Columbia Tests Wastewater in Residence Halls for Coronavirus

The University will routinely monitor sewage leaving student dormitories to head off outbreaks of COVID-19.

Columbia is ramping up a program to test wastewater in residence halls to identify signs of the novel coronavirus before a widespread outbreak of COVID-19 can occur.

Wastewater sampling began last week at several dormitories with the goal of detecting traces of genetic material from SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Many people infected with the virus exhibit mild or no symptoms, and analysis of bodily fluids in wastewater can serve as an early indicator of potential hotspots for infection.

“Wastewater analysis is a simple, yet sophisticated, way to shed light on infectious disease transmission in a community,” said Wafaa El-Sadr, who oversees the Public Health Committee for the University COVID-19 Task Force. “It can provide an early warning signal for the presence of COVID-19 cases, leading to the mobilization of a rapid response.”

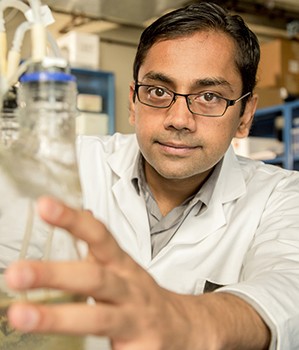

The pilot program, spearheaded by El-Sadr, professor at the Mailman School of Public Health and ICAP global director, is a collaborative effort involving University Facilities and Operations, Columbia Health, and a research team at Columbia School of Engineering, led by Kartik Chandran, a global expert in sustainable wastewater management and sanitation.

Chandran, a professor of environmental engineering, is leading several wastewater SARS-CoV-2 surveillance and viral genomics studies worldwide, including programs in the greater New York City area, New England, and the Southeastern United States.

Chandran explained that people infected with SARS-CoV-2 shed the virus in their feces and other bodily fluids even before they show symptoms of COVID-19. (To date, there has been no definitive evidence that the COVID-19 virus can be transmitted through non-respiratory body fluids.)

“Our studies and others comparing wastewater data and hospital records have found that SARS-CoV-2 prevalence in wastewater can, in some cases, precede clinical evidence of infection,” Chandran said. “That buys decision makers valuable time to assess and take actions, such as additional testing, quarantine, or following up with close contacts.”

At Columbia, where nearly 1,000 undergraduates currently live on campus, scientists have collected waste samples from four dormitories. Testing involves sampling wastewater from pipes in the building, concentrating the genetic material in the sample, and then analyzing the sewage to detect SARS-CoV-2 and other viral genomic material.

Tracking a Pandemic

All virus analysis is done in-house by Chandran’s group at his lab in the Seeley W. Mudd engineering building consistent with CDC guidelines, and results from the initial testing showed no traces of SARS-CoV-2. Further sampling and testing are ongoing. Chandran’s lab has the capacity to process up to 100 samples per day with results within 24 to 48 hours.

Preliminary plans call for two to three weekly sewage samples to be collected from each building with more residence halls added to the surveillance program throughout the semester.

Should testing reveal a spike in coronavirus being shed through waste in a residence hall, follow-up protocols are in place.

Melanie Bernitz, associate vice president and medical director of Columbia Health, said that once officials validate the data, students in the affected building would be notified immediately of the wastewater results, quarantine would be recommended, and individual SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic testing would occur for building occupants to determine the potential source of the spike. The students are tested for COVID-19 weekly.

Bernitz finds wastewater testing an intriguing strategy, with potential for expansion. “It’s important to look at alternate approaches to keeping everyone on campus safe, and the technique holds promise for predicting COVID hotspots quickly,” she said.

But she wants to make sure people understand that wastewater testing is not meant to supplant existing COVID-19 surveillance systems and prevention measures.

“This is not a magic bullet. It’s not about replacing diagnostic testing and contact tracing,” Bernitz said. “What it does is offer another tool for tracking the spread of COVID-19 that can feed into the University’s overall prevention and detection strategy.”

“We are fortunate to have several tools in our COVID-19 prevention toolbox at this point,” El-Sadr said. “We know what it takes to stop the spread of this virus, and the Columbia COVID-19 strategy brings this knowledge to action for the benefit of our community.”