New Exhibit and Book Detail Columbia's Italian Connection

Lorenzo Da Ponte took a circuitous route to becoming Columbia’s first professor of Italian. Born in 1749 into a Jewish family near Venice, he converted to Catholicism and was briefly a priest until it was discovered he had fathered two children with his mistress. Banished from Venice, he turned up in Vienna at the court of the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II, where he met Mozart, and became the librettist for three of the composer’s operas.

Acclaim followed, but not wealth. Bankrupt after Mozart’s death, Da Ponte decamped to London with a new woman.

Image Carousel with 10 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

Slide 1: On the eve of the Casa Italiana’s inauguration in October 1927, a banquet welcomed Senator Guglielmo Marconi, the Nobel Prize–winning chemist who was representing Italy’s Fascist government. At the table of honor with Senator Marconi (and leaders of the Fascist League of North America) were Columbia's President Butler; Judge John Freschi, who had led the fundraising campaign; the Paterno family that developed the Casa and underwrote the cost of building it (Michael, Charles, and Joseph Paterno); the head of the Italian Chamber of Commerce (Attilio Giannini); N.Y.’s governor, mayor, and cardinal; both of N.Y.’s senators; Rabbi Stephen Wise; and banker Otto Kahn.

-

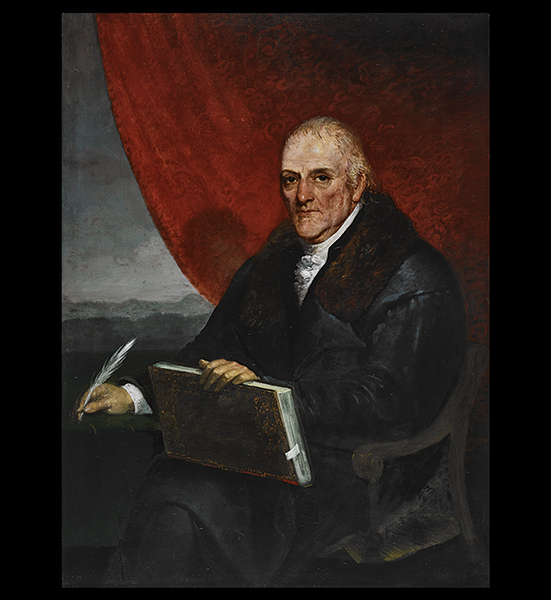

Slide 2: Portrait of Lorenzo Da Ponte (1749–1838), early 19th century, oil on canvas. Artist unknown. Image Courtesy of Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library

-

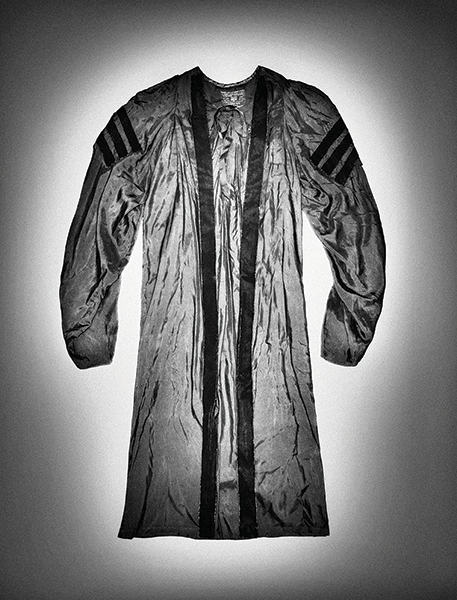

Slide 3: Da Ponte’s formal silk professorial gown. Photo by Kevin Sweeney, 2017

-

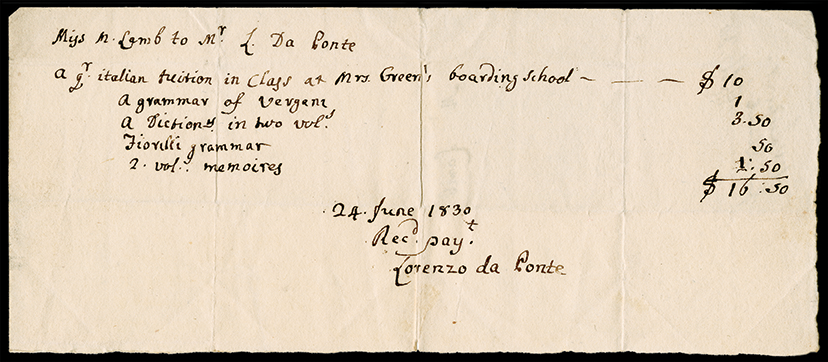

Slide 4: While a professor at Columbia, Da Ponte (like many of his peers) was not salaried, but simply permitted “a reasonable compensation” directly from his students. He handled his own billing and receipts. Lorenzo Da Ponte Receipt of Tuition Payment, June 24, 1830, RBML, General Manuscripts (1789–2013).

