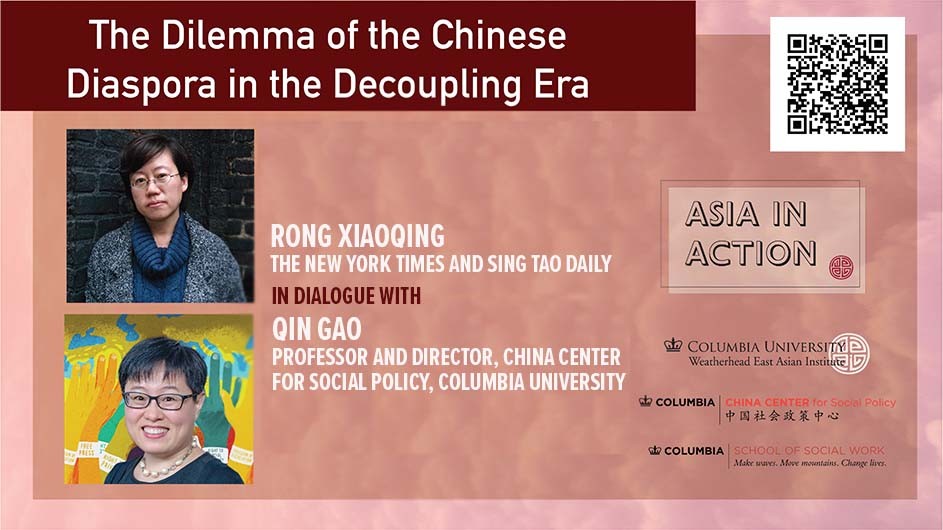

On October 15, 2021, journalist Rong Xiaoqing, a reporter for the Sing Tao Daily and author of The New York Times’ weekly newsletter, “Overseas Chinese Journal,” addressed changing U.S.-China relations, the impact of those developments on the Chinese diaspora community, and challenges as a reporter in an online event sponsored by the Weatherhead East Asian Institute. WEAI’s Qin Gao, professor and director of the China Center for Social Policy at the School of Social Work, was the moderator.

Xiaoqing’s wide-ranging talk opened with an anecdote from early in her time in the United States, when relations with China appeared to be on an upward swing. During a keynote speech at the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations conference in 2005, then-Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick referred to China as a “stakeholder,” much to the surprise of the event’s journalist attendees. This was also around the time that the term “Chimerica” was coined, a reference to the symbiotic economic relationship between the two countries. These days, Xiaoqing noted, the favored term for describing the future of relations between both countries is “decoupling.”

Today, as the U.S. government warns against espionage activities, Chinese students, scholars, and scientists working or studying in this country feel increasingly subject to scrutiny and accusations of spying. Additionally, people of Chinese descent living here are scrutinized online by Chinese netizens, often through a nationalistic lens. Ethnically Chinese people with a public platform “feel they have been pushed into a corner—that they have to choose sides,” Xiaoqing said.

Fear, Telling the Truth, and A Shared Sense of Identity

Xiaoqing described a sense of fear among members of the Chinese diaspora in recent years, which is related to speaking out and being targeted by the American authorities, and to expressing sentiments that would subject them to criticism from Chinese communities. This fear has made Xiaoqing’s job more difficult, as she balances journalistic integrity with the need to protect her sources. Professor Gao added that the reticence has also reached academia.

As a reporter, Xiaoqing said, her job is to tell the truth. “It sounds easy because there is one truth, but in today’s extremely polarized world, there is always the question: Whose truth are you telling?” Such questions translate into different value judgments about the veracity of her work depending on the publication and the audience she is writing for—Chinese, English, ethnic media, and more.

Other topics Xiaoqing covered included changes within the Chinese-American community, the integration and tension between Chinese-Americans and Chinese expats in the United States, anti-Asian attacks and discrimination, and pan-Asian identity.

While shifts in a shared sense of Chinese identity were discussed in depth, ultimately, Xiaoqing believes that the differences between us are smaller than we often seem to think they are. Just one year into her stay in this country, in 2001, the September 11 terror attacks occurred. Witnessing the solidarity and sense of community that permeated New York City in their wake shaped both Xiaoqing’s worldview and her appreciation of the shared humanity that underpins our diversity.

Ariana King is the communications coordinator at the Weatherhead East Asian Institute.