A New Book Looks at the Life and Legacy of a Leading Iranian Thinker

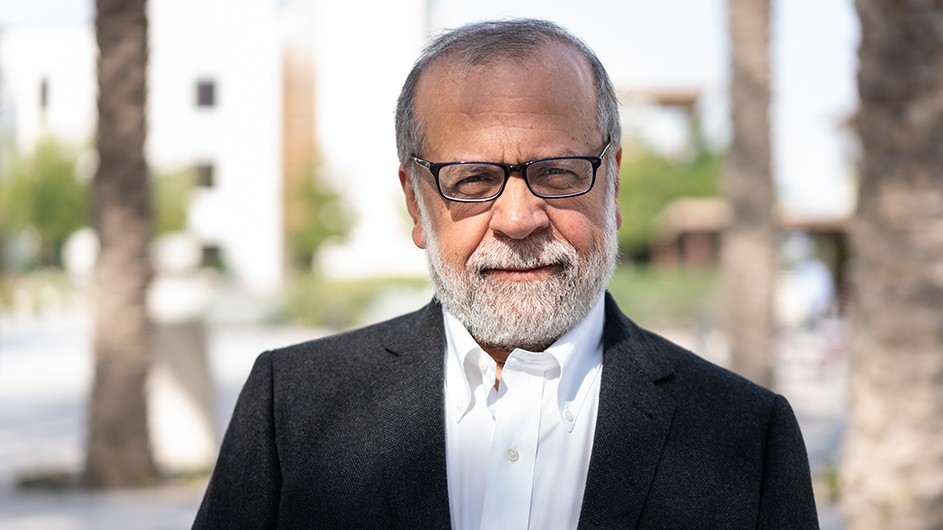

Professor Hamid Dabashi's biography of Jalal Al-e Ahmad introduces him to a new audience.

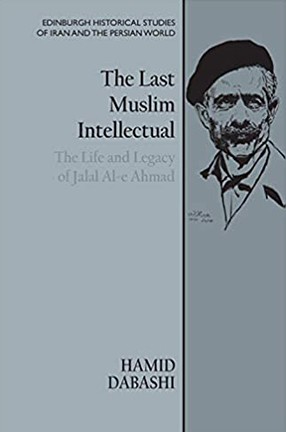

In this biography, The Last Muslim Intellectual: The Life and Legacy of Jalal Al-e Ahmad, Professor Hamid Dabashi, who teaches in the Department of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies, contends that Al-e Ahmad articulated a vision of Muslim worldly cosmopolitanism, before the militant Islamism of the last half a century degenerated into sectarian politics.

Dabashi discusses the book with Columbia News, along with the last great book he read, which subjects he wishes more authors would write about (Thomas the Tank Engine, Peter Pan, and Spiderman), and who his ideal dinner guests would be.

Q. How did you come up with the idea for this book?

A. I am now in the autobiographical phase of my scholarship. I just published On Edward Said: Remembrance of Things Past, which is a collection of my writings that has Said, a dear friend and former Columbia professor, at its epicenter. My new book on Al-e Ahmad is also autobiographical in the sense that Al-e Ahmad was a towering public intellectual of my early youth, the Edward Said of Iran, as it were, whom I never met in person, while Said was the Al-e Ahmad of my mature life. I needed to revisit Al-e Ahmad in the context of what we call the post-Islamist phase of political thought. I wished to retrieve the cosmopolitan worldliness of Al-e Ahmad’s life and legacy, which has been deeply overwhelmed, if not altogether lost, under the exhausted possibilities of militant Islamism, as it has degenerated into sectarian violence.

Q. What made Al-e Ahmad the "last Muslim intellectual"?

A. He was the last Muslim intellectual in the sense that he embodied the cosmopolitan worldliness of Islam of his time—an Islam that was conversant with the world, which we have now all but lost to pernicious sectarianism. As such, I place him next to leading American intellectuals like James Baldwin or German Jewish intellectuals like Hannah Arendt, Theodore Adorno, and Walter Benjamin. In effect, I appropriate Baldwin, Arendt, Adorno, Benjamin, and W. E. B. Du Bois for a renewed reading next to Said, Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, Muhammad Iqbal, and Léopold Sédar Senghor. I place Al-e Ahmad next to them to suggest and map out a sophistication hidden under the smokescreen of the fetishized binary of “Islam and the West.”

The book is therefore about Al-e Ahmad, but it is also about a whole world that extends from the Harlem Renaissance to the Negritude Movement, and also reaches to post-Holocaust critical theory, while placing a Muslim intellectual in this company. The very title of my book comes from a seminal text by Russell Jacoby, The Last Intellectual.

Q. Are there any lessons from Al-e Ahmad’s life that can be applied toward today's sectarian politics?

A. Indeed, there are—a fusion of his own fast-paced, short-lived, and insatiable curiosities, and the world that enabled and responded to Al-e Ahmad are what I retrieve and theorize in this book. The task is to overcome the false binary of “Islam and the West” that has plagued the world before and after the time of Al-e Ahmad. Paradoxically, he is best known for his essay, Gharbzadegi/Westoxication—which I read as a legitimate critique of colonial modernity and not a nativist treatise against “the West,” as the essay has been falsely read.

