Portrait of a Marriage in Mussolini’s Italy

What does a relationship between an American woman and her Italian military husband tell us about the pervasiveness of fascism under Mussolini?

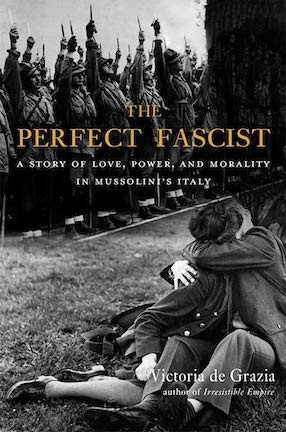

A beautiful American opera singer falls in love with and marries a handsome older Italian solider and politician. That description could be the start of a romance novel, but it is definitively not in Victoria de Grazia’s The Perfect Fascist: A Story of Love, Power, and Morality in Mussolini’s Italy. De Grazia, a professor in the department of history, uses the relationship between Lilliana Weinman and Attilio Teruzzi to illustrate how Mussolini’s fascist regime infiltrated all aspects of Italian life.

Columbia News recently spoke to Professor de Grazia to find out how an American Jewish woman ended up marrying an Italian fascist and how Italian fascism mixed the political with the personal.

Q: You mention in your prologue that relatives of Weinman approached you to write this book to find out why “this self-assured woman from a good Jewish family” would marry Teruzzi, "an old and bearded fascist." Why do you think she did?

A: Lilliana Weinman originally went to Milan, the center of world opera at the time, to train as a prima donna. Her plan was to study for three years, return to New York City, take the Metropolitan Opera by storm, and become a great diva. Her talent was such that she might have succeeded had not Teruzzi come into her life. He courted her like he was organizing a coup: inviting her to meet the fascist top brass, showing up at her hotel in full dress uniform, overwhelming her parents with attentiveness. Ultimately, she would forsake her career as prima donna on the opera stage for what she mistook to be real life, as wife and muse to a fascist celebrity.

Q: How did examining Teruzzi’s private life help you understand fascism and Italian society under Mussolini?

A: Fascist despotism mishmashed personal life and politics in an especially heartless way. Fascists were passionate in proclaiming their love for the nation, for Il Duce, and as comrades in arms, for one another. Soldiers, like Terruzzi, who switched their loyalties from the military to the black shirts brought the violence of war and archaic notions of military honor, glory, and betrayal to the home front—meaning both to their homeland and their households. These were not strong men, but weak men who cocooned themselves in the power conferred on them by rising up the fascist hierarchy, who depended on their families, cliques, and Mussolini’s approval for the ballast to survive in the dog-eat-dog world of fascist politics.

Q: What parallels can be drawn between Italy under fascist rule during part of the first half of the 20th century and what is happening today in the United States?

A: What resonates to me from both eras is the big picture: the liberal world order in chaos. With the political system at an impasse in Italy in the early 20th century, political fortune seekers broke all the rules to grab power, denounced the old liberal establishment as geriatric and the so-called Reds (mostly Social Democrats), as enemies of the nation. The goal, allegedly, for these radical opportunists was to make the nation great again. The means were violent—smashing the unions, outlawing the opposition, and using executive power to steal elections, but also pandering to the traditional elites. The upshot was the restoration of order of a kind, but it was too unstable to last, short of even more abuses of power, which were legitimated by mobilizing public opinion against internal enemies and war mongering.

Q: Now that you’ve finished writing this book, hopefully you have time to read for pleasure. What’s on your list of books to read?

A: At the moment, I’m only interested in reading melancholy mixed genres like Javier Cercas, the Catalan novelist’s,The Imposter, which I just finished, and thoughtful history, like Margaret MacMillan’s War: How Conflict Shaped Us, which I just began. Also, books about beautiful things are capturing my attention—currently Penny Sparke, the British art historian’s 1970s, ever fresh, gorgeously illustrated Design in Italy.

Q: You're hosting a dinner party. Which three scholars, authors, activists, artists, or even celebrities, dead or alive, do you invite and why?

A: I’d have the quick and the dead—revived to what they were circa 1968, when the world spirit was thinking beyond the wretched Cold War, about alternative political systems, inequality, ending war, and the health of the planet. Can you imagine Zhou Enlai, the People’s Republic of China’s greatest statesman, also a lady’s man, reflecting on the world and the West, together with Simone de Beauvoir, old Europe’s leading feminist: can we know what humanity is without knowing the half called Woman? And bring in Angela Davis, fresh out of Berkeley and Frankfurt, a fierce mind and passionate to struggle for our homeland, the United States, to get on the side of the good fight. I wouldn’t have gotten in a word. But we all would have drunk a lot, raged at the world, reaffirmed our faith in humanity, the people, as we used to say then, and left the table with high hopes.