-

Slide 5: Children of immigrants to Harlem’s Little Italy, as well as first-generation students and scholarship holders, gathered to form Italian clubs at Barnard (above) and at Columbia; these students campaigned to have an Italian center on campus. Barnard Mortarboard yearbook 1937 (Il Circolo Italiano, p. 95). Image Courtesy of Barnard Archives

-

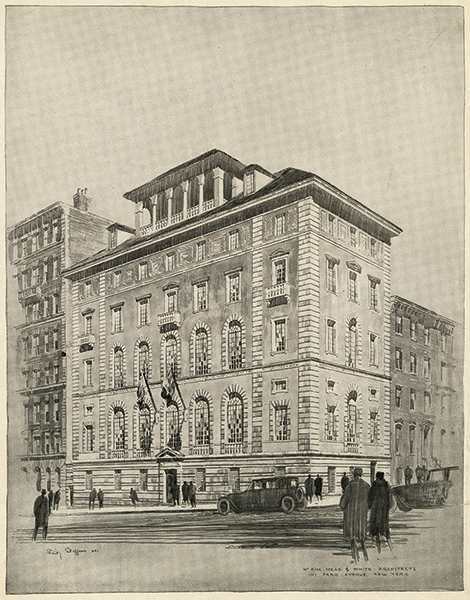

Slide 6: Modeled on a Roman palazzo of the Renaissance, the Casa Italiana building was, like the imposing Low Library, completely clad in limestone (amid the more common brick façades of the Columbia campus). This architect's sketch stresses the lively variety of stonework and textures. Image Courtesy of New York Historical Society

-

Slide 7: President Butler helped to lay the cornerstone of the Casa in August 1926, using a mallet and the ceremonial silver trowel that was brought out for the cornerstones of all campus buildings. Inside this cornerstone was a zinc box holding Latin inscriptions as well as publications charting the building’s development. Image Courtesy of Historical Photograph Collection, Columbia University Archives

-

Slide 8: Dr. Charles Paterno, of the immigrant family that built the Casa, bought thousands of books for the library. Paterno and others continued giving so rapidly that, by 1930, it was clear that the collection would outgrow the Casa and be transferred. Indeed, the Paterno Collection is now accessible in the campus’s Butler Library. Image Courtesy of Historical Photograph Collection, Columbia University Archives

-

Slide 9: This photo from the 1920s shows the building flanked by row-houses on 117th Street and other residences on Amsterdam Avenue. Image Courtesy of Historical Photograph Collection, Columbia University Archives

-

Slide 10: The auditorium, with its coffered, gilded ceiling, had windows only on Amsterdam Avenue, at one point; it did not open eastward. Image Courtesy of Historical Photograph Collection, Columbia University Archives

On the eve of the Casa Italiana’s inauguration in October 1927, a banquet welcomed Senator Guglielmo Marconi, the Nobel Prize–winning chemist who was representing Italy’s Fascist government. At the table of honor with Senator Marconi (and leaders of the Fascist League of North America) were Columbia's President Butler; Judge John Freschi, who had led the fundraising campaign; the Paterno family that developed the Casa and underwrote the cost of building it (Michael, Charles, and Joseph Paterno); the head of the Italian Chamber of Commerce (Attilio Giannini); N.Y.’s governor, mayor, and cardinal; both of N.Y.’s senators; Rabbi Stephen Wise; and banker Otto Kahn.

Portrait of Lorenzo Da Ponte (1749–1838), early 19th century, oil on canvas. Artist unknown. Image Courtesy of Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library

Da Ponte’s formal silk professorial gown. Photo by Kevin Sweeney, 2017

While a professor at Columbia, Da Ponte (like many of his peers) was not salaried, but simply permitted “a reasonable compensation” directly from his students. He handled his own billing and receipts. Lorenzo Da Ponte Receipt of Tuition Payment, June 24, 1830, RBML, General Manuscripts (1789–2013).

