Can America Restore Its Trust in Government?

Many Americans no longer believe that government works for them. A new book explores how we need to fundamentally change our institutions to restore faith in them.

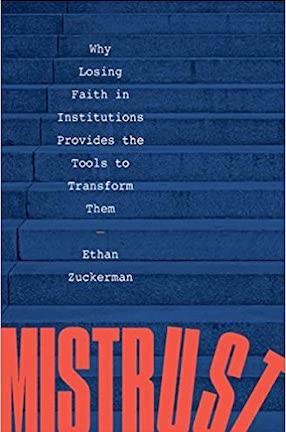

America is a nation of insurrectionists. In his book, Mistrust: Why Losing Faith in Institutions Provides the Tools to Transform Them, Ethan Zuckerman, a senior visiting research scholar at the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, writes, “A nation formed through revolution must recognize that rebellion is an essential aspect of its character and its destiny.”

Governing a nation of rebels is a formidable balancing act. For much of America's history, our country has been capable of adapting to its citizens’ desires for individual rights while effectively governing. However, recent bitter partisanship has often incapacitated our institutions, making many Americans question their purpose.

Columbia News caught up with Zuckerman to find out why our country deeply distrusts government and how a new generation of activists might radically change our systems to create a more just society that works for more Americans.

Q: In your introduction you state, “I write this book at a moment when it feels like America might snap.” What made you think, very presciently, that “America might snap”?

A: I worked with colleagues at MIT and Harvard to understand what happened in American media around the 2016 election and became convinced that Americans were starting to encounter two incompatible media universes, and as a result, began advocating for thoroughly incompatible visions of the country. Once Donald Trump came into office, he did something that I hadn't expected—he worked to make the divides between right and left, between those incompatible realities, even starker. Unfortunately, the divisions around the 2020 election, the misinformation around Trump's claims of victory and even the violence seemed all too likely, even four years back.

Q: What inspired you to write Mistrust?

A: I spent nine years running a lab at MIT called the Center for Civic Media. In the process, I met lots of young activists, people thoughtful about ways they might change the world. I found that very few of them believed they would be most effective by working through conventional civic means—electing candidates for office, helping those candidates shape and pass legislation. Instead, they were exploring different ways of having an impact, through protest, through changing culture, through pressuring institutions directly. I decided that I wanted to understand whether these other paths to civic efficacy were actually effective, and what caused so many of these smart people to have low confidence in conventional civics in the first place. That quickly led me to studying mistrust, which is a major factor underlying our contemporary political and civic system.

Q: You note that America almost from its inception was a country filled with insurrectionists, and the only reason that we haven’t had perpetual revolutions is that in the past, our government has adapted to the changing needs of its citizens. What happened to our government in recent years that has made it unable to adapt?

A: Institutions naturally calcify. At first, we don't know how institutions should do something, like hold a Presidential election. Then we try something out and end up with a solution: we should vote on a Tuesday in November, so that planting and harvesting were done, and so that people who were in church on Sunday could travel to town on Monday and vote on Tuesday. While that made sense two hundred years ago, it makes much less sense now. But tradition has incredible power, and people often find ways to gain power by taking advantage of the ways institutions currently work. Changing an institution involves more than demonstrating that an institution no longer works well, it involves finding a way to persuade the people whose power will be challenged by changing the institution that the benefits of the change outweigh the power they lose in the process.

Q: How can we regain trust in institutions and in our fellow citizens? How does our country move forward?

A: We have surprisingly good trust in each other, even at fairly high moments of polarization. Americans rank in the middle of nations in terms of trusting fellow citizens, even if we rank quite low in trusting institutions. As for regaining trust in institutions, I don't think it's as simple as that. I actually think many institutions cannot and should not increase in trust unless we see an ongoing effort for those institutions to change and to involve citizens in making those changes. The answer is not a PR campaign on trusting American institutions again; it's actually looking at badly broken institutions like policing and prisons, abolishing the broken ones and creating new community safety institutions in their place.

Q: Now that you’ve finished writing your book, hopefully you have time to read for pleasure. What’s on your list of books to read, and why did you choose them?

A: I do a lot of listening, because I like working with my hands, such as doing woodworking and welding. I've been on a kick lately listening to older literature that's now in the public domain. I just listened to The Great Gatsby and marveled at just how well-written it was and what a compelling and disturbing picture it drew of wealth in the Gilded Age. I'm looking for more from that period about a hundred years back, as parallels in levels of inequality feel worth exploring right now.

Q: Imagine in a post-COVID world, you’re hosting a dinner party. Which three scholars, authors, activists, artists, or even celebrities, dead or alive, do you invite and why?

A: Ibram Kendi, who's done such important work on introducing the idea of anti-racism, actively combatting broken structures that are damaging for all Americans, not just people of color. Tarana Burke, who started the #MeToo movement years before celebrities and others picked it up. And Greta Thunberg, whose energy and focus are both inspiring and a little bit terrifying.

Check out Books to learn more about publications by Columbia professors.