An RBML Program on Jewish Life in France Before World War II

A March 27 Rare Book and Manuscript Library discussion will focus on recently uncovered materials from the Zosa Szajkowski Archive.

On March 27, at 4 p.m., the Rare Book and Manuscript Library will present one of its Curatorial Shorts, conversations between curators and researchers about new findings from the library’s collections. The program will feature Michelle Margolis, the Norman E. Alexander Librarian for Jewish Studies at Columbia Libraries, and Daniela Goodman Rabner, who graduated in 2022 from Barnard, where she majored in history and Jewish studies.

They will be discussing drawings and documents that came to light recently in the RBML’s Zosa Szajkowski Collection, an assortment of material put together by Jewish historian, archivist, and bibliographer Zosa Szajkowski (1911-1978). Included are organizational records, papers, correspondence, periodicals, and printed ephemera related to East European Jewish life in France in the 1920s and 1930s, and in the territories of modern Ukraine, Lithuania, Poland, and Russia in the first quarter of the 20th century.

Goodman Rabner, who recently started work on a Fulbright research grant in Argentina, talks about the archive and the March 27 event with Columbia News.

How and when did you become involved with the Szajkowski Archive?

My involvement started during my senior year at Barnard, when I reached out to Michelle with the hope of working on Yiddish archives at Columbia. She placed me on the Szajkowski processing team under Katia Shraga Davydenko, an RBML archivist.

What did your work entail?

As Katia always says, processing a collection is the art of making order out of chaos. Processing this archive—one marked by Szajkowski’s tendency to collect everything and anything—required the establishment of both intellectual and physical control, and order. I began with the work on the archive that had been done by Sandra Chiritescu, a PhD candidate in Yiddish Studies at Columbia.

Over time, I assembled an understanding of the stories found within the archive. As I identified more and more of the material, these stories—hidden in a veil of mystery—began falling into place. I gradually realized that we were sitting on the entire remaining archive of the French branch of the Kultur Lige (a transnational Yiddish cultural organization), which resulted in two new authority subject records being submitted to the Library of Congress.

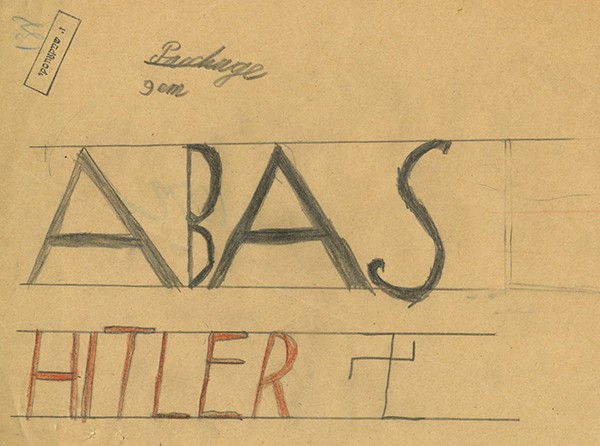

The processing of the archive took from April to August of 2022, culminating at the end of the summer in the anti-fascist childrens’ drawings currently on display at the RBML. It’s an exciting way to share this project with the larger Columbia community.

How did this project affect you?

My involvement with the RBML further exposed me to the wonders of library science and archival efforts. Archivists are hidden workers whose labor and knowledge open the floodgates of access without much recognition, and I feel so grateful to Michelle and Katia for all their guidance.

In the field of Jewish studies, library and archival work plays an active role in the preservation and protection of the Jewish past. The Szajkowski Collection, inherently, is the material product of Zosa Szajkowski’s wild ride as a World War II veteran, Holocaust survivor, stubborn, self-made scholar, and eventual alleged archive thief. Before he stole Jewish materials from European archives after World War II, he was an active member of interwar Yiddish Paris, who wrote extensively for the Naye Prese, a daily, Yiddish-language Communist newspaper published in Paris, about East European migrant conditions in France.

The archive deeply impacted my relationship to Yiddish history and collections, as it is an incredibly rich source of mainly Yiddish Communist culture and language, focusing on a dynamic chapter of that world that is often overshadowed and understudied. It’s gratifying to think about the many pathways of inspiration and lines of inquiry within the Szajkowski Collection that are now available for student exploration.

Can you describe some of the treasures you unearthed in the collection?

A highlight of the archive is the schoolchildrens’ drawings. They come from three separate Communist, Yiddish-speaking elementary schools that catered to children from the émigré, Jewish, East-European, working-class community in Paris. Members of this community relocated to Paris after a steep rise in pogrom activity in the Russian Empire after World War I.

Ideologically, however, many of the drawings show political orientations that are deeply loyal to Trotsky and the new Bolshevik state. There are some doodles and depictions of daily routines, but most of the sketches are political, in which children illustrate Soviet conceptions of fascist figures. These works, and the accompanying educational material also in the archive, provide a rare, unfiltered window into the pedagogy and political character of interwar Parisian Yiddish culture—a world where Bundists, Trotskyists, and Bolsheviks were all vying for supremacy within their shared Jewish community.

As mentioned earlier, the collection also contains the bulk of the French part of the Kultur Lige’s institutional archive, including official founding documents, information about theatrical and choral performances, school lesson plans and student workbooks, and cultural and literary events. There are endless fliers and pamphlets ranging from recruitment efforts for the Spanish Civil War to French immigration quotas and the rise of Hitler. The oversized posters are beautifully hand drawn, with striking Cubo-Futurist design graphics.

What will the March 27 event cover?

Our curatorial short program will in large part be about the schoolchildrens’ drawings. We will also include other features of the collection like the Kultur Lige posters, the extensive Spanish Civil War relief and recruitment efforts led by the Yiddish Communist community, and political cartoons from Yiddish publications in the early Soviet Union.

What lies ahead for you?

I have been living in Buenos Aires researching Jewish sex work and its intersection with religious ritual. I am here until December of 2023 to find out how the sex workers of the Zwi Migdal, a Jewish brothel and organized crime group active in Buenos Aires from 1890 to 1937, interacted with Jewish law and religious ritual—both within the brothel and within the larger Jewish community in Argentina at the time.

I plan to continue working in the field of Jewish studies in some capacity. As a historian, I believe the tools we need to better navigate the questions of the contemporary Jewish world can be found in prior iterations of Jewish worlds lost to the past. There is so much left to spotlight. I could see myself in academia, in the archive, or in education working toward those answers.