Why Do We Argue?

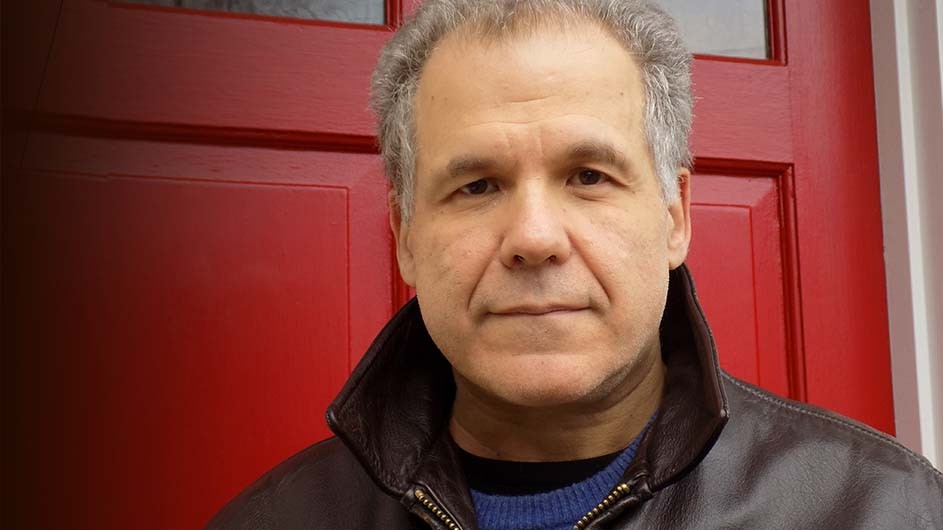

In his new book, Professor Lee Siegel explains that argument is at the heart of human experience.

From Eve’s exchange with the serpent, to Martin Luther King Jr.’s soaring ultimatums, and the throes of Twitter, the desire to prevail with words has been not just a moral, but an existential compulsion. In Why Argument Matters, Professor Lee Siegel, who teaches in the writing program at the School of the Arts, says that the art of argument is the supreme expression of humanity’s longing for a better life, full of empathy and care for the world and those who inhabit it.

Siegel plumbs the emotional and psychological sources of clashing words, weaving through his exploration the story of the role argument has played in societies throughout history. Each life, he believes, is an argument for that particular way of living. Argument is at the core of human existence, and language, at its most expressive, bends toward argument.

Siegel shares his thoughts about arguing with Columbia News, along with where he most enjoys reading, how often he’s read Invisible Man, and his choices for ideal dinner companions.

Q. What inspired you to write this book?

A. I'm at a place where I find fulfillment in taking stock of my life. Much of my existence as a writer has been spent making one sort of argument or another, as a critic, an opinion writer, or a polemical essayist—even as a memoirist.

So I wanted to examine this passion for argument, which has transported me since I was a child, to explore argument as a vocation, and to find its origins in the life around me. It seemed especially fitting now, when radical transformation in every area of society has people ceaselessly arguing with each other. What exactly is the true art of argument? How is it deeper and more embracing than mere quarrel, dispute, or debate?

Q. Can you give some examples from the book of the role argument has played in societies throughout history?

A. Buddha took on the Brahmins of his day in numerous arguments, one day challenging a Brahmin to explain why, if Brahmin women menstruate, have children, and nurse their children like any other woman, Brahmins consider themselves superior to every other class. Socrates used his new style of irony to burst the complacent certainties of the socially dominant Sophists. And Martin Luther nailed his famous theses to a church door, which was a spectacular coup de théâtre, a highly effective tool of argument.

American revolutionaries undermined their distant rulers in England with the brevity and speed of their pamphlets, while European figures like Voltaire and Schiller used the form of a letter to create an intimate bond with people alienated by impersonal monarchs. It's not just polemicizing: Raphael's portraits of the Madonna and Child are arguments for compassion as a form of perfection. And the first debate between Trump and Biden quickly descended into a verbal brawl, all the better to offer the wild, pent-up emotions of the previous four years the form of a public argument that everyone could step into.

Q. What is your ideal reading experience (when, where, what, how)?

A. In my office, at home, during the day, anything worth my time, in my beloved leather armchair, with my feet up.

Q. What's the last great book you read?

A. Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man, for the fifth or sixth time.

Q. What are you teaching this semester?

A. A lecture course on the picaresque novel.

Q. You're hosting a dinner party. Which three academics or scholars, dead or alive, would you invite, and why?

A. Donald Keene, the great Japanese scholar and translator who taught at Columbia for many years. I attended a gathering once where I heard him tell a marvelous story about the writer Yukio Mishima, with whom he had become dear friends. I would have loved to hear him tell more stories.

Conor Cruise O'Brien, the statesman and monumental biographer of another statesman, Edmund Burke. O'Brien was an intellectual who acted consequentially in the world. I am fascinated by people like that.

Aristotle, whose Rhetoric is still the classic work on the art of playing on an audience's emotions. I'd ask him how he came to be such a cold, manipulative bastard, and then make him a pasta puttanesca that he'd never forget.

Check out Books to learn more about publications by Columbia professors.