Meet Valentina Izmirlieva, the New Director of the Harriman Institute

The war in Ukraine has affected every aspect of work at the institute, she says, including her plans for the Harriman's future.

Valentina Izmirlieva assumed her new role as director of the Harriman Institute on January 1, 2022. A longstanding member of the Harriman community, she has been a faculty member in Columbia’s Department of Slavic Languages since 1999. Her teaching ranges from Russian literature and culture, medieval literature of the Eastern Slavs, and the history of religion in Russia from Prince Vladimir to Vladimir Putin, to critical theory, gender studies, Slavic modernism, and Balkan cultural politics.

As a scholar, Izmirlieva has always aspired to expand the purview of her field beyond the Cold War logic that so often defines it. “All these places that are so culturally different—Central Europe, the Balkans, the Caucasus, Central Asia—are lumped in together with the Soviet Union and Russia, which provides only one context for understanding their distinctive histories,” she said, noting that she has devoted her entire career to researching other relevant contexts.

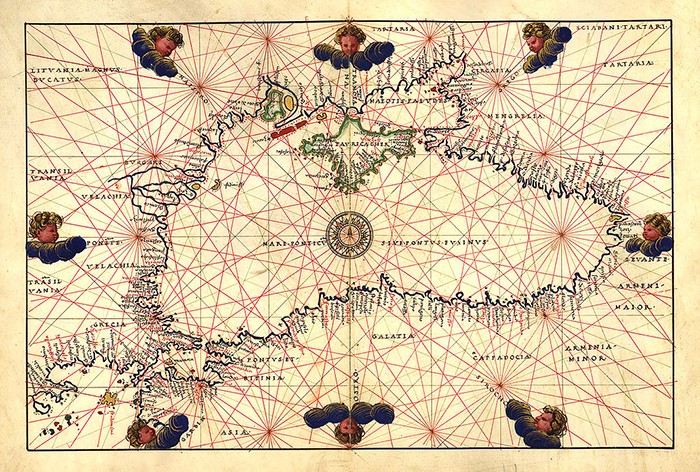

Izmirlieva’s ongoing project, Black Sea Networks, is a groundbreaking global initiative that anchors the Black Sea as a hub of cultural, political, and historical interest. The new framework it proposes aims to reorient Slavic studies from a shared Slavic identity imagined as homogenous toward shared spaces, where Slavs and non-Slavs are bound together by durable links of conflict and competition, cooperation, and creative compromise. “Shared lands are heavily contested, which makes land-based studies ideologically fraught,” she said. “Focusing on the sea de-centers the Slavic field in a way that reveals new heuristic advantages.” In 2016, the initiative won a two-year grant from the President’s Global Innovation Fund at Columbia.

Izmirlieva discusses the future of Harriman with Columbia News, as well as how the war in Ukraine has affected every aspect of the institute’s work.

Will you be introducing any big changes in terms of structure or programming at the Harriman Institute in the coming months?

I am the first humanities professor to lead the Harriman in over a decade, and part of my mandate is to bring back a more sustained focus on culture, religion, and the political power of imaginative work to the institute’s programming. I plan to build on existing programs, such as the Writers-in-Residence, in order to stake our claim as cultural brokers in the international arena, and expand our public outreach.

Over the last decade, our Writers-in-Residence program has brought to Columbia some of the most influential voices of Eastern European literature (Mikhail Shishkin, László Krasznohorkai, Dubravka Ugrešić, Maria Stepanova), and yet has fallen short in engaging larger audiences either at Columbia or, more broadly, in the literary New York world. In fall 2022, we will host the Bulgarian writer, Georgi Gospodinov, whose new novel, Time Shelter (due in English this month), has already made a big splash in Europe. Our next step will be a high-profile festival of contemporary East European literature, starring all five previous writers in residence. And that will be just the beginning.

Another priority is to build a program for environmental studies at the Harriman. The institute’s purview is a vast geopolitical region that stretches from Central Europe to Central Asia. Apart from being a region of key strategic and economic significance, it is also a zone of increasing environmental degradation and looming crises in food and water security, climate justice, and sustainability. And yet, those concerns have received little reflection so far in the Harriman’s curricula and programming. I am determined to remedy that.

The first step is to create an intellectual and institutional context for our environmental program by building broad lines of collaboration with the Climate School, the Society of Fellows and Heyman Center for the Humanities, and the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences. An incoming visiting professorship in the Environmental History of Eurasia, created with the support of the Climate School and Columbia Global Centers, and an international conference next year on the environmental effects of the war in Ukraine, will further help us lay the foundations of this new program.

