole façade. They are developing methodologies informed by art, architecture, preservation, and social science for identifying, documenting, preserving, and relocating architectural fragments. In doing so, they are discovering the importance of caring for existing things, and how such caring increases their agency in shaping the future.

What is special about teaching at GSAPP and in New York?

Teaching at GSAPP and being part of its vibrant academic community—which is woven into the cultural tapestry of New York City—offers endless inspiration and unparalleled opportunities for exploration and innovation. I encourage students to take full advantage of this privilege while they are here at Columbia. GSAPP is renowned for its experimental approach to architectural and preservation education. The school is a fertile ground for pushing the boundaries of practice. Within this dynamic environment, I direct the Preservation Technology Lab, where we engage in groundbreaking research involving art, technology, and heritage preservation.

We are in a moment of transition within the disciplines represented at GSAPP; we are turning toward a new ethic of care for the existing built environment, and leaving behind old models of architecture as extractive, speculative construction. New York itself serves as a laboratory for experimenting with how to care for the existing built environment and its eco-social complexity. The city is undergoing a massive adaptation of its building stock in light of climate change, which demands new research and creative thinking—which GSAPP is leading.