Moving Toward a Feminist City

What does a women-centric future look like, and how do we build communities of care?

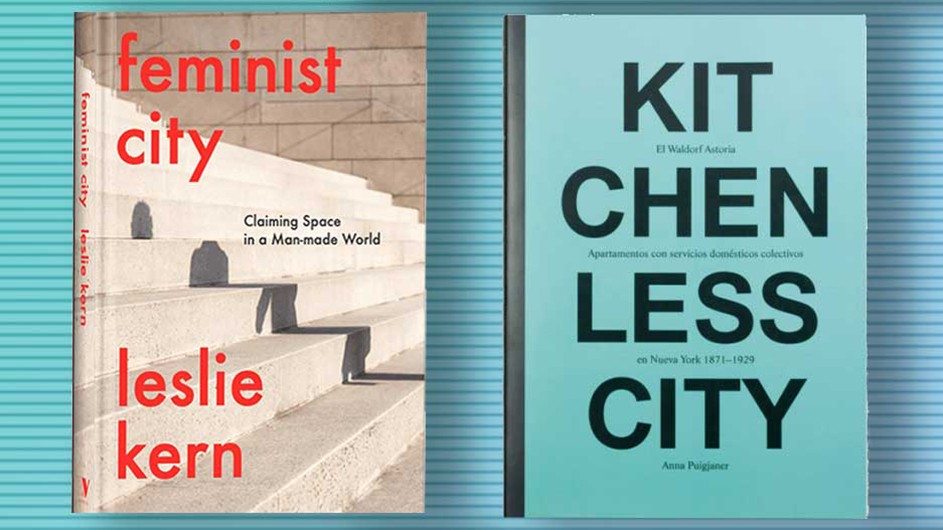

On October 2, 2020, the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation (GSAPP) and the Institute for Research on Women, Gender, and Sexuality cohosted The Feminist City. Taking its name from Leslie Kern’s recent book, the event featured a conversation between Kern, an associate professor of geography and environment, and director of the Women's and Gender Studies Program at Mount Allison University in Canada, and GSAPP Professor Anna Puigjaner. Jack Halberstam, a professor in the Department of English and Comparative Literature, moderated the discussion.

GSAPP Dean Amale Andraos offered introductory remarks and framed the event as an opportunity to explore the question: What does a feminist future look like, and how do we build communities of care?

Kitchenless City

For Puigjaner, the answer lies in the intersection of productive and reproductive labor in the home. Her talk followed the sequence of her forthcoming book Kitchenless City, which traces the emergence of a New York City housing typology with collective amenities at the beginning of the 20th century. The detachment of the kitchen from living units in these buildings, she argued, is relevant today: “It’s important to keep talking about architectural proposals that try to reshape enclosures based on race, gender, age, and class.”

These so-called hotel-apartments emerged as a response to the poor state of tenement housing in 1871, and experienced a boom after 1901 before construction decelerated due to restrictions imposed by housing laws enacted in 1929. The collective spaces enabled a wider segment of the population to access affordable domestic services since costs could be shared among all of the residents. “The growing culture around industrialization invited one to think about the value of the collective not only as a force of production,” stated Puigjnaer, “but also as a way of living.”

Shifting to the present, Kern began her talk with recent Canadian news headlines related to COVID-19 and care issues. “Even in a country where they say that the pandemic has been handled relatively well,” Kern said, “these kinds of gendered and racialized care labor problems persist. What this suggests to me is that there are a whole lot of assumptions still underlying the way that we set up our cities and our homes, and a whole lot of being okay with relying on a very shaky, unequal, and exploitative status quo.”

Although exacerbated by the pandemic, the care crisis results from many longstanding issues, including the invisibility of care work undertaken in private homes, the imbalanced gender division of childcare and housework, the undervaluing and stigmatization of public care work, and rampant assumptions about who is responsible for care work across policymaking sectors. “The fact that some people seem to be hearing about ... these things for the first time in their lives,” said Kern, “says a lot about how power works to hide all of the things that are existing to support power and privilege.” To envision a feminist city amid these obstacles, Kern proposed the adoption of new assumptions—the minority is the majority, and the niche is the whole; home is not what we think; people have bodies; and care work is the economy.

From Building to Unbuilding

Halberstam then circled back to Dean Andraos’s initial question, and suggested shifting the focus from building to unbuilding, referencing his research, which applies the term “unbuilding”—borrowed from the vocabulary of artist Gordon Matta Clark's and the artists group Anarchitecture’s practices during the 1970s—to contemporary queer theory. “We shouldn’t just be building a gendered city,” Halberstam argued: “We should also be unbuilding patriarchal systems, foundations, and subsystems that invisibly support a city through which white men move easily.”

In response, Puigjaner said that although hotel-apartment buildings succeeded in redefining reproductive labor and deconstructed gender divisions, they ultimately generated other divisions along class and race lines. She discussed how crises have triggered movements of collectivity, such as the 2008 financial crisis giving rise to the collective kitchen movement in Peru, which enabled women to achieve political voices.

Unbuilding the home, Kern added, would require society to unbuild tax code, property law, and citizenship law, among many other rules and regulations. This process, she agreed, is critical: “The family and its confinement in this space that we call the home ... is used as a weapon against people who don’t fit into those norms. It’s a boundary that includes and excludes people from all sorts of social resources.”

“Little steps, architecturally speaking, toward that direction” of inclusion, Puigjaner summed up, “would help us to start understanding our home not as a fixed entity, but something that is much more open and diffuse, and in which limits are blurred. In the future, we will understand that the home is our city at large.”