What Is Critical Race Theory, and Why Is Everyone Talking About It?

Columbia Law School professors explain this method of research for legal scholars and how it’s being misunderstood.

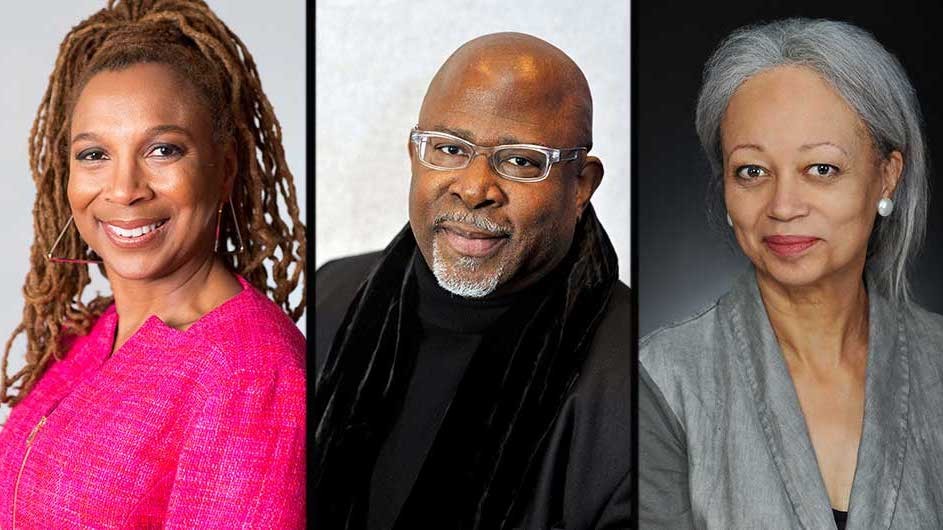

Critical race theory is making national news headlines, and three pioneers of this academic discipline are Columbia Law professors Kimberlé Crenshaw, Kendall Thomas, and Patricia Williams.

Republican lawmakers in more than 20 states have introduced or passed legislation that would directly target the principles underlying critical race theory by banning schools from teaching about structural racism. These efforts to demonize critical race theory are gaining traction more than a year into a national reckoning with racism, following the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and the ensuing protests.

Speaking at a conference held by the Faith and Freedom Coalition on June 18, former Vice President Mike Pence said that “critical race theory is racism.” Senator Ted Cruz, at the same gathering, compared the theory to the Ku Klux Klan saying the curriculum is “every bit as racist” as the white supremacist hate group. “Critical race theory,” the senator said, “says every white person is a racist.”

These campaigns are not just based on ignorance of how critical race theory developed and is now applied, but also represent an attempt to stoke a reactionary resistance, rather than a broader understanding.

Urgent and Necessary Work

“Critical race theory and the essential scholarship it has advanced may challenge many long-held views, but that is what makes this work so urgent and necessary,” said Columbia President Lee C. Bollinger (LAW’71). “I could not be more proud that it is taking place at Columbia. This is, after all, what makes universities such vital institutions in society.”

“In the finest tradition of Columbia Law School, our brilliant faculty were among the foundational thinkers and continue to lead the dialogue on this vital issue,” said Gillian Lester, Dean and Lucy G. Moses Professor of Law. “Their scholarship, teaching, and advocacy have illuminated the pervasive effects of structural racism in our society and in the law. That they have persisted in the face of hostility and outright falsehoods is testament to their vision and determination."

Critical race theory was a movement that initially started at Harvard under Professor Derrick Bell in the 1980s. It evolved in reaction to critical legal studies, which came about in the 70s and dissected the idea that law was just and neutral. Over time, the movement grew among legal scholars, mostly of color, at law schools across the country, including at UCLA, where Crenshaw lectured on critical race theory, civil rights, and constitutional law, and later at Columbia, where she was appointed a full professor in 1995, alongside Williams, a former student, research assistant, and lifelong mentee of Bell’s, and who is now professor of law emerita.

Critical Race Theory in the News

Although the scholarship differs in emphasis and discipline, it is united by an interest in understanding and rectifying the ways in which a regime of white supremacy and its subordination of people of color in America has had an impact on the relationship between social structure and professed ideals such as “the rule of law” and “equal protection.”

Put simply, according to Crenshaw, who coined the term intersectionality, which refers to how different forms of discrimination (such as sexism and racism) can overlap and compound each other, critical race theory is a way to talk openly about how America’s history has had an effect on our society and institutions today.

“We need to pay attention to what has happened in this country and how what has happened is continuing to create differential outcomes, so that we can become the democratic republic we say we are,” Crenshaw explained. “We believe in the promises of equality, and we know we can get there if we confront and talk honestly about inequality.”

Forcing Legal Scholars to Ask Questions

Critical race theory essentially forces legal scholars to ask questions, she continued. For instance, why does possession of less expensive drugs carry higher jail sentences than more expensive drugs? Could this have anything to do with the fact that more people of color are in prison?

“It is a way of looking at law’s role platforming, facilitating, producing, and even insulating racial inequality in our country, ranging from health to wealth to segregation to policing,” said Crenshaw, who is also the co-founder and executive director of the African American Policy Forum.

For those, like Senator Cruz, who say that critical race theory assigns blame to white people, that’s wrong, said Thomas, who is the Nash Professor of Law and a member of the faculty at Columbia Law School since 1984. He teaches a critical race theory workshop, among other courses, and directs the Center for the Study of Law and Culture.

"Critical race theory views race law and policy as tools of power," Thomas said. "Its focus on the politics of race has helped break the stranglehold of 'racial moralism' by challenging the egocentric belief that racism is always only about personal fault, private prejudice, and invidious individual intent. Critical race theory tells a story about institutionalized racial disadvantage and systemic racial inequality. It highlights the structural harms of the ‘colorblind racism’ we see at work in laws that don’t mention race per se."

Want to Dive Deeper?

For parents or educators who, according to G.O.P. lawmakers, say that white children are being made to feel guilty and being taught that white people are oppressors, Thomas replied, that this “is not, by any stretch of the imagination, an idea or tenet behind critical race theory. To the contrary, critical race theory recognizes that racial inequity and exclusion hurt all Americans, whatever our race or color. In the famous Brown decision, the Supreme Court emphasized that education is the 'very foundation of good citizenship.' The families and teachers who oppose the attacks on critical race theory know that we can't censor classroom discussions about the meaning of race if we want to prepare young Americans for the responsibilities of democratic citizenship in our increasingly diverse multicultural society."

Furthermore, said Thomas, “the people behind this legislation are trying to prevent the emergence of a broad movement for multiracial democracy to address the interconnected economic, social, and political inequality that is devastating poor and working-class communities of all races in this country.”

This Is About Racial Justice

For Crenshaw, the legislative efforts are scapegoating. “The idea that anti-racism is racism against white people has got to be the oldest talking point in their playbook. There is not a thing happening today that we have not seen before, including the ascendance of racial demagoguery on the anti-democratic, authoritarian, and nationalist impulses of a population mobilized through the discourse of aggrievement,” she said.

“We saw this in the backlash against emancipation. We saw it in the successful effort to disenfranchise African Americans and purge them entirely from public life, and we saw aggressive and even violent actions justified as self-defense," she said.

What is going on today is about racial justice. “This hysteria is just that. It has nothing to do with a legal theory that has been around for decades, and that you may never have heard of until now,” Crenshaw said. “If you marched last year in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, if you have a Black Lives Matter sign on your lawn or a bumper sticker on your car, if you had diversity training at your job and now you understand how you can do better, then you support racial justice.”