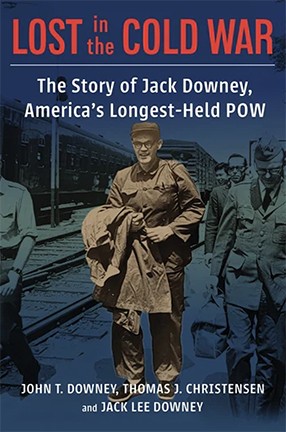

The Story of Jack Downey, America’s Longest-Held Prisoner of War, Comes to Light

Professor Thomas Christensen explores the international politics of the Cold War and U.S.-China relations in a new book.

In 1952, John T. “Jack” Downey, a 23-year-old CIA officer from Connecticut, was shot down over Manchuria during the Korean War. The pilots died in the crash, but Downey and his partner, Richard Fecteau, were captured by the Chinese. For the next 20 years, they were harshly interrogated, put through show trials, held in solitary confinement, placed in reeducation camps, and toured around China as political pawns. Other prisoners of war came and went, but Downey and Fecteau’s release hinged on the U.S. acknowledging their status as CIA assets. Not until Nixon’s 1971 visit to China did Sino-American relations thaw enough to secure Fecteau’s release, also in 1971, and Downey’s in 1973.

Lost in the Cold War is the never-before-told story of Downey’s decades as a prisoner of war and the efforts to bring him home. His memoir—written in secret late in life—interweaves deprivation with humor and the absurdities of captivity. Through the eyes of his captors and during his tours around China, Downey witnessed the Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution, and the drastic transformations of the Mao era.

In interspersed chapters, Thomas Christensen, the James T. Shotwell Professor of International Relations at Columbia SIPA, and an expert on Sino-American relations, explores the international politics of the Cold War, and tells the story of how Downey and Fecteau’s families, the CIA, the U.S. State Department, and successive presidential administrations worked to secure their release.

Christensen talks about the book with Columbia News, as well as how a page-turner allowed him to extend a recent trip to Norway, and the ideal guest list for his next dinner party.

How did this book come about?

After the hero of the book, Jack Downey, passed away, his family found a memoir that he had written in secret. He left a note saying that he wanted the memoir published at an academic press. The family contacted Stephen Wesley, an editor at Columbia University Press, where I edit a series of books, the Nancy Bernkopf Tucker and Warren I. Cohen series on America in Asia.

Stephen asked me to read the memoir for consideration for publication in the series. I found the memoir impressive and moving, but initially rejected it on the grounds that, on its own, it was not scholarly. I suggested that it be published at a trade press. I was then asked if I could think of any way to publish the memoir at Columbia, as this was Downey’s strong desire.

My solution: A diplomatic historian could write accompanying chapters inserted into the memoir to analyze the international and domestic context of Downey’s story. This would involve intensive research in Chinese and American primary and secondary sources, which would qualify the book for review at a refereed academic press. I offered Stephen and the Downey family a list of several diplomatic historians.

I am a political scientist and, though I have written books that involve a lot of historical work with archival materials, I did not include myself on the list of diplomatic historians. The family liked my solution, but they asked me to write the analytic chapters, and suggested that Downey’s son could write the afterword about his father’s life after his release by the Chinese. I had just started a different project, but I could not refuse after reading Downey’s memoir. Most important, when I explained the situation to my two children, they said that I had to say yes because I owed it to the hero and his family. So I did, and I am very glad I made that decision.

What do you think were the key qualities—mental, spiritual, physical—that enabled Downey to withstand his 20+ years in Chinese captivity?

Downey was a tough man. He was an accomplished wrestler and football player at Yale, and he trained to be a paramilitary CIA officer at Fort Benning in Georgia, where elite U.S. military forces train to this day. Downey managed to stay in good physical shape in prison by taking advantage of any opportunity to exercise. For his mental health, he tried to create routines to structure his day and, once he was able to, he tried to stay in touch by mail with friends and family back in the U.S.

He learned to study and appreciate things that people not in captivity might not fully appreciate, like the changing color of the sky at dusk that he viewed through a small window. He occasionally sought self-comfort by transporting himself back to the day in college when his Yale football team beat Harvard in the snow in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Perhaps above all else, he seemed to think of others first. He never wanted his family and friends back home to worry that he was suffering, even when things seemed rather hopeless during his original life sentence.

What books have you read lately that you would recommend, and why?

I just finished reading Kevin Rudd’s The Avoidable War, a learned and entertaining analysis of contemporary U.S.-China strategic competition. Rudd was Prime Minister and Foreign Minister of Australia, but before entering politics he trained as a China scholar of the first order. I think of him as the highest-ranking China scholar in the history of international relations. It was enriching to read such a smart analysis of U.S.-China bilateral relations, complete with sensible prescriptions, by someone who is not from either country.

Earlier this summer, I traveled to Norway to present a paper at the Nobel Institute. Upon my return and, on a friend’s recommendation, I read The Headhunters, a thriller by the Norwegian writer Jo Nesbo, which allowed me to spend a few more days in Norway in my mind. I am generally a reader of nonfiction, so I very much enjoyed this excursion.

What is next on your reading list?

I just received a book that looks great—An Unwritten Future by Jonathan Kirshner. The book revisits Thucydides, among other thinkers, to show how their work has been distorted by contemporary realist political scientists who promote an overly deterministic and, often, overly pessimistic approach to international politics. Kirshner wants to return to what he calls classical realism, an analytic approach that provides more room for domestic political influences, and the agency and psychology of individual leaders in determining policy outcomes.

What do you read when you're working on a book? And what kind of reading do you avoid while writing?

I devour everything I can find on the topic at hand, and I also try to stay up to speed on current events and debates in media outlets and policy journals. I tend to fall behind on scholarly journals and books in refereed presses that are unrelated to my book.

What are you teaching this fall?

I am teaching China’s Foreign Relations to both undergraduates and graduate students.

You're hosting a dinner party. Which three academics, dead or alive, would you invite, and why?

Perhaps I should choose more prominent people, but I would want to invite people I considered mentors and friends who have passed away, whom I miss, and from whose views on current events in U.S.-China relations, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and U.S-China-Russia triangular relations I would benefit greatly. I would also be interested in their impressions of Lost in the Cold War. One is Nancy Bernkopf Tucker, the late diplomatic historian of U.S.-China relations after whom the book series I edit for Columbia University Press was named. Nancy was a Georgetown University professor and had significant experience in the U.S. intelligence community.

A second guest would be Lucian Pye, my colleague and friend from MIT, where I taught for five years. Lucian was a giant in the field of comparative politics and Asian studies, who served in the U.S. Marine Corps in Northeast China just after the Japanese surrender in World War II, the same areas in which Jack Downey was carrying out operations targeting the Chinese Communists. Lucian believed in engagement, even with sworn enemies. He helped found the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations in the 1960s, when relations between the two countries were even worse than they are today.

Finally, I would invite Columbia’s own Robert Jervis, who passed away in December of 2021. A leading expert on international relations and political psychology and a long-time consultant to the U.S. intelligence community, Bob was one of my mentors when I was in grad school at Columbia, a colleague at SIPA after I arrived to teach here in 2018, and a good friend. I wrote an article in his honor with SIPA Dean Keren Yarhi-Milo in early 2022 in Foreign Affairs. I think of Bob regularly when I read the news, and I dedicated Lost in the Cold War to him. I wish that he could have read it.