Pulitzer Prizes Celebrate 100 Newsworthy Years

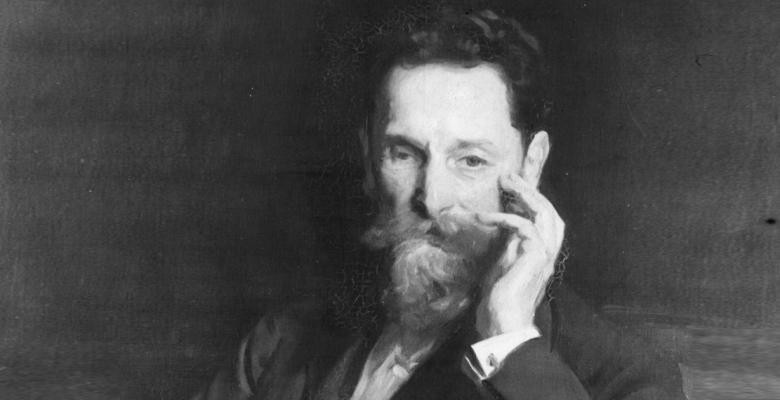

When newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer contacted Columbia with a notion about founding a journalism school in 1892, the trustees turned him down. Journalism was not quite respectable at the time, and Pulitzer owned the often-sensational New York World, whose muckraking stories and yellow-tinged comics gave rise to the derogatory phrase “yellow journalism.”

A decade later Pulitzer tried again, with more specific plans for a journalism school and annual prizes to reward the best work. “My idea is to recognize that journalism is, or ought to be, one of the great and intellectual professions,” Pulitzer said, according to a 2010 biography by James McGrath Morris. He also proffered a $2 million gift at a time when Columbia’s operating budget was a third of that.

The Journalism School opened in 1912, a year after Pulitzer’s death, and the first prizes were awarded in 1916. (Although housed at Columbia, the prizes are run independently from the school.)

This year marks the centennial of the prizes, the best known and most highly respected awards in journalism. The Pulitzer Prize board kicked off a yearlong commemoration on Jan. 28 with a party at the Newseum in Washington, D.C., attended by hundreds of prizewinners. More events are planned throughout the year, from multi-day seminars on such topics as social justice and the presidency to smaller “campfire” events in at least 46 states. This year’s awards will be announced in April.

“Journalism is changing rapidly, and the Pulitzer Prize board is doing its best to embrace the changes and adapt to them,” said Mike Pride, administrator of the prizes. “In both journalism and letters and music, the quality of what wins remains high while the diversity of who wins is richer than ever.”

The centennial is an opportunity to chart the myriad changes in journalism since 1916. The first prizes went to two newspapers and two books, but Pulitzer was prescient enough to include a provision in his will that allowed the prizes to adapt to changes in culture and technology.

Today’s 21 categories include drama, photography, poetry and music. With the new digital century, online newspaper content became eligible in 2006 and online only news organizations in 2009. This year, five prize categories were open to magazines. Whatever the format, the quality of the journalism is what stands out

Image Carousel with 5 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

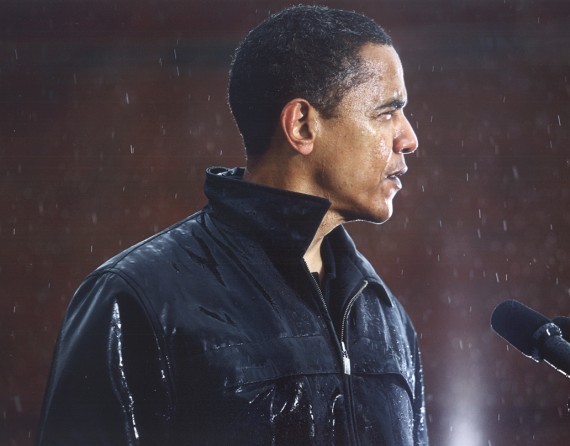

Slide 1: Damon Winter (CC’97) was awarded the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for feature photography for his pictures of Barack Obama (CC’83) on the presidential campaign trail. Photo by Damon Winter

-

Slide 2: This iconic picture of Marines raising the American flag after capturing Iwo Jima won the 1945 Pulitzer for breaking news photography. Photo by Joe Rosenthal

