Researching the Oceans, From the Gulf of Mexico to Madagascar

Kailani Acosta is curating an exhibition that explores how geology, history, and culture intersect and influence each other.

Notebook is a Columbia News series that highlights just some of the many fascinating students who study at our University.

Kailani Acosta, who is graduating with a PhD in Earth and Environmental Sciences this winter, has travelled the world—as far as Madagascar—for her research on nutrient cycles in the ocean. On February 9, an exhibition that she curated that explores the interconnectivity of geology, race, agriculture, and marine biology will open for one night only at Persona Studio in Brooklyn (Acosta hopes the exhibition will have a longer life at another venue soon). Columbia News spoke with Acosta about her research, the connections between ecology and history, and what she does in her spare time.

What brought you to the PhD program in Earth and Environmental Sciences, and why did you want to do it at Columbia?

After I graduated from undergrad at Brown, I worked in environmental consulting in New York City. The parts I loved most about my job were conducting research, being out in the field, and putting together analyses. I decided that I really wanted to focus on that by pursuing a PhD, and I loved living in the city. I knew I wanted to be in New York because I grew up on Long Island and my family and friends are so close.

I have always been the kind of person that asks a ton of questions. I always want to know how things work and how we can understand the world better. The ocean has been a place of mystery and serenity for me, and I wanted to understand more about it in order to understand the world.

Your research focuses on the role of phosphorus and nitrogen in the upper ocean in the Northern Gulf of Mexico. Why are those two elements important to understand, and what drew you to focus on that region in particular?

Understanding nutrient cycling is essential to understanding the basis of ecosystems everywhere. Nitrogen and phosphorus are two of the most important nutrients for life and growth both on land and in the ocean. Studying how these nutrients change over time, and spatially, from the coast to offshore regions is crucial to understanding how life and biology change in the Gulf of Mexico, too.

The Gulf of Mexico is an interesting study region because it is the confluence of two extremely different ecosystems: the freshwater Mississippi River system and the marine Gulf of Mexico. The Mississippi River basin has been greatly impacted by nutrient addition from agriculture (fertilizers and pesticides have lots of nitrogen and phosphorus), industry, sewage treatment, and other anthropogenic sources. On the other side, the marine Gulf of Mexico has a lot lower concentrations of nutrients, different biology, and strong currents and physical drivers. The intersection of physical, chemical, and biological factors in this region makes it really exciting to study.

What's the farthest (and perhaps most interesting) place your research has taken you?

Apart from my Gulf of Mexico research, my favorite place that I've worked is Nosy Be, Madagascar. I lived there and worked at the National Center for Oceanographic Research. We did a variety of amazing work, from studying coral reef health to creating an environmental education program in the remote areas of the island.

Tell us about your exhibition. How did it come together, and what kind of works are you showing?

