Columbia's “Brightest Star” in Philosophy, Seen in New Light

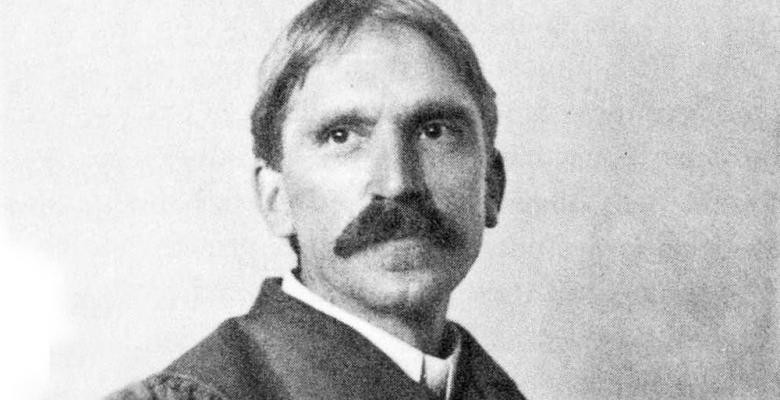

Few philosophers can boast of having their picture on a U.S. postage stamp. Or on the cover of Time magazine. Or merit a 3,349-word obituary in The New York Times.

Such was the fame and influence of John Dewey, the Columbia philosophy professor of whom Columbia historian Henry Steele Commager wrote in 1950 that “for a generation, no major issue was clarified until Dewey had spoken.” Once considered America’s leading liberal thinker, Dewey’s reputation has dimmed since his 1952 death, but one professor on campus is seeking to change that.

“The time is right for looking again at Dewey,” said Philip Kitcher, whose new book, Preludes to Pragmatism: Toward a Reconstruction of Philosophy (Oxford), makes the compelling case for reconsidering the importance of a figure whose stature extended well beyond academia.

Dewey was a leading exponent of pragmatism, an American philosophical movement emphasizing the practical consequences of ideas and beliefs.

He is perhaps best known today for his hands-on philosophy of education that emphasized learning by doing, an approach that helped lay the groundwork for progressive education today.

Kitcher’s interest in Dewey was spurred by a Columbia colleague, the late professor Sidney Morgenbesser, who suggested that the two shared philosophical affinities. It didn’t hurt that Kitcher is Columbia’s John Dewey Professor of Philosophy.

Like Dewey, Kitcher relates philosophy to wide-ranging areas of thought. For example, Kitcher examines the place of science in democratic societies and explores philosophical themes in music and literature.

He teaches undergraduate classes on Darwin, science and religion, and James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, in addition, of course, to Dewey. “I’ve always seen philosophy in connection with other things,” Kitcher said.

The British-born Kitcher came to philosophy after studying math and physics at Cambridge University. “I realized that I was not going to be a creative mathematician,” he said.

On a fellowship to Princeton he met his wife, Patricia, also a professor of philosophy at Columbia, specializing in Immanuel Kant and the philosophy of psychology.

What makes Dewey important to Kitcher? “He believed that philosophical questions ought to be connected to the conditions of people’s lives,” Kitcher said.

Dewey had things to say about birth control, vocational training and health care, topics still of intense interest today. He also personified the engaged intellectual, writing for mainstream audiences about the problems of the day.

Suspicious of grand theories, Dewey brushed aside certain longstanding philosophical questions as unproductive. For example, he thought the notion of certainty was neither achievable nor necessary. Philosophical progress, he once noted, can occur not by solving problems but by overcoming them.

Dewey’s views on education were honed at the Laboratory School that he founded in Chicago in 1896, where students might be asked to work with materials such as flax, cotton and wool in order to understand broader concepts about crop production, textile manufacturing and trade.

“He was part of a larger movement that rejected traditional rote memorization, but he was probably the most important in the field,” noted Larry Hickman, director of the Center for Dewey Studies and professor of philosophy at Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

Kitcher offers a related example, noting how Dewey saw gardening as an opportunity for young children to learn about plants, soil, chemistry, physics and social relationships. “Dewey considered that education, generally conceived, was the central problem of philosophy,” said Kitcher.

Dewey had a falling out with the University of Chicago president over differences in administration of the Laboratory School, which led to his resignation in 1904. He joined the Columbia faculty the next year with appointments in philosophy and at Teachers College, which this year celebrates its 125th year.

Dewey had already become famous in Chicago, but flourished even more as a public intellectual when he came to New York. He was a member of the NAACP from its inception, helped organize the American Association of University Professors and founded a group that later became the American Civil Liberties Union.

He took his educational insights abroad to countries including Japan and China and participated in the high-profile defense of Leon Trotsky, the exiled Marxist theorist and former military leader, in 1937. Dewey, by then nearly an octogenarian, conducted an inquiry that resulted in rebutting Stalinist charges against Trotsky.

He retired from active teaching at Columbia in 1930 and was named Emeritus Professor in Residence. His 90th birthday was celebrated at the Hotel Commodore in midtown with legions of well-wishers including U.S. Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, who spoke at the event. There were weeklong festivities on campus, where then-Columbia President Dwight D. Eisenhower called Dewey “the brightest star in Columbia’s firmament.” Kitcher says he worries that today’s philosophers are becoming too narrow and academic. “Following Dewey, I believe in the need for a reconstruction of philosophy so that it will not be a ‘sentimental indulgence for the few,’” he said.