Children of immigrants to Harlem’s Little Italy, as well as first-generation students and scholarship holders, gathered to form Italian clubs at Barnard (above) and at Columbia; these students campaigned to have an Italian center on campus. Barnard Mortarboard yearbook 1937 (Il Circolo Italiano, p. 95). Image Courtesy of Barnard Archives

Modeled on a Roman palazzo of the Renaissance, the Casa Italiana building was, like the imposing Low Library, completely clad in limestone (amid the more common brick façades of the Columbia campus). This architect's sketch stresses the lively variety of stonework and textures. Image Courtesy of New York Historical Society

President Butler helped to lay the cornerstone of the Casa in August 1926, using a mallet and the ceremonial silver trowel that was brought out for the cornerstones of all campus buildings. Inside this cornerstone was a zinc box holding Latin inscriptions as well as publications charting the building’s development. Image Courtesy of Historical Photograph Collection, Columbia University Archives

Dr. Charles Paterno, of the immigrant family that built the Casa, bought thousands of books for the library. Paterno and others continued giving so rapidly that, by 1930, it was clear that the collection would outgrow the Casa and be transferred. Indeed, the Paterno Collection is now accessible in the campus’s Butler Library. Image Courtesy of Historical Photograph Collection, Columbia University Archives

This photo from the 1920s shows the building flanked by row-houses on 117th Street and other residences on Amsterdam Avenue. Image Courtesy of Historical Photograph Collection, Columbia University Archives

The auditorium, with its coffered, gilded ceiling, had windows only on Amsterdam Avenue, at one point; it did not open eastward. Image Courtesy of Historical Photograph Collection, Columbia University Archives

A dozen years later, he boarded a ship to America called, fittingly, The Columbia. He started a grocery store and a distillery, which both failed.

Then he met the poet Clement Clarke Moore (CC 1798), best known for writing “Twas The Night Before Christmas,” whose father and uncle had been presidents of Columbia College. In 1825, at the age of 76, Da Ponte was named the College’s first professor of Italian, where he remained until he died at age 89.

“America was not wholly ready for him,” said David Freedberg, director of the Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America, a center for wide-ranging scholarship at Columbia. Da Ponte was accustomed to high culture in Europe, while America had not yet developed cultural institutions to rival the continent.

Da Ponte, whose real name was Emanuele Conegliano, helped create Italian studies not just at the University but in this country, promoting the riches of the culture and bringing its opera to these shores. An Italian troupe that was among the best from Europe came to perform a selection of Il Barbiere di Siviglia, Otello, and other operas. In 1826, they performed Mozart’s Don Giovanni using Da Ponte’s libretto.

His story is chronicled in a new book called From Da Ponte to the Casa Italiana: A Brief History of Italian Studies at Columbia University, by Barbara Faedda, associate director of the Italian Academy and adjunct assistant professor in the Department of Italian. It marks the 90th anniversary of an institution that has played a leading role in fostering U.S.-Italian relations.

On the ground floor of its 1927 neo-Renaissance building on Amsterdam Avenue, which you might mistake for a palazzo in Florence or Rome, Faedda and her colleagues recently mounted an exhibit about the history of Casa Italiana, which became the Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America in the early 1990’s. Casa Italiana was originally intended to be a library, but Columbia president Nicholas Murray Butler had greater ambitions. Teodolinda Barolini, Da Ponte professor of Italian and former long-time chair of the Italian department, said that Columbia’s Italian department, located across Amsterdam Avenue in Hamilton Hall, looks upon the Italian Academy as “our glamorous sister.”

“Casa Italiana became an active center between the United States and Italy,” said Faedda, whose book extensively documents the Fascist sympathies of the controversial Giuseppe Prezzolini, who became the Casa’s director in 1930, and even Butler himself. “I hope to get back to Italy, in which I should wish, of course, to pay my respects to him [Mussolini] once more,” wrote Butler to Prezzolini in 1933. As Faedda notes, Il Duce himself had promised to provide furniture for the Casa from Italian palaces, but it never came to pass.

Faedda also describes how Casa Italiana hosted a Jewish club in the 1930s, Marxist lectures, and protests against Nazi anti-Semitism. By 1942, when Columbia was part of the war effort, “the auditorium became a work room for cutting and sewing garments and making surgical dressings.” Even so, during World War II the name Casa Italiana over the front doorway was covered, given that Italy was a U.S. enemy.

At the opening reception for the exhibit about Da Ponte and Casa Italiana, Consul General of Italy Francesco Genuardi described the longstanding friendship between his country and the Italian Academy, saying, “We feel at home here.” He pointed out that Da Ponte was hired at Columbia decades before Italy was declared a unified nation-state in 1861. Faedda said, “The love, passion, and interest that New Yorkers have for Italy and its culture, art, and music makes the relationship between Italy and New York special.”