Professor Works on Projects at the Intersection of Race and Architecture

Mabel O. Wilson co-designed the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers and co-edited Race and Modern Architecture, among other things.

The architecture of Thomas Jefferson has been the focus of much of Professor Mabel O. Wilson’s work lately. The essay she contributed to the recently published book, Race and Modern Architecture—which she also co-edited—is on the buildings designed by America’s third president.

“Jefferson never reconciled those two sides of himself—his democratic ideals of freedom and equality and his position as a slave owner,” said Wilson, “and his architecture tells us this.”

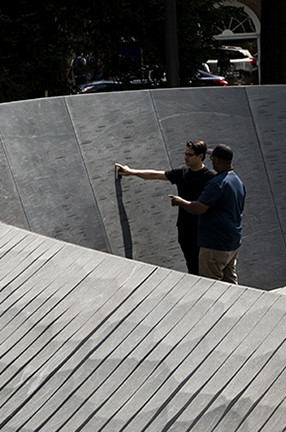

Wilson, who teaches at the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation and in the Department of African American and African Diasporic Studies, also co-designed the University of Virginia’s Memorial to Enslaved Laborers, which opened to the public in Charlottesville in April.

Columbia News caught up with Wilson recently to discuss these projects, as well as her involvement in an upcoming exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and what she’s teaching this semester.

Q. You have said that one of Jefferson's hallmarks as an architect was finding ways to hide places where slaves lived and worked, and that he understood that buildings make relationships between people. Did Jefferson use architecture to articulate human connections?

A. Jefferson deployed the architecture convention of the section—which is a vertical cut through a building, much like the plan is a horizontal cut through a building—to place the spaces where enslaved persons worked out of view. At his Virginia home, Monticello, which he designed just outside of Charlottesville, the dependencies—including the space where his concubine, Sally Hemings, lived—were buried below the walkway wings that connected to the main house. His placement of dumbwaiters near his fireplace made the work of Black servants invisible during intimate dinners.

In his designs for the University of Virginia, the kitchens and sleep areas of the enslaved were below the pavilions where faculty and their families lived, and the work yards were hidden behind the iconic serpentine walls. These architectural designs could be understood as encompassing a strategy of denial rather than reconciliation.

Q. In his New York Times piece about the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers, Holland Cotter said that "some of the most effective commemorative work of the past several decades has been formally abstract," citing, along with the UVA structure, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. Do you agree?

A. I think because of its prominence as a site of national commemoration, Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial transformed the architectural and artistic language of remembrance toward abstractions. Other artists and architects had used abstraction in memorials before Lin. Her use of spare, geometric form, sand materials proved an appropriate formal language to encapsulate the difficulties and injustices associated with the Vietnam War.

Q. What do you hope that visitors to the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers will take away from the experience?

A. I would like visitors to remember the enslaved as a community of friends and family, who sought dignity in life and the work they did. I also want visitors to comprehend the violence that made enslavement a reality, as noted in the memorial’s historical timeline, as well as in the “Memory Marks” that remember the 3,000 enslaved whose names we do not know. I hope they connect that to the ongoing fight for justice that drew so many into the streets over the past few months.

Q. Can you offer a preview of the MoMA exhibition, Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America, which opens on February 20, 2021?

A. The exhibition—which I co-curated with Sean Anderson and Ariele Dione-Krosnick, both MoMA curators in the department of architecture and design—brings together a remarkable group of 11 architects, designers, and artists. Their projects explore the architectural dimensions of Black space, which could be sites of resistance, refusal, and everyday life. The works also examine how the spaces of anti-Black racism—from slave quarters to redlining to mass incarceration—have shaped our built environment for well over 400 years. Our field guide—the exhibition catalogue that will be available when Reconstructions opens—expands those explorations with essay contributions from urbanists, activists, poets, writers, and scholars.

Q. What are you teaching this semester?

A. All of my classes are virtual. One is an upper-level, graduate architectural design studio. We are working with the Danspace Project at St. Mark’s Church in Manhattan's East Village to explore how performance artists have engaged in radical care practices. The students have been asked to design spaces of care in the aftermath of recent protests against police violence and the impact of the pandemic on communities of color.

I am also teaching the proseminar for undergraduates and graduate students in African American and African Diaspora Studies. We have thus far read W.E.B. Du Bois, Frantz Fanon, Toni Morrison, and Sylvia Wynter—timely reading about the practice of Black studies apropos these challenging times.

Q. Is it hard to keep students who are learning remotely engaged?

A. While not ideal on many levels (Zoom can be tiring on the eyes after several hours in a course like a design studio), the technology does make it easy to invite people from all over the world to join discussions with students. Overall, I’m finding attentive and engaged students wherever they are in the world.