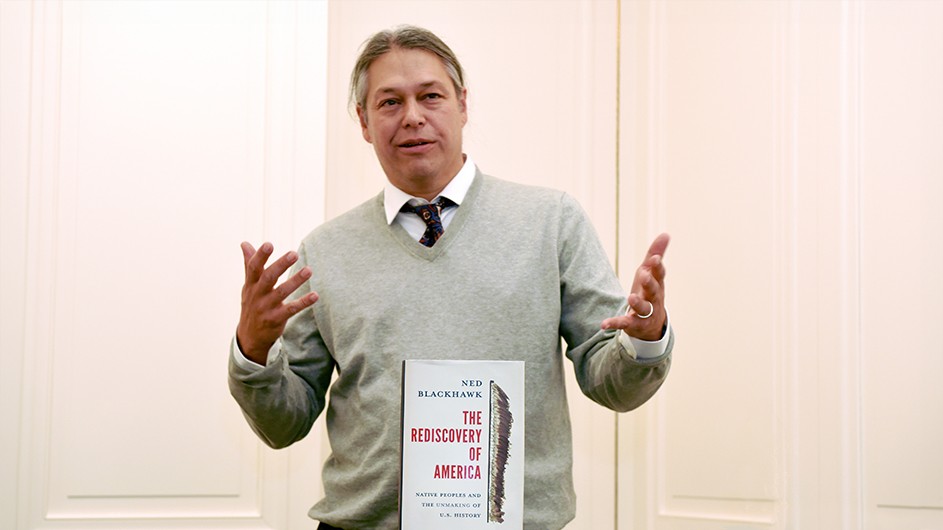

Ned Blackhawk, Winner of the 2023 National Book Award for Nonfiction, Speaks at Columbia

His book, The Rediscovery of America, offers an overview of U.S. history with Indigenous figures at the center.

Ned Blackhawk spoke about Native American scholarship and archives on November 17 at an event sponsored by Columbia’s Lehman Center for American History. Two days earlier, he had won the National Book Award for Nonfiction for The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of U.S. History.

“Was it earlier this week, or earlier this morning?” joked Blackhawk, the Howard R. Lamar Professor of History and American Studies at Yale University. He remained visibly moved by the accolade. “That happened less than 48 hours ago, and I still can't process it. It’s been a pretty eventful week.”

A member of the Te-Moak Tribe of Western Shoshone Indians of Nevada, Blackhawk said that he hopes excitement around the prize will encourage more people to engage with Indigenous stories. “I know it’s a lot easier to just do other things,” he said. “Native American history is not familiar; it’s a little discomforting. But it’s a beautiful field, if you come to see it, because the insights can be quite generative, and often challenging. They make us think differently about things like citizenship, freedom, liberty.”

A New Overview of U.S. History

The Rediscovery of America offers an overview of U.S. history, from first contact to the 21st century, with Indigenous figures at the center. Among those he examines are Laura Cornelius Kellogg, an Oneida woman and one-time Barnard College student, who helped found the Society of American Indians, and Ada Deer, a graduate of Columbia’s School of Social Work, who served as assistant secretary of the Interior for Indian Affairs.

The Lehman Center for American History, which is a collaboration between the Rare Book and Manuscript Library and the Department of History, invited Blackhawk as part of an ongoing conversation on Native American history. Previous events in the series have included a book talk by Columbia History Professor Michael Witgen, and a panel discussion on Black and Native Citizenship: The Making of American Identity Past and Present.

Despite years of study in Indigenous histories, there is an acute need for further research, particularly in the New York area. “There is an intense interest,” said Blackhawk. “A lot of people are asking me what I know about the Lenape communities that were in these spaces. But given the lack of sources, or scholarly studies, it’s hard to make sense of it all. You can’t just Google it.”

Going Back to the Archival Sources

To pursue this information, scholars are looking again at archival sources, including documents held by the RBML. From early audio recordings and printed books, to ethnographic records collected by Columbia anthropologists, the RBML serves as a custodian for a wide variety of Native American materials.

These collections were acquired by Columbia’s libraries decades—and sometimes more than a century—ago. They were often improperly identified and misinterpreted, and in the years since, have frequently served to reinforce colonial perspectives. Recent initiatives have begun correcting some of these historical legacies, and library staff now emphasize collaboration with creator communities. “Archivists have an ethical duty of stewardship to collections that reflect Indigenous people,” said Kevin Schlottmann, RBML head of archives processing. “This means making sure the existence of these records is known to tribes, that sustained community consultation takes place, that requests for restrictions on traditional or sacred knowledge are taken seriously, and that, when appropriate and desired, original records or digital reproductions are repatriated.”

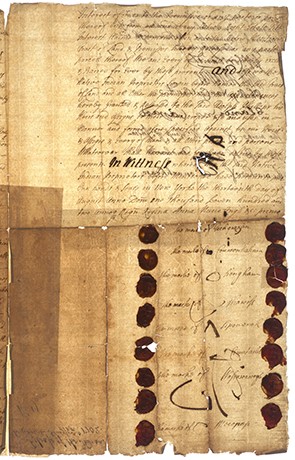

A 1702 land deed in the RBML’s Philipse-Gouverneur family collection is the type of document that can provide insights into New York’s Indigenous history. Granting roughly 250 square miles in the Hudson Valley to Adolph Philipse, a prominent landowner and enslaver (several of whose descendants would go on to attend King’s College, the original name of Columbia), the deed contains the signatures of a dozen Native leaders from the local Wappinger tribe.

This document shows how New York’s Indigenous people navigated questions of sovereignty and power. “Native signatures on treaties and other contracts were typically inscribed by those who understood themselves as historical, economic, and political agents,” said Ryan Carr, a Columbia lecturer in English and comparative literature and American studies, whose new book, Samson Occom: Radical Hospitality in the Native Northeast, profiles the first Native person to be ordained a minister in the New England colonies.

An Object Touched by Their Kin

Beyond any historical evidence the 1702 land deed may contain, it also has cultural value. “The Wappinger signatories to this document were ancestors of people living today,” Carr said, “people who might see this not (or not only) as a colonial document, but rather as an object touched by their kin.”

Carr added that libraries should make efforts to contact the descendants of those who signed such records in order to learn their perspectives. Blackhawk also noted the need for Indigenous expertise in archival collections and libraries.

“Museums are often traumatic places for Native Americans,” Blackhawk said, but archival collections have a somewhat different meaning. “Because so many Native peoples have sought in archives the evidentiary bases for their claims against outside interests, archives have yielded many of the achievements that are at the heart of the modern American Indian sovereignty movement.”

Thai Jones is the RBML Lehman Curator for American History and a lecturer in the History Department.