Latinos Left Behind by Media Mergers, Finds Study Led by Frances Negrón-Muntaner

Frances Negrón-Muntaner, director of Columbia’s Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race and founder of the Media and Idea Lab, has been writing about media and race for 20 years. In her latest study, The Latino Disconnect, she investigates why Latinos are disproportionately underrepresented in mainstream entertainment and news coverage.

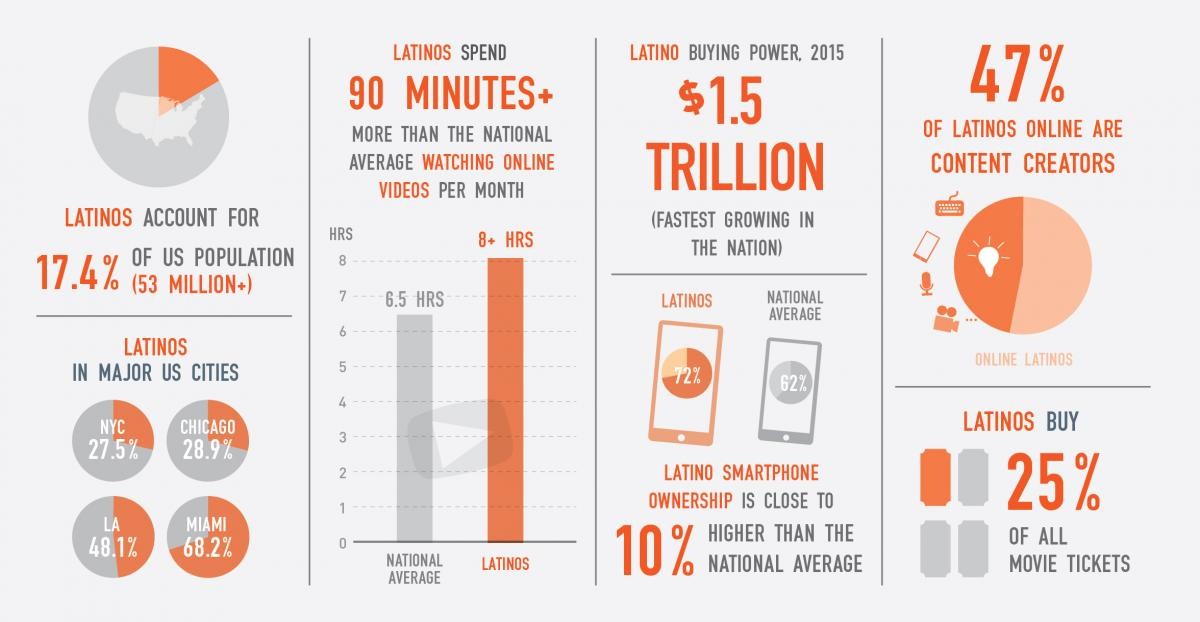

Hispanics currently make up over 17 percent of the U.S. population, about 55 million people, up from 35.7 million since the year 2000. But they represent between two to eight percent of the television and movie industry, the study finds

“If over a period of 10 years the pattern stays the same even as the Latino population grew substantially, something is going on,” said Negrón-Muntaner, who is also an associate professor of English and comparative literature and an award-winning filmmaker.

A part of that something, she believes, is the ever-larger media conglomerates that result through corporate mergers. “The companies formed in these transactions do not typically include Latinos in decision-making, hiring, and storylines of their shows,” she said. “This is not just a cultural issue, it’s political and economic.”

Q. What do media mergers have to do with ethnicity, particularly Latinos?

A. Latinos pay an enormous amount of money for entertainment and consume media at higher rates than other ethnic and racial groups. For instance, while Latinos comprise 18% of the population, they buy 26% of movie tickets. Yet they are severely underrepresented as on-camera and behind-the-camera talent, and in the C-suite of all mainstream studios and networks. In addition, when there’s a merger between a cable and a content-producing company, the newly-formed corporation tends to promote its own productions rather than content produced by independent companies headed by people of color, including Latinos. This makes it harder for companies to get sustainable carriage fees and survive. In the end, the smaller providers will likely disappear or be bought out by larger companies.

Q. Does the fact that that there are visible Latinos in entertainment and on news shows make a difference?

A. Yes, but the presence of a few major stars in entertainment – there are next to no Latinos in national news – may also obscure the larger picture. In other words, because Sofia Vergara and Jennifer Lopez occupy so much public space, their fame gives the impression that there are more Latinos in media than there actually are. Similarly, the press and executives will often point to the existence of Spanish-language networks to argue that Latinos are well represented in the media. But while there are a range of Spanish-language networks, and some like Univision are very influential, they are not viewed by the majority of Latinos and are increasingly owned by non-Hispanic companies, where Latino input becomes diffused. In the study, I also found that the leaders of the Spanish-language companies folded into a merger don’t tend to become leaders on the English-speaking side. While the new company acquires diverse talent, the top leadership does not diversify.

Q. You've studied Latinos in media before, in your 2014 study, “The Latino Media Gap.” What is new in your current report?

