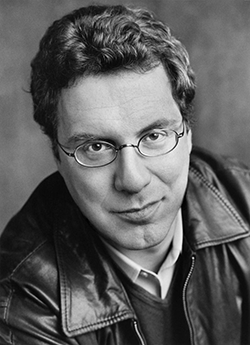

Professor Jeremy Dauber Gets Serious About Jewish Comedy

The conundrum facing Jeremy Dauber as he worked on his latest book is embodied in the title: Jewish Comedy: A Serious History. Dauber, the Atran Professor of Yiddish Language, Literature and Culture in the department of Germanic languages, was well aware that “analyzing comedy runs the risk of killing it.” Still, he forged ahead, chronicling the arc of Jewish humor “from the Bible to Twitter,” as he puts it.

Dauber has essentially been researching the subject of Jewish comedy since he came to Columbia in 2000. Two of the earliest classes he taught were on humor in Jewish literature and on the famed Yiddish author Sholem Aleichem, the subject of his 2013 book, The Worlds of Sholem Aleichem: The Remarkable Life and Afterlife of the Man Who Created Tevye. (Born in 1859, Aleichem is best known for his humorous short stories of shtetl life, which later inspired the Broadway musical Fiddler on the Roof.)

His latest book, which will be published Oct. 31, makes no claims about metaphysical, spiritual or theological meaning in Jewish comedy. “I thought there was an opportunity to take the scholarship and put it into a comprehensive, entertaining form for a mainstream audience,” he said. “It’s a way of telling the story of comedy over the Jews’ long history.” He is quick to add, “you want a joke book, buy a joke book.” What Dauber does provide are many examples of how Jewish comedy works and how a particular routine or story can powerfully express the anxieties and ambitions of mid-20th century American Jewish life.

Beware: some readers might find offensive, obscene or blasphemous material in Jewish Comedy. “Fat jokes,” he points out, are found in earliest recorded history even as such humor is increasingly seen as inappropriate. “You have been warned,” he writes in the introduction.

Humor can be traced back to the earliest Jewish texts, the Bible and the Talmud. “There’s vulgar and earthy humor in the Bible as well as satire,” he said, adding that for centuries traditional Jews viewed the Book of Esther as a great source of comedy. “It’s the first work to feature the joyful celebration and comic pleasure that comes with an anti-Semite’s downfall,” Dauber explained. “If there’s any truth to the phrase, ‘They tried to kill us, we survived, let’s eat,’ it comes from the story of Esther and the festive holiday of Purim, one of the highlights of the Jewish year.”

Early in his book, Dauber observes that Jews weren’t considered to be funny until fairly recently. “They had a kind of essential sadness about them because they missed the Christian boat of salvation,” he said. He cites the early-20th century British philosopher Albert North Whitehead, who remarked that Jews are “singularly humorless.”

While Dauber notes how essential humor is to modern Jewish identity, he suggests that this is a recent development. In a 2013 Pew Research Center study, “A Portrait of Jewish Americans: Overview,” 42 percent of respondents indicated that “having a good sense of humor” was part of “being Jewish in America today,” 14 percent more than selected “being part of a Jewish community” and 23 percent more than selected “observing Jewish law.”

Related: In A Predominantly Christian Country, Why Is Jewish Humor So Popular?, Forward, Oct 27, 2017

Dauber doesn’t believe that Jews are funnier or braver or smarter than any other particular group of people. So how did American Jews become so identified with comedy? For that, he says, thank anti-Semitism.

In the early and middle decades of the 20th century, most American Jews were prevented from joining many high status professional fields. As a result, they entered all sorts of occupations that were considered “low class,” especially popular entertainment. Jewish comedians flourished in vaudeville and the Borscht Belt resorts of upstate New York’s Catskill Mountains, in nightclubs and radio, then, ultimately, in television. “That was often one of the main ways in media that you saw Jews,” said Dauber.

“Today,” he continued, “the freedom of comedy brings us the broad range of Jewish humor.” He mentions Larry David, “one of the great expositors of Jewish-gentile comedy;” the stars of the Comedy Central show Broad City, “who are vulgar in the best possible ways”; the witty Megan Amram on Twitter; and Joshua Cohen, “a great American novelist, who has a mordant, sophisticated sense of humor.”

Earlier this year, Dauber stepped down as director of Columbia’s Institute for Israel and Jewish Studies, which he had run since 2008. He is now on sabbatical, working on two new books: a history of American comic books and graphic novels, and a history of Yiddish literature and culture.

As for his latest book, he says, “It will make a great bar mitzvah gift.”