The Department of Art History and Archaeology Receives A Major Grant from the Getty Foundation

Professor Avinoam Shalem will co-direct Black Mediterranean, which reconsiders the history of the relationship between Africa and Europe.

The Department of Art History and Archaeology recently received a major grant from the Getty Foundation for the multiyear project, Black Mediterranean/Mediterraneo Nero—Artistic Encounters and Counter-narratives/Incontri Artistici e Contronarrazioni—as part of the Getty’s Connecting Art Histories initiative.

Black Mediterranean is a joint project between Avinoam Shalem, the Riggio Professor of Art History, Arts of Islam, and Alina Payne, the Alexander P. Misheff Professor of History of Art and Architecture at Harvard University, and the director of Villa I Tatti, Harvard’s Center for Italian Renaissance Studies in Florence, Italy.

The project’s mission is to reconsider the histories and historiographies of the Mediterranean, paying particular attention to African influences on Mediterranean cultures. The project encompasses the major centers and routes between Europe and Africa along the Mediterranean coasts, while also exploring routes and crossroads connecting central Africa to the Mediterranean within three main zones: east, central, and west Africa.

Shalem discusses Black Mediterranean with Columbia News—how the project developed and its scope, both historically and in terms of current events.

Q. How did this project come about?

A. The project was a result of my interest in the production of works of art by European artists of the 16th and 17th centuries, like Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) or Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen (1504-1559). They visually documented a less-remembered Mediterranean episode—the conquest of Tunis, on the coast of North Africa, in 1535 by the Habsburg monarch Charles V.

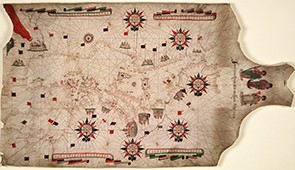

I was struck by the large amount of artistic attention given to this relatively short moment of Western power in Africa, and the relatively small space it occupies in the long histories of Mediterranean battles—all of which aimed for the hegemony and control of the movements of goods and people. Situated at the very heart of the Mediterranean, and controlling the naval flow between the western and eastern parts of the sea, as well as the naval route from Africa to Italy, Tunis was one of the important strategic sites in this fluid landscape.

As my interest grew, many other art objects associated with this specific Habsburg battle were rediscovered. They ranged from paintings and prints of the protagonists of this epoch, monumental tapestries that depict the grand battles of Charles V in North Africa, lavish arms and armor, carved rock crystals and wood panels, and, no less compelling, looted Islamic artifacts, especially illuminated Qurans.

Though the occupation of Tunis by the Habsburgs lasted only from 1535 to 1574, the fall of the city at the hands of Charles V marked a turning point in the histories of East-West interactions. The engagement with Tunisia’s classical past—for example, the archaeological ruins of Carthage and the Roman amphitheater of El-Jem—initiated a novel scientific and historical opportunity for studying these spaces. This antiquarian approach of the 16th century went beyond the common Orientalist vision, recalling, to some extent, Napoleon Bonaparte’s “rediscovery” of the ancient ruins of Egypt at the end of the 18th century.

Q. What is the goal of the project?

A. This project critically revisits the histories and historiographies of the Mediterranean. The long story of world civilization—for which the Mediterranean was, and still is, a hub—has usually been woven by quasi-horizontal and parallel vectors that move alternately between East and West. Incorporating into this field the African continent, we move beyond the west-east patterns that shaped and controlled the writing of Mediterranean art history.

Thus, Black Mediterranean places again the sea as the medial space for artistic interactions, but adds to it the north-south longitudinal meridians. The project is a corrective methodological tool that aims to include forgotten narratives and to revisit historiographies of racial subordination. It provides a forum for art historians to address overlooked Afro-Mediterranean chronicles, and is a call for a new critical humanism that revisits Mediterranean histories to offer better insights into past empires and colonial affairs. By reexamining these accounts, we can reframe Western hegemonic, epistemic control of the past. Terms such as Afro-American and Afro-European could be reconsidered around histories of Eurafrica.

Moreover, with Black Mediterranean, we hope to establish cooperation with mainly young and promising scholars in Africa, especially in countries where art history is an emerging discipline. Part of our goal is to build a regional network of academics, to foster collaboration among different art historians’ fields and areas of expertise.

Q. What is the historical time frame that the project encompasses?

A. The project mainly focuses on about 600 years of history, from 1500 to the present, though trajectories that stretch back from premodern and modern times to the ancient and medieval Mediterranean world are welcomed, too.

Q. What parts of Africa will the project focus on?

A. In general, three vertical routes will be the focus: the eastern African route that moved from Ethiopia to Alexandria via Cairo (with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 as its culmination); the central sub-Saharan route that travels north to Tunis and Italy via Sicily (with the 1535 conquest of Tunis by Charles V and the 1571 Battle of Lepanto serving as anchors); and the west African route along the Atlantic coast, concentrating on the age of Portuguese expansion in Africa (circa 1415-1600).

Q. What will you specifically be teaching and/or researching as part of this project?

A. In the fall of 2022, I will teach a graduate seminar on Black Mediterranean. This course seeks to call our attention to the important artistic and cultural role played by Africa in shaping Mediterranean aesthetics and, paradoxically, the continent’s absence from most Mediterranean studies to date. While concentrating on the movement of artifacts, artisans, persons of power, and slaves, as well as revisiting trade routes and military conquests, the class will unveil the constant and mutual transfer of knowledge.

We will discuss various historical moments, such as the transfer of the relics of Saint Mark from Alexandria to Venice, the boom in the import of ivory from sub-Saharan Africa to Europe, the introduction of the Almohads’ aesthetic in Spain, as well as trading throughout the Mediterranean during the Fatimid period (around 1000 CE).

Also, moments of artistic transfer to, rather than from, Africa will be highlighted, including the introduction of the Abbasid royal aesthetics of Baghdad in North Africa, the settlements of Amalfitan traders in Fatimid Egypt, the Norman looting of Tunis around 1200, Jesuits in Ethiopia in early modern times, and, back to where the project started, the Habsburg conquest of Tunis in 1535.

Q. Will Black Mediterranean touch on current migration issues between Africa and Europe via the Mediterranean?

A. Indeed. The project already does. In February, I engaged Anthropology Professor Naor Ben-Yehoyada and Youssef Ben Ismail, a Mellon SOF/Heyman and MESAASlecturer, to interview the Algerian artist Rachid Koraïchi about his project, Jardin d’Afrique, in Tunis. For this work, Koraïchi designed and built a shrine and cemetery for the bodies of anonymous migrants who died crossing the Mediterranean from Africa to Europe.