My overarching goal is to increase the visibility and relevance of the Harriman Institute both within Columbia and globally. Building institutional partnerships within the university is a goal very dear to my heart, since I am a firm believer in the need for interdisciplinary dialogue. If you cannot communicate the hard-earned knowledge of your own discipline to others in a way that they can understand, your work is useless. But learning how to do this effectively is a slow, frustrating, and often thankless process.

Regional institutes like Harriman are explicitly built as spaces for public debate across disciplines, so we have a rare opportunity to foster interdisciplinarity at its best. My ambition is to expand the network of Harriman’s relationships to new partners at the University and, by engaging Columbia Global Centers, make our brilliant intellectual community a force of truly international significance. We call this new line of strategic engagement “Global Harriman.”

How has the war in Ukraine affected the Harriman?

This war certainly has affected every aspect of the work we do at the Harriman. It has challenged some of the foundational precepts of post-Soviet regional studies, and called for a serious conceptual and moral reckoning whose effects we are yet to see. As an established leader in this field, the Harriman community is uniquely positioned to shape the way we reconfigure our studies of the post-Soviet space under the new political reality, just as we did at the end of the Cold War in the 1990s.

During the past two and a half months, however, we have been responding to immediate needs. Following the Russian invasion on February 24, we prioritized helping students and colleagues at risk in Ukraine. To that end, I have worked hard to create a wide network of partnerships both within and outside of Columbia. And our work has begun to bear fruit. Together with the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and the Department of Slavic Languages, we offered an emergency fellowship for a Ukrainian graduate student who was in Kyiv when the war broke out. We are expanding the course offerings in our already strong Ukrainian Studies Program, and will host as a visiting professor in spring 2023, a political scientist from Kyiv, Volodymyr Kulyk.

We joined the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna and the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute in Cambridge to establish non-residential fellowships for Ukrainian colleagues, of which we are currently financing eight ourselves. More ambitiously still, in partnership with the Institute for Ideas and Imagination and Columbia Global Centers, we created three yearlong Harriman residencies in Paris for Ukrainian journalists, writers, and creative artists. Our goal is to launch a series of public-facing events in Paris and New York next year to amplify Ukrainian voices by highlighting the lasting contribution of Ukrainian culture to global society.

Anger and frustration about the war are palpable at the Harriman, especially among our MA students. We have found a productive way to channel this energy into practical work—a student-led initiative to create a digital archive of information on a variety of war-related topics. Since the early days of the war, a group of students has been working together with the news organization Eurasianet to gather, verify, and categorize the information that proliferates on social media, and to prepare a searchable, publicly accessible archival platform. Designed as a reference resource for journalists, human rights activists, experts, and scholars, this digital archive will launch its own website within weeks. Meanwhile, our new podcast, “Voices of Ukraine,” which tells stories of lives from our community upended by the war, has already made it into the top 10% global podcast ranking.

Will you continue teaching and working on your own research projects?

Teaching and advising students is the best part of my job at Columbia, so there is no way I will stop doing either. I just have to scale it down a bit during my tenure at the Harriman.

What is the current status of your ongoing project, Black Sea Networks?

It is still very much alive. In fact, the heuristic model it promotes has proved all the more relevant in the context of the war in Ukraine, which has emphasized anew the global strategic value of the Black Sea and its littoral. My initiative operates as a fluid system of research streams, and the “stream” that dominates our work right now focuses on an important moment in the history of the Black Sea after the Bolshevik Revolution: the Great Exodus across the Black Sea, from Crimea to Constantinople, when refugees from the disintegrated Russian Empire flooded the Ottoman capital for more than four years.

My team is currently preparing an exhibition at Pera Museum in Istanbul, which will explore the cultural encounters between the refugees and the city, and the ways in which guests and hosts influenced one another. I am also preparing the first anthology in any language specifically dedicated to these cultural encounters.

When will your book about Balkan Christian hajjis of the Ottoman Empire and their role in building Slavic national elites be finished?

To be honest, I much prefer the process of solving a puzzle to publishing the result. The beauty of research is that each puzzle solved opens the way to new ones and, in that sense, each project is unfinishable. We just have to arbitrarily draw the line somewhere, and round it out in a way that makes aesthetic sense by giving the impression of closure.

I have rewritten my book twice already in the last 10 years, each time because I came across new data that turned my old assumptions on their heads. It has been great fun, and I probably can keep doing this for another 10 years. But there are other things I want to write about as well, so it is time to wrap it up. I keep telling myself that I will finish it when the war is over. One more reason to hope for peace soon!