-

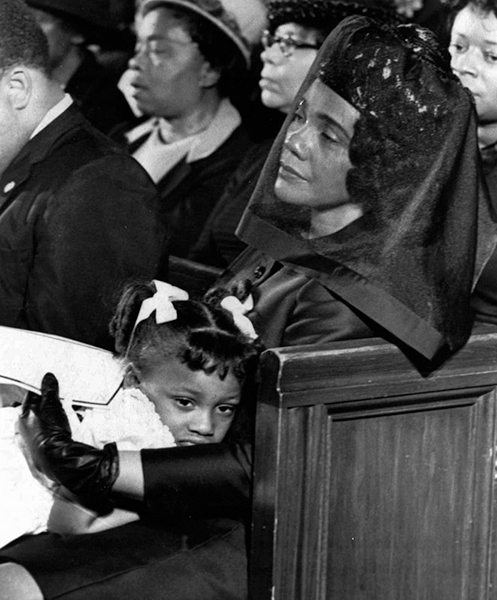

Slide 3: This photo of Coretta Scott King at the funeral of her husband, Martin Luther King Jr., won the 1969 Pulitzer Prize for feature photography. Photo by Moneta J. Sleet, Jr.

-

Slide 4: President John F. Kennedy and former president Dwight D. Eisenhower walk through Camp David together, a photograph that won the 1962 Pulitzer Prize. Historians say they were discussing the failed Bay of Pigs invasion. Photo by Paul Vathis

-

Slide 5: Rebel soldiers hold their position in the Syrian city of Aleppo, a picture that won the feature photography Pulitzer in 2013. Photo by Javier Manzano

Damon Winter (CC’97) was awarded the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for feature photography for his pictures of Barack Obama (CC’83) on the presidential campaign trail. Photo by Damon Winter

This iconic picture of Marines raising the American flag after capturing Iwo Jima won the 1945 Pulitzer for breaking news photography. Photo by Joe Rosenthal

This photo of Coretta Scott King at the funeral of her husband, Martin Luther King Jr., won the 1969 Pulitzer Prize for feature photography. Photo by Moneta J. Sleet, Jr.

President John F. Kennedy and former president Dwight D. Eisenhower walk through Camp David together, a photograph that won the 1962 Pulitzer Prize. Historians say they were discussing the failed Bay of Pigs invasion. Photo by Paul Vathis

Rebel soldiers hold their position in the Syrian city of Aleppo, a picture that won the feature photography Pulitzer in 2013. Photo by Javier Manzano

“It’s one of the special things about Columbia that we’re not only home to the world’s best journalism school, but also to the most iconic prize in journalism, arts and letters,” said University President Lee C. Bollinger, who has been on the Pulitzer Prize board since becoming president of the University in 2002. “It’s a privilege for me to participate in the Pulitzer board’s very thoughtful deliberations aimed at recognizing the commitment to creative excellence and public service. And of course, it’s just a delight to be able to hand out the prizes each year here on campus.”

The stories that win can change the course of history. Consider The Washington Post’s coverage of a break-in at Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate office complex that ultimately led to a president’s resignation; or The New York Times’ publication of the secret government history of the Vietnam War, the Pentagon Papers; or The Boston Globe stories on how the local diocese moved pedophile priests from one parish to the next, a scandal that engulfed the Roman Catholic Church and became the subject of the Oscar nominated film Spotlight. All three papers won the Pulitzer for public service.

“These kinds of stories offer a panorama of not just journalism’s power from year to year but of U.S. history,” said Roy J. Harris Jr., author of Pulitzer’s Gold: A Century of Public Service Journalism (Columbia University Press).

Pulitzer Prize-winning stories can also save lives, change social mores and quell fears. The 2014 prize for public service went to the Charleston, S.C. Post and Courier for stories on how the state’s lax laws on domestic violence led to hundreds of deaths. After the series ran, the legislature drafted reforms to the state’s domestic violence laws.

Breaking standard journalistic practice, The Des Moines Register in 1991 printed the name of a rape victim, at her request, to put a face on an underreported crime. And in 1985, The Denver Post found that most missing children are runaways or involved in custody disputes, not victims of kidnapping or murder.

“The stories that win Pulitzers are an early warning system of what’s on people’s minds,” said Andie Tucher, a professor at the journalism school who specializes in the history of journalism.

At least six Pulitzers went to stories exposing the Ku Klux Klan. In 1921, the now defunct Boston Post published a hard-hitting series on the financial dealings of a schemer named Charles Ponzi. He was arrested as a result, his name forever a synonym for fraud. Winning stories in the 1950s covered desegregation.

“The public service award often goes to smaller newspapers that are covering stories that are terribly important to their communities,” said Tucher. “It is a way for the Pulitzer board to say, ‘You’re doing what great journalism should do.’”