Are We Ready for Designer Babies?

A Columbia psychiatrist and ethicist addresses the quandaries we face over the changing ways we create children.

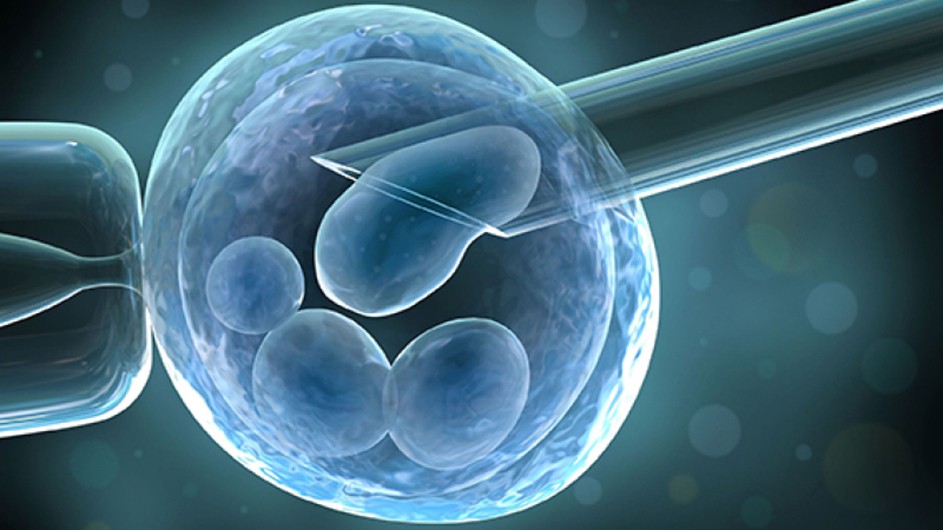

Since the 1978 birth of Louise Brown, the first “test tube” baby, reproductive technologies – such as in vitro fertilization, artificial insemination, assisted hatching of embryos – have expanded enormously, creating more than a million infants.

About 20 percent of American couples now use infertility services to help them conceive, and that number is growing.

In his new book, Designing Babies: How Technology Is Changing the Way We Create Children (Oxford University Press, October 2019), Robert Klitzman, a professor of psychiatry and director of Columbia’s Master of Science in Bioethics, tackles this brave new world of assisted reproductive technologies and the ethical, legal and policy issues they raise.

“For couples struggling to become parents, for women who delay childbirth, and for gay and lesbian couples, reproductive technologies can be miraculous,” said Klitzman. “But they also pose psychological and moral dilemmas that have not received enough attention.”

While the European Union and other industrialized countries closely regulate this area, in the United States, many observers call the IVF industry "the Wild West," Klitzman said. The U.S. is one of only three countries that legally allows adults to buy and sell human eggs.

Columbia News spoke with Klitzman about his concerns surrounding today’s baby-making.

Q. What led you to write Designing Babies?

A. Several years ago, I wrote a book, Am I My Genes? Confronting Fate and Family Secrets in the World of Genetic Testing. I interviewed men and women at risk of several diseases for which few predictive genetic tests existed. One woman, who had the gene that causes Huntington’s Disease, told me that the biggest issue she faced was whether to remain childless, or get pregnant and test the fetus and undergo an abortion if she had the gene. Alternatively, she could screen embryos and discard those with the gene or buy another woman’s eggs. “But if I do this,” she said, "what am I saying about the value of my own life? I would have been aborted!” Her question troubled me. It raised important issues about how technology was posing dilemmas about the quality and meaning of being alive.

Then, a few years later, a friend asked me if I wanted to father her child, if I wanted to be a sperm donor. I had known her for years, but we weren’t very close. Still, she said, I’d “be perfect.” I thought about it, and eventually declined, but became even more interested in the assisted reproductive technology industry and how people were making all of these varied decisions. I began to conduct research and eventually wrote this book.

Q. What are your worst fears about assisted reproductive technology? How far is too far?

A. I am concerned that these technologies are advancing far beyond our understanding of their ethical, legal and social implications. Last year, a scientist in China announced that he had edited genes in embryos, using CRISPR technology, and produced twin girls. Gene editing has enormous potential risks. It could eventually be used to eliminate mutations that cause disease but could, in the future, also take out or add genes associated with traits deemed socially desirable or undesirable, such as hair color, eye color, height and intelligence.

This would constitute eugenics, which the Nazis pursued with horrific results. I am also concerned that the relatively unregulated IVF industry could end up using such a technology with little oversight. Assisted reproductive technologies already in use remain expensive, which means only the wealthy people have access to them.

Q. If you knew someone struggling with infertility what suggestions would you have for them?

Reproductive technologies have aided millions of people, but I would encourage patients to anticipate that the journey may be long and complicated. Having a child can give great meaning to life, but it can lead people to ignore some of the limitations and risks of these procedures.

Prospective parents should also realize that most IVF cycles fail to produce a live birth, and that the rate of failure increases with age. They commonly avoid using another woman’s eggs but may want to consider doing so if they want to get pregnant. Many parents who use a stranger’s eggs or sperm plan never to tell their child, because they fear he or she will feel less loved. But their child, as an adult, may undergo genetic testing and find out, and feel betrayed.

Patients and others should recognize that we can change our definitions and understandings of "motherhood," and "fatherhood." The processes can all be emotionally difficult, and being prepared for that, and having social support can help, too.