A New History of Black Creativity and Aesthetics

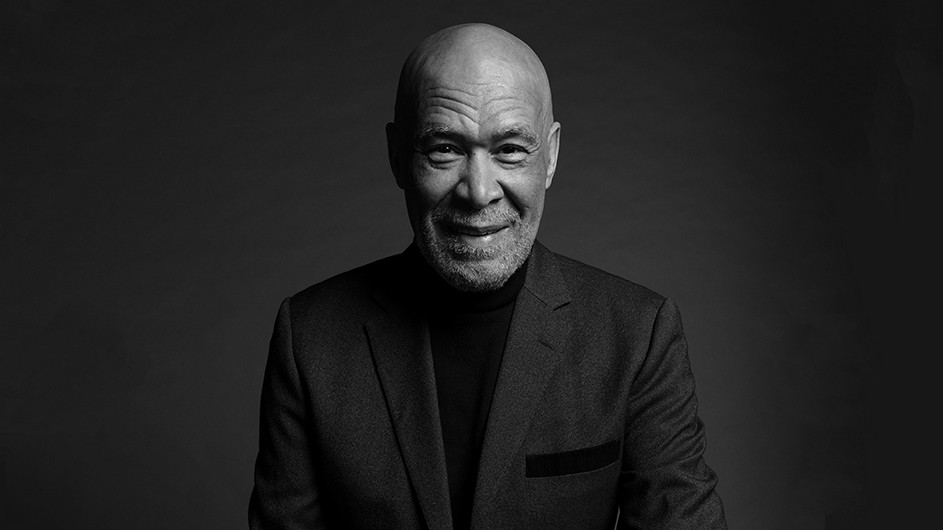

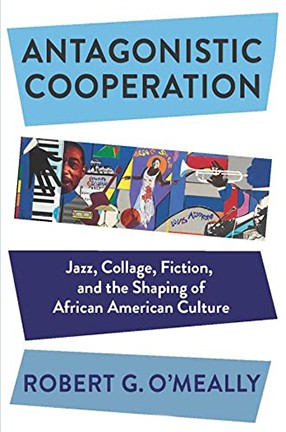

In “Antagonistic Cooperation,” Professor Robert O’Meally explores everyone from Bearden and Basquiat to Ellison, Morrison, and Ellington.

Ralph Ellison famously characterized ensemble jazz improvisation as “antagonistic cooperation.” Both collaborative and competitive, musicians play with and against one another to create art and community. In his new book, Antagonistic Cooperation: Jazz, Collage, Fiction, and the Shaping of African American Culture, Robert O’Meally, Zora Neale Hurston Professor of English and Comparative Literature, shows how this idea runs throughout 20th-century African American culture to provide a new history of Black creativity and aesthetics.

From the collages of Romare Bearden and the paintings of Jean-Michel Basquiat, to the fiction of Ralph Ellison and Toni Morrison, and the music of Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, O’Meally explores how the worlds of African American jazz, art, and literature have informed one another. He argues that these artists drew on the improvisatory nature of jazz and the techniques of collage not as a way to depict a fractured or broken sense of Blackness, but rather to see the Black self as beautifully layered and complex.

O’Meally talks about his new book with Columbia News, along with what moves him most in a work of art, classic novels that he’s only now reading for the first time, and who he would like to sit across from at a dinner party.

Q. How did you come up with the idea for Antagonistic Cooperation?

A. The idea for the book crystallized at a concert featuring an exchange of choruses by two great tenor sax players, Branford Marsalis and Joe Lavano. The exchange started off routine, a crowd-pleasing jam session. But gradually, their playing became more and more heated, with both musicians reaching inside themselves to play directly from the heart. To tell the story, as jazz players often say.

Into this suddenly exalted conversation in music, a very Niagara Falls of ideas was released. After the show, backstage, they were hugging one another (and muttering affectionate curses: “You ole mutha!”). It was true brotherly love—antagonistic cooperation!

Q. Do you think that the work of contemporary Black artists is influenced by the 20th-century African American jazz, art, and literature that you discuss in the book?

A. Yes. I’m not surprised any more when a hip-hop artist quotes a phrase by Dexter Gordon, or a young dancer refers to a mood or a character from Toni Morrison as an inspiration.

Q. What moves you most in a work of art, be it a piece of music, a book, or a painting or sculpture?

A. I’m very moved by any artist’s palpable sense of commitment to a work. Whether via spareness of detail, harmonic mashups, or unexpected juxtapositions of color or texture, I love to feel the artist’s body-deep urge to convey experience, emotion, and thought.

Q. Are there any classic novels that you have only read recently for the first time?

A. I’d never read The Three Musketeers or The Count of Monte Cristo until spring break this year. Now I’m working my way through all of Alexandre Dumas—a tremendous treat!

Q. What are you teaching this semester?

A. My intro to African American writing includes sections on Langston Hughes and Roy DeCarava, August Wilson and Big Bill Broonzy, Alma Thomas and Zora Neale Hurston, Duke Ellington and Toni Morrison, and Shakespeare.

Q. You’re hosting a dinner party. Which three academics or scholars, dead or alive, would you invite, and why?

A. Thelonious Monk, Zora Neale Hurston, and French writer-philosopher Édouard Glissant. I’d also invite e.e. cummings, and ask them all to discuss cummings’ assertion: “Damn EVERYTHING, but the circus!”