Equally important in Al-e Ahmad’s life was his wife Simin Daneshvar, who was a major literary figure in her own right. The recent publication of their massive correspondence, especially when she was a visiting scholar at Stanford in 1952, has given us astonishing insights into their married life. My book is the first full-fledged treatment of this new material and the nuances of their marital relationship.

Q. What books do you recommend for getting through the pandemic?

A. Only one—but what a book! Panchatantra if you read Sanskrit, its English translation if you don’t, or its 8th-century, Arabic rendition by the glorious Ibn Muqaffa’, which he called Kelilah and Dimnah. It is a collection of wonderful animal fables, which has graced generations of readers around the globe in multiple languages, full of wit and wisdom. It was my antidote to the daily newsfeed that came at us like a diabolic damnation while we were in quarantine. The stories are so beautiful, you can tell them to your children, as I did when my children were growing up; and yet so profound and powerful, you can teach them in a graduate seminar, as I did this past semester in my course on Islamic political thought.

Q. What's the last great book you read?

A. The ingenious moral philosopher Abu Ali Ahmad Miskawayh’s 11th-century Javidan Kherad/Eternal Wisdom. I love the catholicity of its learning, and its bringing together of Iranian, Greek, Indian, and Arabic wisdom literatures to inform a universal prose, without any prejudice or preference, and generating a cosmopolitan ethic of civilized life.

Q. What's your favorite book no one else has heard of?

A. Abd al-Rahman Jami’s glorious 15th-century poem, Salaman and Absal, which was translated into English by Edward FitzGerald, the famous translator of Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyat. But it’s not just the poem itself that is important; equally crucial is its long, winding history from probably Greek, Indian, or Hebrew sources to its Arabic translation in the 9th century. The poem tells the story of a prince born via artificial insemination—his father’s semen was placed inside a Mandragora plant—who grows up and falls in love with his wet nurse. Their story becomes the tragic alchemy of philosophical and mystical deliberations.

Q. What subjects do you wish more authors would write about?

A. Looney Tunes, Marvel Comics, Thomas the Tank Engine, My Little Ponies, Ninjago. I watched them with my children, and as I did, in my mind I was always writing about them. I was always frightened by Thomas the Tank Engine. He is a snitch for Sir Topham Hatt, the definition of the abuses of capitalist modernity, who disallows rest and leisure, and turns everyone into a “useful engine.”

The same is true of Spiderman, a far more entertaining, yet frightful version of the idea of the end of history, with a heavy dose of Freudian patricide woven into it. I have written about Spiderman. I wish more authors would now write about Peter Pan, and the crucial nocturnal journey of those kids from childhood to adulthood. There is, of course, a massive body of literature on this, but there is still much more to think through and write.

Q. Do you read actual books or do you use an e-reader?

A. Books. I can’t stand e-readers. I am very tactile with my books. I write notes in them with multiple colors coded for various purposes. I fall asleep with the books, and start dreaming about them. Then I wake up and don’t remember my dreams, and keep reading the books. I keep the receipts from where and when I bought them.

In effect, I turn my books into medieval manuscripts with texts and marginalia—through various versions of me: my youth, adolescence, older age. I have books with three or four generations of my marginalia in them.

I am always hunting for PDF copies of old, rare books and manuscripts, which, especially during this pandemic, have been a blessing. I can’t travel to libraries, so through PDFs, libraries travel to me! I always tell my students to do as I do: Think more than they read, read more than they write, write more than they publish!

Q. What are you teaching this term? How are you helping your students cope with online learning?

A. I have just been appointed the director of undergraduate studies for my department, so I am teaching the honors seminar for our senior undergrads. I get to guide a band of utterly brilliant students as they do original research!

There is, of course, no substitute for in-person classroom learning, but we do the best we can to turn the online classes to our advantage. Paradoxically, I always told my students to put their devices away, for unless I looked them in the eye, I could not teach them anything. Now, those devices are my own eyes into their minds. The effects of online teaching on our pedagogy are yet to be assayed. We are in the midst of a historic epistemic shift in education. I can’t wait for in-person classes to resume, but I am not sure if we will ever go back to the classical Socratic method or peripatetic philosophizing. I habitually walked around my classrooms as I lectured. This is a whole new mise-en-scène of trying to sit down and stare into my laptop and teach.

Q. You're hosting a dinner party. Which three academics or scholars, dead or alive, would you invite and why?

A. The very idea of a dinner party is so alien in these days of social distancing and physical isolation, I don’t know if I am capable of being a gracious host anymore. If I were to collect my wits across time and space, I would love to host the sublime Persian political satirist of the 14th century, Ubayd Zakani, and the New Yorker’s Andy Borowitz. I’d do the cooking and translating. So not academics, but satirists, in gratitude to both of them for helping me survive the last four years of deceitful and cruel politics.

The following week, I’d invite the late Japanese filmmaker, Akira Kurosawa, and the master Persian epic poet, Ferdowsi, for dinner, and share with them how they are identical in their camerawork when “shooting” battle scenes. Kurosawa would be flabbergasted to find out that more than one thousand years before he shot his Ran or Kagemusha, there was a Persian poet who composed his epic battle scenes similarly.

Check out Books to learn more about publications by Columbia professors.