After a Friend Dies, a Professor Helps to Finish Her Book

Rachel Adams honors a colleague by working on “Unexpected,” a book about motherhood, prenatal testing, and disability.

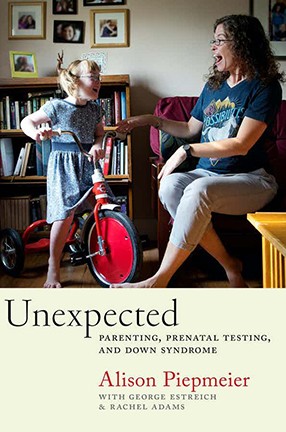

When Professor Alison Piepmeier died of cancer several years ago, she left behind not only her 8-year-old daughter, Maybelle, who has Down syndrome, but also an unfinished book about motherhood, prenatal testing, and disability.

In Unexpected, Professor Rachel Adams, who teaches in the Department of English and Comparative Literature, and George Estreich pick up where their friend and colleague Piepmeier left off, honoring her research, as well as adding new perspectives to her work.

Based on interviews with parents of children with Down syndrome, along with women who terminated their pregnancies because their fetus was identified as having the condition, Unexpected gives a nuanced view of reproductive choice today. At a time when medical technology is rapidly advancing, the book also focuses on the complex, frequently troubling understanding of Down syndrome and prenatal testing.

Adams speaks with Columbia News about the challenges of taking on the completion of Unexpected, as well as her favorite book that no one else has heard of, which books she loved most as a child, and her continuing innovations in the classroom as online learning continues.

Q. How did you become involved with this book?

A. Alison Piepmeier was a dear friend, who I knew as a professor in English/Women and Gender Studies at the College of Charleston in South Carolina, as well as a fellow parent of a child with Down syndrome. Our children with the condition, my son, Henry and her daughter, Maybelle, were a year apart in age, and we first met when Maybelle was about one.

For most of the time I knew her, Alison had a brain tumor that eventually took her life in 2016. A few months before she died, she asked that I finish her book, along with our mutual friend, the writer George Estreich.

The work George and I did on the book involved extensive editing, revising, and reorganization of Alison’s unfinished manuscript, as well as coauthoring the introduction and writing one additional chapter each. Our biggest challenge was to balance honoring Alison’s wishes and (to the best of our knowledge) intentions, with creating the best possible book from the fragments she left us.

Q. What are some of the ways in which Down syndrome is misunderstood and stigmatized, particularly in the context of prenatal testing?

A. Because Down syndrome is one of the most common and easily detectable prenatal genetic disabilities, it tends to be a focus of prenatal testing and research. This has perpetuated misconceptions about Down syndrome by implying that it is akin to such lethal genetic conditions as Tay Sachs and Trisomies 13 and 18. People tend to think that if there is a test to identify Down syndrome before birth, it must be very bad and possibly incompatible with life, involving pain, suffering, and a shortened life span.

In truth, Down syndrome is a spectrum disorder, and its manifestations can’t be predicted by a prenatal test. The condition itself does not cause pain and suffering, and people who have it can lead long, full lives. Ironically, alongside the emergence of prenatal testing regimes, healthcare for those with Down syndrome has improved, dramatically extending the duration and quality of their lives.

Q. How have things changed since Henry was born in terms of disability rights and reproductive choice?

A. Things have certainly been worsened by the commercialization of prenatal testing. There is even a test called MaternitiT21, as if the sole purpose of prenatal testing is to ferret out Down syndrome. Moreover, conservative politicians in several states have used Down syndrome as an excuse to curtail women’s access to abortion by introducing, and in some cases successfully passing, laws that make it illegal to terminate a pregnancy because of a prenatal diagnosis.

Despite all the bad news, this is probably the best time in history for a person with Down syndrome to be alive. Knowledge about best practices for educating people with Down syndrome has advanced a great deal. As with healthcare, many people don’t have access to good, inclusive education, but if you go to the right school, there is a wealth of understanding about how to best accommodate students with DS and help them fulfill their educational potential. There is also greater acceptance and visibility of people with Down syndrome in the social world. Henry has appeared in a Toys R Us catalog, on local and national news, and on Sesame Street, and he will participate in his first fashion show this spring!

Q. What books do you recommend for getting through the pandemic winter?

I’m teaching a class on pandemic works, so my reading has been more in the mode of diving in than escaping from. But there are some truly wonderful novels about pandemics: Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel, Severance by Ling Ma, and Zone One by Colson Whitehead. I also loved The Great Believers by Rebecca Makkai, which is about the AIDS epidemic. Over the summer, I reread Hilary Mantel’s brilliant Henry VIII trilogy, which was perfect late-Trump era fare.

Q. Any others on your reading list?

A. Last fall I taught a class on comics and health, which I ended with a huge reading list. On my bedside are three graphic narratives that come highly recommended: Glyn Dillon’s The Nao of Brown, Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina, and Emil Ferris’s My Favorite Thing is Monsters.

Q. What's your favorite book that no one else has heard of?

A. A friend gave me Kevin Wilson’s Nothing to See Here, which I read just as we were descending into the pandemic last March. I thought it was moving and brilliant. Nobody else I know has heard of it.

Q. What were some of your favorite childhood books, and which ones do your children enjoy?

A. Given the work that I do now, it’s not surprising that many of my favorites involved misfits and outsiders, as well as stories about illness, disability, and science gone awry: Robert C. O’Brien’s Mrs. Frisbee and the Rats of Nimh, Roald Dahl’s James and the Giant Peach (really anything by Dahl, so dark and mean-spirited!), and Norton Juster’s The Phantom Tollbooth.

My older son is reading The Odyssey for his English class, which has been fun since I also taught it in Lit Hum this fall. Other books we’ve enjoyed together: Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime, Dear Evan Hansen (Val Emmich et al), Benjamin Sáenz’s Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe, and Jacqueline Woodson’s Brown Girl Dreaming. When my kids were younger, they loved anything by Mo Willems or Arnold Lobel (I especially enjoyed Owl at Home).

Q. What are you teaching this term? How are you helping your students cope with online learning?

A. Lit Hum, spring semester and Medical Humanities: Pandemic and Social Inequality. The way I’m coping with online learning is to try to get to know my students as much as possible. I make them do multiple self-introductions, and have them write a lot about their own lives and feelings, as well as (or in relation to) the course material. I try to spend time in office hours asking about their lives and the stuff in the backgrounds of their Zoom screens. All of this is intended to combat the impersonality and distance of Zoom. I also encourage similar dynamics among my students. I like it when they talk to each other over chat, and I have them working in groups a lot.

My innovation for this semester was to apply for a Course Enhancement Grant to bring an artist and a designer for workshop classes in the medical humanities course. Whit Taylor writes comics that are often about race and healthcare. Sara Hendren is a professor of design and engineering, who studies disability and material culture. Each will visit our class by Zoom for a two-hour session of active learning. I think this will break up the tedium of Zoom, and give me some fresh ideas for my own teaching in the future.

Q. You're hosting a dinner party. Which three academics or scholars, dead or alive, would you invite and why?

A. I am a shy person and often intimidated by people I admire from afar. So I’m going to go for something intimate and comfortable, three professors who teach and write about disability, and are also the mothers of people with Down syndrome: Alison Piepmeier, Sara Hendren, and Janet Lyon. And we would have repeated toasts to my coauthor, George Estreich.

Check out Books to learn more about publications by Columbia professors.