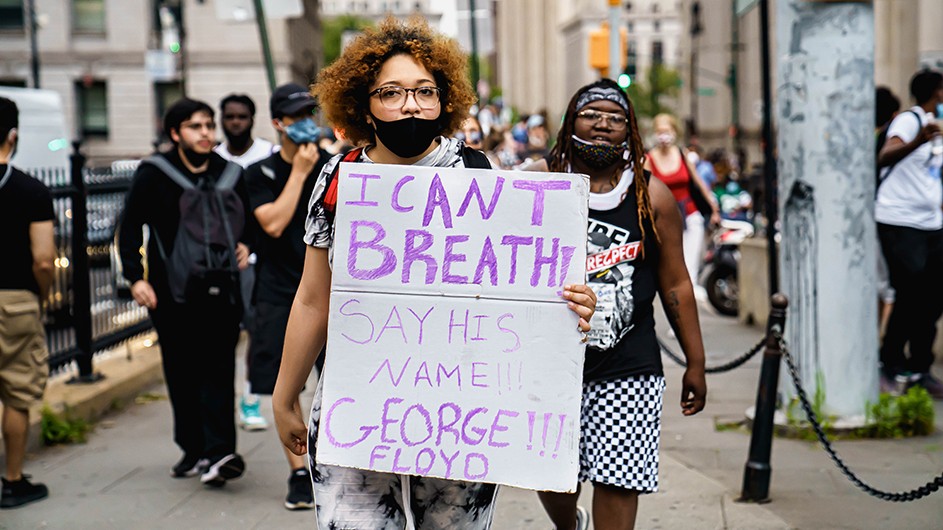

America Responds to the Death of George Floyd

“When we revolt it's not for a particular culture. We revolt simply because, for many reasons, we can no longer breathe," wrote political philosopher Frantz Fanon in The Wretched of the Earth, one of the seminal texts in Columbia's Core Curriculum.

Fanon's words are a poignant reminder following the death of George Floyd, when the pervasive problems of racial injustice and violent policing have once again come to the fore in the U.S., igniting protests across the nation and fierce debate on how to bring about lasting change.

Here, Columbia Professors Frank Guridy, Wilmot James and Charles V. Hamilton share their perspectives on anti-black violence, public anger and the nature of protest.

Historic Protests Necessitate Historic Action by American Political Leaders

By Frank Guridy

American democracy is being reinvigorated on the streets of Minneapolis. It is being refashioned by the crowds that converged on the Barclays Center in Brooklyn, by those who marched along 125th Street in Harlem and by those who provided shelter for teargassed protesters in Washington, D.C. And yes, democracy is being revitalized even in the shattering of storefront windows and the symbolic acts of defiance against corporate interests that have colonized cities and dispossessed the urban laboring majority since the 1990s. These powerful manifestations of solidarity have illustrated not only the absolute anger at yet another incident of police brutalization of black people, but also an explicit rejection of a government that has consistently put the interests of corporate elites ahead of those of the majority of Americans. The willful disregard has been made painfully clear by the allocation of financial relief during the COVID-19 pandemic.

What we are seeing is the emergence of a powerful protest movement that is building on decades of activism and consciousness-raising by exposing the unrelenting practice of police brutality, mass incarceration, income disparities, sexism, patriarchy and racism. These are long-standing issues that have been particularly pronounced since the financial crisis of 2008 and the flowering of the Black Lives Matter Movement that took shape after the murders of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown. Protesters are highlighting the systemic quality of oppression, not merely the actions of bad cops and individual racists. As a protester in Brooklyn succinctly put it: “I’m not here to fight someone, I’m here to fight a system.”

And yet the vast majority of elected officials and mainstream media outlets continue to propagate a willful misunderstanding of our current catastrophe. The Trump administration’s call to repress the protesters is unsurprising, but it is the mischaracterization of the crisis by liberal politicians that is arguably most disturbing, empty expressions of sympathy and solidarity that illustrate the utter failure of the United States government at all levels. Indeed, liberal Democratic officials are also responsible for the dispossession of the vast majority of Americans who struggle to make a living in “Blue States.” The false dichotomies of peaceful vs. violent protesters; good cops vs. bad cops; and the undue attention focused on looting by real and imagined “outside agitators” illustrates yet again the inability of the Democratic Party leadership to understand the gravity of the situation facing black, Latinx, immigrant and poor working class communities of this country. One cannot stand against the racial injustice made clear by the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and countless others, while putting the interests of the police and private property ahead of the interests of people.

Protest, the Press and the First Amendment Imperiled

The time for the old liberal good cop/bad cop, protester/looter framework has passed. The clear evidence of the COVID-19 virus’s disproportionate impact on poor communities of color, the blatant disregard of the Republican-controlled federal government and the corporate bailouts provided by the CARES Act have convinced many Americans that they have little choice but to take their anger to the streets. How can government officials criticize the looting by protesters, when many of them handed over billions of dollars to corporations and minimal relief to those who are suffering from the virus and from years of racist disregard?

As in the 1960s, as historian Keeanga Yamahtta-Taylor has forcefully argued, the failure of the U.S. government to respond to the needs of the urban laboring majority has left “hundreds of thousands to take things into their own hands. It didn’t matter then, as it doesn’t matter now, whether white society approves or disapproves; what mattered was that formal mechanisms for social change failed to function, compelling African-Americans to act on their own behalf."

