Zoë Crossland Mines the Connections Between Anthropology and Archaeology

Human remains are at the heart of Zoë Crossland’s work. In one of the most popular classes that she teaches, Corpse Life, students learn about the history of death and the treatment of remains.

She is also working on a new book, The Speaking Corpse, which explores the development of forensic approaches to examining the dead. While this research focuses on the body, Crossland, a professor in the anthropology department and director of Columbia’s interdepartmental Center for Archaeology, notes that she’s “quite happy to work with grotty bits of broken earthenware pottery or soil sediments.” These things, she said, “aren’t glamorous or exciting, but they hold a great deal of valuable information about how people lived in the past.”

As an anthropologist and archaeologist, Crossland readily admits that the distinction between the two disciplines can be confusing. In her native England, universities tend to have more purely archaeological departments than in the U.S., where the two fields tend to overlap.

“I think what makes me more of an anthropologist than an archaeologist is my interest in people as opposed to things. The things are a way to get at the history of people,” she said. Crossland, who arrived at Columbia in 2006, notes that there are “archaeologists all over the University—in history, East Asian languages and cultures, art history.” Trained at Cambridge University, she later attended the University of Michigan, earning her M.A. and Ph.D. degrees in archaeological anthropology.

Before starting college, she spent a year volunteering on digs in Peru and Argentina, where she visited an excavation in Buenos Aires and saw exhumed remains of people who disappeared during the country’s Dirty War in the 1970s.

“Seeing graves like that makes a forceful impact,” she said. The experience led to her interest in forensic archaeology and what she calls “evidentiary practices” around human remains.

While at the University of Michigan, Crossland traveled to Madagascar for the first time to help conduct fieldwork on early tombs, settlement sites and fortifications in the highlands, which resulted in her specialization in the historical archaeology of that island nation.

The thread running through her projects is evidence.

“As anthropologists, we write these narratives about the past, but it doesn’t exist,” she said. “Our stories are based on material traces that we live among and use to reconstruct what’s been and gone. How do we get from the objects to that knowledge? That’s the question that motivates me and that I try to impart to my students.”

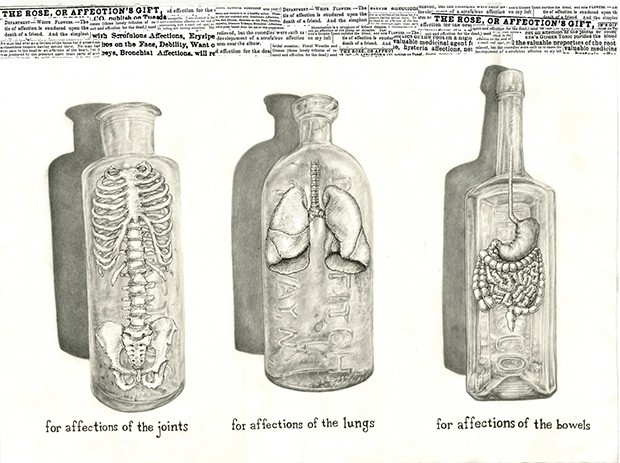

Crossland investigates that question in a new class, Science and Art in Archaeological Illustration (co-taught with painter and visual arts alumna Tracy Molis), which looks at how art plays both a conceptual and a practical role in archaeology. Students explore different illustrative techniques by mixing colors and finding ways to depict ancient ceramics or stone, landscapes and even human and animal remains.

“I want the students to think about that question of evidence. When you represent something in an illustration, what kind of argument are you constructing, what choices are you making in terms of what’s portrayed and what’s left out?” explained Crossland.

This fall she is teaching another new class, The Emerging City: Environmental Histories of New York, with Nan Rothschild, professor emeritus of anthropology at Barnard and an adjunct anthropology professor at Columbia, along with Jonathan Nichols and Dorothy Peteet, environmental researchers at the University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. To answer current questions about human impact on the environment, the interdisciplinary course tracks the city’s environmental history. Students are going on a field trip to a salt marsh in Staten Island to take sediment cores, which they will then analyze in the lab. They are learning how to use critical thinking to assess the ways in which evidence is interpreted and brought into larger scientific and policy debates.

“Again, it’s thinking about how evidence—in this case, environmental evidence such as sediment cores—is rolled into narratives about climate change, pollution, toxicity that shift over time. You need to understand the limits of this evidence,” said Crossland.

This summer, Crossland returned to Madagascar with two doctoral students in anthropology to continue her fieldwork in the highlands. The focus on this trip was rice and how it can be used as a lens through which to examine not only the history of Madagascar, but also trade throughout the Indian Ocean.

“Columbia students are so sparky,” said Crossland. “They challenge me and disagree with me, which is what you want, not just passive recipients who listen and don’t react.”