‘Partisans of the Nude’ Opens at the Wallach Art Gallery

The exhibition is a survey of genre art of the nude made by artists in areas that were formerly Ottoman, but not yet Arab.

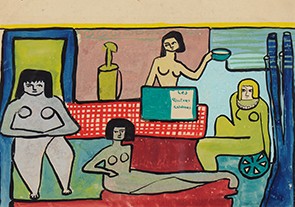

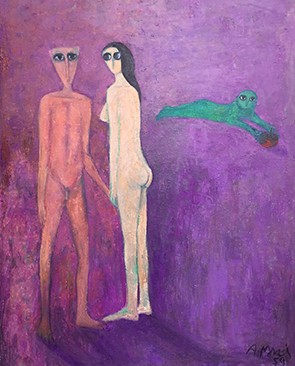

Partisans of the Nude: An Arab Art Genre in an Era of Contest, 1920-1960 is now open at the Wallach Art Gallery, and will remain on view until January 14, 2024. The exhibition presents a survey of genre art of the nude made by artists in areas that were formerly Ottoman, but not yet Arab. It is the first comprehensive survey of such works in the United States. Kirsten Scheid (CC ’92), a professor of anthropology and art studies at the American University of Beirut, who is a visiting professor in the Department of Art History and Archaeology this semester, curated the exhibition.

Partisans of the Nude comprises more than 50 paintings and 20 drawings, as well as sculptures and reliefs, photographs, film, and ephemera. The makers of these works range from internationally recognized artists credited with founding Arab art schools, such as Saloua Raouda Choucair, Jewad Selim, Kahlil Gibran, and Kamel Telmisany, to little-known and yet-to-be-studied artists, intellectuals, and critic-activists.

Although the nude genre has been recognized as foundational to Western art since ancient Greece, the role the nude played in carving out an Arab art has been ignored by both nationalist histories and Orientalist narratives. The Wallach exhibition shows that art movements outside the West created their own modernity through the nude genre. Though often spoken of as taboo and practically absent from Arab art production, the nude was important for early- 20th-century artists who sought to define their societies as post-Ottoman and cosmopolitan. Partisans of the Nude argues for new ways of thinking about the formation of modern Arab and Muslim artists and audiences. The exhibition was made possible in part by the Barjeel Art Foundation.

Scheid discusses the exhibition and what she’s teaching at the University this semester with Columbia News.

How did your involvement with Partisans of the Nude come about?

When I started my ethnographic fieldwork in Lebanon in 1997, studying the relationship between contemporary art and national reconstruction projects, many people actively involved with visual arts—gallerists, collectors, even artists themselves—told me to return to New York. New York, they said, has art; Beirut, no. I was puzzled: We were amid loads of art, with gallery openings every other week. People helped me understand that, from their perspective, all of that activity was new and not local, “because as Arabs, as people from the Middle East, they couldn’t draw on a home-grown history of art, which starts with life drawing.” Telling me that nudes “have always been proscribed in their region,” they explained their current artistic creativity as exceptional.

The exceptionality made sense to me: All the artists I had learned about at Columbia were remembered for their exceptionality, in some way or another. What didn’t make sense were the painted or sculpted nudes that I kept coming across in people’s homes, and, especially, in newspapers published decades earlier. I chose to study the history of this no-history, this absented or self-absenting art, and the nudes made up a prominent chapter. Many families who were the descendants of artists helped me focus on this research in Lebanon. Later, the research expanded, with the help of numerous colleagues in art history and anthropology, to examine the genre in other modern Arab countries, to inquire into the importance of the nude in defining “Arabness,” between the end of the Ottoman Sultanate in 1922 and the founding of the new Arab nation-states with which we are familiar today.

The name of the exhibition, Partisans of the Nude, comes from the name for a nudist movement that Palestinians, Lebanese, and Turks embraced in the 1930s. Studying this artwork introduced me to a deeply interconnected set of intellectual, aesthetic, and political projects. For example, proponents of nudism recommended viewing the nudes on public display to practice the moral transparency, self-awareness, self-reliance, and forthrightness deemed necessary to counter corruption and aged customs. The artwork also connected to a kind of literature, al-adab al-`ury, that was said to be similarly bracing.

Every time I share this material, I learn more from it. My new book, Fantasmic Objects: Art and Sociality from Lebanon, 1920-1950, devotes a chapter to nudes. The four-dimensional format of an exhibition, however, allows audiences to encounter the nude genre in life scale, to experience their visceral reactions, and to wonder at why they could ever be content to look only at grand French nudes.

How did the nude genre help define a modern Islamic identity and practice for Arab citizens-to-be?

This aspect of the Arab nude genre had completely escaped my attention at the beginning of my research into the paintings and sculptures that were made mostly between 1910 and 1950. It was only when sympathetic viewers worried that “fanatics” or “Muslims” would sabotage an exhibition of these nudes that I began to reckon with the piety practiced by their makers as Muslims.

If you set aside the framework that associates modernism with secularism, you start to observe in the writings, lectures, and, especially, the artworks themselves signs of an active, if explorative, devotion. For example, landscapes that otherwise resemble charming French paysages reveal a saturation with signs (ayat) of a divine creator (from mundane foliage to majestic mountains and dancing sunrays) in place of the Impressionists’ signature brushwork.

Likewise, nudes could channel celestial wisdom and remind the pious of their place in a grander scheme. Their makers declared themselves modern Muslims and also differentiated themselves from the Ottoman rulers, who were accused of decadence and lasciviousness. Importantly, for artists born as Muslim Ottoman subjects (and not unlike their Christian-professing counterparts), in the wake of the Islamic caliphate’s abolition in 1924 (following the abdication of the Ottoman Sultan), nudes bespoke a direct connection to divinity. Neither religious denomination nor indigenous identity circumscribed the nude, making it an exercise in cosmopolitanism.

If official European art academies tended to prohibit official enrollment by non-Europeans (as well as female Europeans), they could not prevent excluded people from study in night schools, affiliating themselves to a universal art historical legacy, and commandeering it to populate Arab Tunisian, Egyptian, or Bahraini history paintings. Interestingly, whereas art history tends to treat life drawings as classroom exercises, modern Muslim (and non-Muslim) citizens-to-be often painted up their sketches. They offered these straightforward displays of professional competence to their would-be compatriots at heavily promoted public exhibitions, so others could experience as they had that reflexive proximity to divinity.

What are you teaching at Columbia this semester?

To my delight, a graduate seminar, Modernity by Art: Materiality, Imagination, and Convergence, which introduces students to epistemological and methodological questions about modernity, community, and artistic practice through case studies from the Middle East (particularly, Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Iraq, Iran, Egypt, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Turkey). The course bridges art history and anthropology to examine the material and imaginative ways that post-Ottoman, anti-colonial communities produced the modern, experienced it, and became progenitors of it, yet often from the outside. What new types of community, identity, economy, and spirituality did artists proffer? How do these relate to the maps, timelines, and categories we rely on to understand globalization and the contemporary today? What obstacles did artists face in their projects for social relevance, and what new entanglements did their negotiations create?

I say, “to my delight,” because, 30 years ago, such questions were discouraged when I majored in art history here. Back then, my insistence on thinking about society through art, and seeing art as an agent making society, received scorn from my esteemed professors. Now, by putting students in touch with original, newly translated newspaper essays, manifestos, unpublished manuscripts, and non-canonical artwork, I hope to prompt discussions of how we think about modernity cross-culturally. My hope is that the course will also encourage students to reflect on what modernity and art mean to them, and how they locate themselves in our unequally shared political world.