Rather than portray these protests as acts of lawlessness and criminal activity, the current protest movement can be seen as a part of the continuum of solidarity that has emerged in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008, the rise of immigrant rights mobilization and the Black Lives Matter Movement. They also are products of the daily acts of solidarity and mutual aid that have enabled under-resourced communities to endure amid the COVID-19 pandemic. The mobilizations of the past week are also manifestations of the unfinished revolution of the 1960s. The multiracial and cross-generational character of today’s protests resemble those that exploded on a smaller scale on the campus of Columbia University in April 1968, when privileged white and less-privileged black Ivy League students decided that their solidarity with the surrounding Harlem community and the people of Vietnam was more important than their own individual career advancement.

Our unprecedented moment requires political leaders to take unprecedented action. The time is now for the liberal leadership who govern blue state cities to step outside of history and defund the police and curb police power and stand firmly in solidarity with the protesters who are remaking democracy in the streets.

Frank Guridy, associate professor of History and African American Studies, specializes in urban and sports history, 20th century social movements and the history of the African Diaspora in the Americas. His forthcoming book is The Sports Revolution: How Texas Changed the Culture of American Athletics (University of Texas Press, 2021).

Rage Is No Strategy

By Wilmot James and Charles V. Hamilton

Nelson Mandela went on national television on April 10, 1993, to plead for calm after Chris Hani, the black leader and ally in the fight against apartheid, was assassinated by right-wing zealot Janusz Walus. Negotiations in South Africa had stalled, the country was on knife edge, everyone feared widespread anarchy, and Mandela rose to the occasion and reached out to "every single South African, black and white, from the bottom of my heart."

The day Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968, at the hands of convicted felon James Earl Ray, Robert Kennedy, a senator running for president at the time, was on a campaign stop in Indianapolis and faced a largely black audience with the horrific news. Kennedy said that he understood the anger, but appealed to black people not to feel hatred for all white people and to make an effort to go beyond these difficult times.

Mandela and Kennedy articulated with unquestioned authenticity an understanding of the hurt and rage of the people. “I had a member of my family killed,” Robert Kennedy said referring to his brother John, and “feel in my own heart the same kind of feeling.”

They did not want racial incidents in their respective countries to drive a wedge between people they knew had to unite and build together. Mandela specifically pointed out that a white Afrikaner woman had reported the assassin—a Polish immigrant whom today is lionized in contemporary Poland—to the police for gunning down Hani.

Sixty Years Later, We Need a New Brown

Historian Arthur J. Schlesinger Jr., once wrote in Cycles of American History that the purpose of democratic leadership is to establish ordered liberty in a sea of everlasting change. The United States in the late 1960s and early 1970s, South Africa in the 1980s and early 1990s, were moving through eras of upheaval where efforts to establish rights-based systems of "ordered liberty" could easily descend into licentiousness and chaos. The symbol of such descent is the burning and tearing down of the very community assets—a school, a clinic, a business—required to build a future. Asset destruction is the work of opportunists and hooligans who exploit genuine protest, peaceful activism and progressive militancy. For the builders of assets to triumph over the destroyers of assets requires strong leadership skills: Mandela and Kennedy in their time had lots.

Mandela, who sat in prison for 27 breathtaking years for a principle, was trained as a lawyer and commanded the respect of even his jailers. Kennedy came from a family of extraordinary leaders, served his brother as attorney general and led the fight for desegregation, civil rights and equality from the platform the federal government provided during a crucial period of U.S. history.

Henry Kissinger once said never build institutions around the character of great men and women, because in every generation we would have to find one.

In the burning chaos following the public death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, history calls for the rise of leaders who can turn racial rage into a strategy to rebuild the nation as a stronger and not a weaker democracy. In the midst of only the second most damaging pandemic in a 100 years, the immediate task must be to re-establish civic peace and unite the nation to single-mindedly focus on surviving COVID-19 with the people’s health and other assets intact.

Robert Kennedy visited South Africa in June 1966. He was not welcomed by the apartheid government—a badge of honor—but they could not refuse him entry. He delivered a remarkable tribute to the desire all human beings have to be free and is well remembered for quoting Archimedes’ ringing declaration: "Give me a place to stand and I will move the world."

Kennedy inspired all freedom loving people to not yield to futility in the face of cruel governments. He warned against the dangers of expediency. He affirmed bold democratic leadership and highlighted the dangers of timidity. He joined Mandela and other great democratic leaders who had that special ability to convert protest into strategy and the charisma to convince millions of people that finding ordered liberty in a world of everlasting change is something worth having and fighting for. Would such leaders rise to the occasion today.

Wilmot James, a former South African Member of Parliament and co-editor of, and contributing author to, Nelson Mandela in his Own Words, is a Visiting Professor of Political Science at Columbia University. He teaches a course on Global Health Security and Governance.

Charles V. Hamilton is a veteran academic activist, co-author of Black Power (with Kwame Ture, formerly Stokeley Carmichael) and an Emeritus Professor of Political Science at Columbia University.

This column is editorially independent of Columbia News.