How Spies and Codebreakers Won the Middle East in World War II

Historian and journalist Gershom Gorenberg uncovers how secret intelligence helped win the war for the Allies in the Middle East.

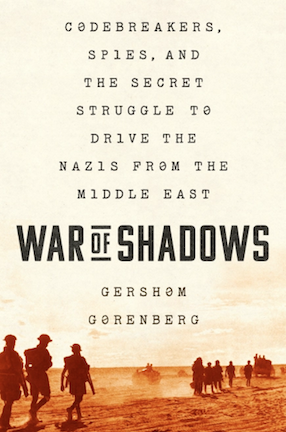

Accounts of military prowess and strategy in the Middle East during World War II are well documented, but tanks and rifles were not the only weapons used in those battles. In his historical book that reads like a spy novel, “War of Shadows: Codebreakers, Spies, and the Secret Struggle to Drive the Nazis From the Middle East,” Gershom Gorenberg, an adjunct lecturer at the Columbia School of Journalism, reveals how much the work of spies, British codebreakers, and pure chance changed the course of the war in that region.

Columbia News caught up with Gorenberg to find out what inspired him to write this book now, how he pieced the narrative together, and what codebreakers and spies he’d invite to an imaginary dinner party.

Q: In your introduction notes to “War of Shadows” you write that a conversation with your friend, Daniel Avitzour in Jerusalem moved you to write the book. Describe how this moment inspired you.

A: Daniel told me his father, a Palestinian Jew, had served as a British officer during World War II. The British army wanted to evacuate his mother—like other officers' wives—from Palestine because it was at risk of falling to the enemy. His story brought home how immediate the danger of Axis conquest of the Middle East had been, and how different the outcome of the war could have been. As I quickly learned, the SS had already appointed an Einsatzkommando to carry out genocide in Egypt and Palestine.

Then I came across garbled accounts of the espionage affair that spurred German general, Erwin Rommel, to invade Egypt—and that led to his defeat at El Alamein. I was obsessed with getting to the truth.

Q: Could you describe your process of gathering the documents, letters, and interviews that helped you to vividly recreate the scenes in "War of Shadows"?

A: I looked for official papers that would show the espionage trail and for personal material that would allow me to understand and portray the men and women involved. At the British National Archives I searched through thousands of documents, especially long-classified papers of Government Communications Headquarters, Britain's signal intelligence and codebreaking agency. I found more material in several American archives. My wonderful research assistant, Sam Miner, pored over captured German papers at the U.S. National Archives. A trove of key U.S. cables was missing from official collections; it turned up in the attic of a granddaughter of a colonel who served in Cairo. Colleagues shared Italian documents. Piecing them together, I could follow how the Axis pilfered Allied secrets, when and how the British found out, how America responded, and how all this changed battlefield decisions.

The personal papers were just as exciting: diaries of the famous and the forgotten, the unpublished memoirs of an MI5 colonel and of a woman who served as a British cipher officer in Egypt, the palm-sized logbook of a destroyer's navigator, and travel notes of Laszlo Almasy—the real Hungarian explorer, not the fictional one in The English Patient.

Q: How did the conflict in the Middle East during World War II shape the region today?

A: To start, the region would have changed in ways we can't chart or imagine had the Axis conquered the Middle East in 1942. So the combination of military decisions and codebreaking genius that produced British victory at El Alamein set the stage for everything since.

Beyond that, the war forced everyone to make fraught political choices. The British ambassador to Egypt instigated a coup in 1942 to install a pro-Allied prime minister. The coup delegitimized the old political order and set the stage for the 1952 Free Officers' revolution, from which Gamel Abdel Nasser and Anwar al-Sadat emerged as Egypt's leaders. During the war, the Egyptian military stayed on the sidelines, while up to 30,000 Jews in Palestine enlisted in the British military. The gap in experience played a role in the Israeli victory in the 1948 war. These aftershocks of World War II created the Middle East we know.

Q: Now that you’ve finished writing your book, hopefully you have some time to read for pleasure. What books are on your reading list?

A: I teach a course on writing history for journalists, and I'm always looking for good models. So I expect to be reading Reaganland, by Rick Perlstein and One Mighty and Irresistible Tide: The Epic Struggle Over American Immigration, 1924-1965, by Jia Lynn Yang. One of my favorite writers on Israeli history is Tom Segev, who is superb at plunging into a historical figure's character, so I need to read his biography of David Ben-Gurion, A State at Any Cost. And I've been waiting to get to Stephen Greenblatt's Tyrant: Shakespeare on Politics to better understand how Shakespeare wrote politics.

A: You are hosting a small dinner party. Assuming everyone is fully vaccinated, which three scholars, authors, World War II codebreakers, or artists, dead or alive, would you invite and why?

Q: That's easy: Marian Rejewski, the Polish mathematician who cracked Germany's supposedly unbreakable Enigma cipher in 1933; Genevieve Grotjan, the American mathematician who figured out in 1940 how Purple, Japan's diplomatic cipher, worked; and Margaret Storey, the British intelligence analyst who sorted through deciphered Enigma messages in 1942 to identify Germany's prize source in the Middle East. They were young and working under incredible pressure, and could talk to very few people about what they'd done, so I'd love to listen to them talk with each other. Perhaps I'd learn how much of their breakthroughs was conscious analysis and how much was leaps of brilliant intuition—sparks leaping between two charged points in the clouds of half-consciousness.

Check out Books to learn more about publications by Columbia professors.