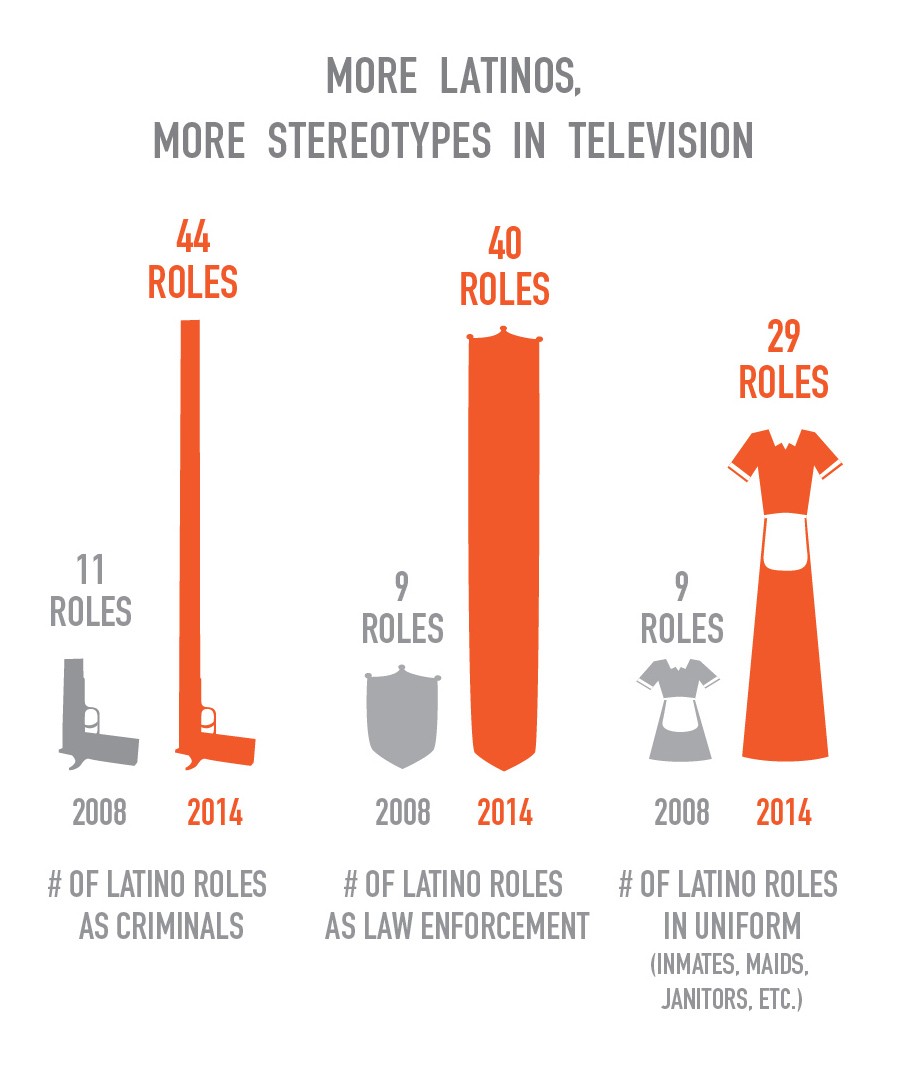

A. In addition to studying media and telecom company mergers and global internet streaming companies like Netflix, I took an in-depth look at news coverage. I found that in the more than 9,000 stories aired by one of the most influential network news programs from 2012 to 2014, only 292 stories, or 3 percent, contained US Latino and Latin America-related content. And of those, 64 percent of the stories were about crime or immigration. In this sample, Mexican and Puerto Ricans were the two groups most related to lawbreaking; 64.3% of Mexican-themed stories were related to drugs and illegal entry and nearly 89 percent of the stories about Puerto Ricans focused on either sex crimes or drug trafficking. This trend is common across all news providers and has been a steady pattern for several decades.

Q. How can this lack of diversity be addressed?

A. In one word: action. Both prior studies suggest that when consumers leverage their power and advocates organize, they are often successful, particularly in television. This is due to television’s business model, which greatly depends on domestic markets and advertisement. A recent example took place last year, when newscaster José Diaz-Balart’s show, “The Rundown,” was rumored to be cancelled from its weekday spot on MSNBC. Many Latino grassroots groups mobilized and reached out to NBC requesting that the only Latino lead anchor at the time stay on air. [The show is still on, and now is called “MSNBC Live with José Diaz-Balart.”]

Q. What are you working on next?

A. The third report will be about Latinos and comedy. This is important because while comedy has had, and continues to have, a major impact in shaping national conversations about political and cultural belonging of minority groups in the U.S., Latinos are largely absent. And when Latinos are present, they mostly play one type of role, the immigrant with a funny accent who doesn’t understand American culture. The result is that comedy reinforces the notion that Latinos are recent immigrants without deep roots or consequence to American history, politics, and culture. So, among the questions that I will be exploring are why does Hollywood think that Latinos are not funny and what are Latinos laughing at. Ultimately, I am interested in knowing what can laughter tell us about our collective selves.