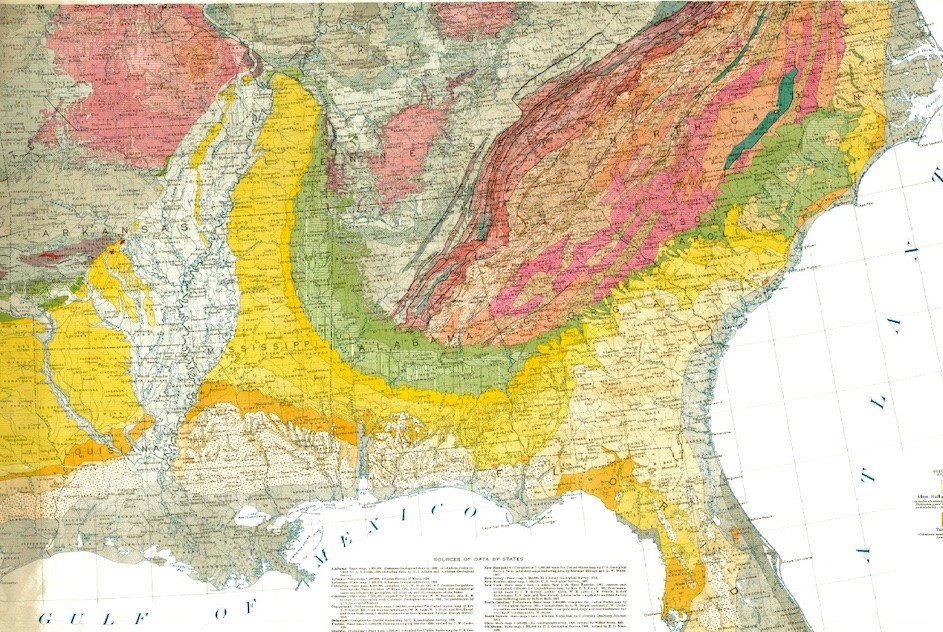

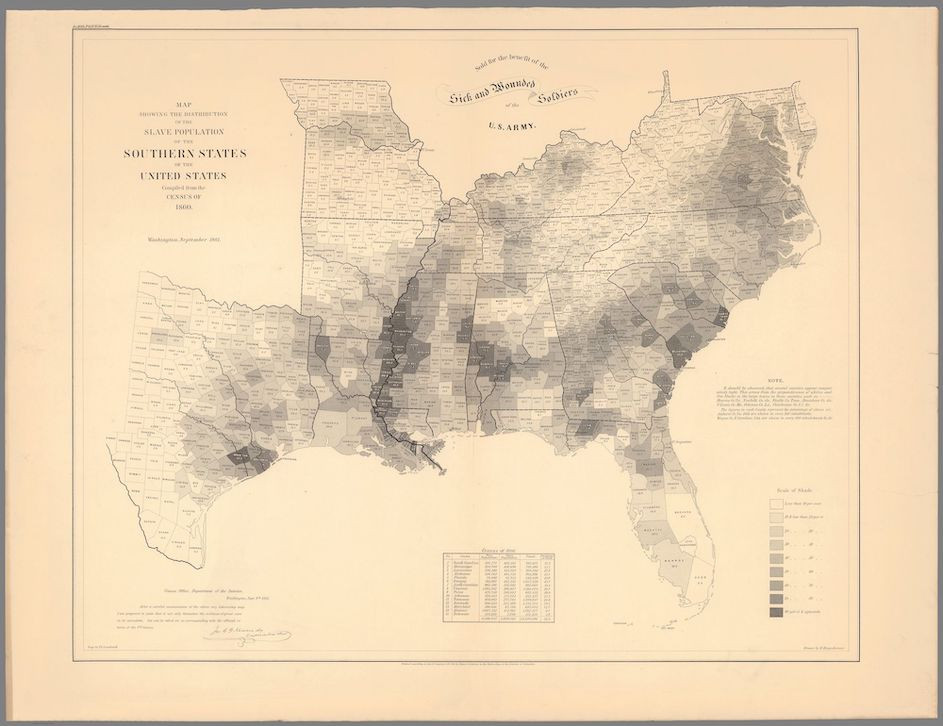

Throughout my PhD, I’ve gotten questions about how my diversity work connects to my science. Most scientists are not often faced with connecting their background to their research or to science writ large. As a woman of color in science, it’s something I think about frequently. I wanted to create something that visually shows these connections between geology, biology, race, and culture. The goal of the exhibition is to connect how fundamentally intertwined race, culture, marine biology, and geology are through large-scale, artistic visualizations of maps. The exhibition is a curated selection of authentic old maps that I found from the Columbia archives; current maps and figures; and other physical samples like rocks and phytoplankton cultures that show the recurrence of the same pattern geologically, physically, and culturally.

One map in the exhibition, for example, shows the Black Belt, the crescent-shaped belt of fertile soils that runs through Alabama, Mississippi, and much of the South. This fertile soil was created from the weathering of rocks made of ancient marine phytoplankton from 100 million years ago, and subsequent organic matter accrual. The soil has influenced where and how agriculture is done, the proliferation of slavery in the South, tribal removal, and current patterns of race, culture, poverty, economic status, and education. The exhibition will show how those ancient phytoplankton connect to the world we live in today.

Do you have any favorite places to eat in New York City that our readers should know about?

My favorite places are Thai Villa, La Flor de Broadway, and of course, Absolute Bagels.

Do you have any favorite city activities that have nothing to do with your work?

My favorite things to do are going on walks with my dog in the park when the sun is about to go down, playing softball with my team in Williamsburg, and thrifting with a specific mission.