A Digital Map of Historical New York Offers an Extraordinary Level of Detail

GSAPP’s Center for Spatial Research and the History Department team up to create the innovative website.

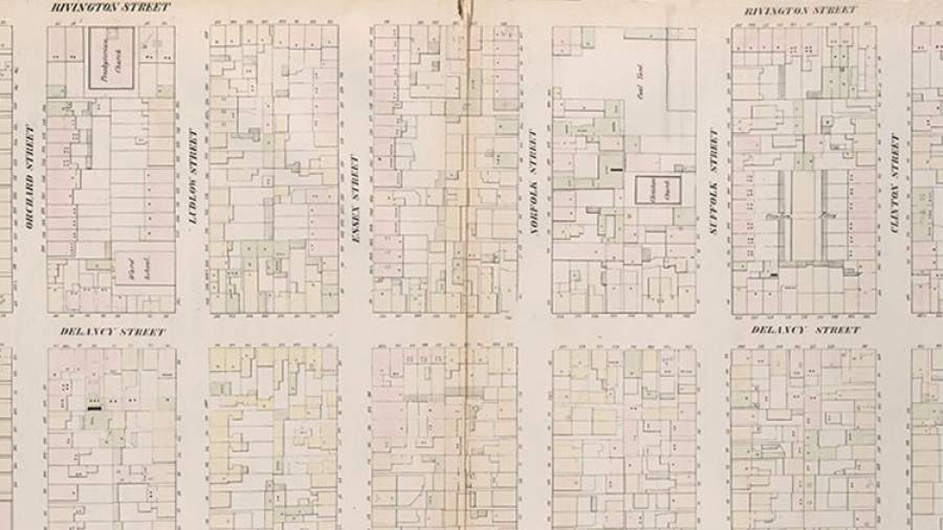

A glimpse into New York City at the turn of the 20th century can now be viewed at an exceptional level of detail: 6.5 million unique census records from 1850, 1880, and 1910 are pinpointed to residential addresses on the recently launched website Mapping Historical New York: A Digital Atlas. During these 60 years, New York City experienced a radical transformation due to an immigration surge and expansion into Brooklyn.

The interactive map visualizes Manhattan’s and Brooklyn’s transformations during this period, and shows how migration, residential, and occupational patterns shaped the city. The atlas also breaks new ground by locating each person counted in the census at their home address, sometimes before the street grid was even established. The ongoing project will expand over the next three years to include all five boroughs up to the 1940 census.

The atlas emerged from a multi-year collaboration between the Department of History and the Center for Spatial Research, which is part of the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation. Wright Kennedy, a postdoctoral research scholar, and Dan Miller, a research associate, led the project, alongside History Professor Gergely Baics, director of Urban Studies at Barnard; Rebecca Kobrin, Russell and Bettina Knapp Professor of American Jewish History; GSAPP Professor Laura Kurgan, director of the Center for Spatial Research; GSAPP Professor Leah Meisterlin; Mae Ngai, Lung Family Professor of Asian American Studies; and Dare Brawley, assistant director of the Center for Spatial Research. The team spoke about Mapping Historical New York, which is funded by the Robert D. L. Gardiner Foundation, at a recent virtual launch event, hosted by GSAPP.

Hull House Maps as a Source of Inspiration

“Today, massive amounts of data are available to facilitate urban studies, but their effective utilization has been hampered by two factors,” Ngai said. “First, urban historians and other scholars in the humanistic social sciences have traditionally been the least methodologically equipped to take advantage of the explosion of data that is now available. Second, while searchable microdata of all types are abundant and their use in GIS applications is now common, historical micro databases are only slowly being made available, especially for any period before 1970.”

Ngai cited the Hull House maps, a project led by social and political reformer Florence Kelley (1859-1932), as a source of inspiration for Mapping Historical New York. Kelley, together with other residents of the Chicago settlement house, Hull House, gathered information through door-to-door surveys about the inhabitants of their neighborhood, a congested area filled with tenements and sweatshops. The data—nationality, household number, income, and employment status—would later underpin discussions about labor law reforms.

“We have curated the data—and I’m using the word “curated” as a technical term for preserving and properly documenting data—so that it can be downloaded for research purposes to produce histories and analyses in many other formats,” Kurgan said.

Building a Historical Model

“We needed to find or create reliable reference data about a city we cannot visit without a time machine,” Meisterlin said. “We are working with census records, which we can’t verify.”

As a starting point, the team turned to IPUMS at the University of Minnesota Population Center, a database of census and survey records, and the New York Public Library’s collection of digitized and rectified historical maps. Rather than relying on an existing base map such as the Google Maps API, the team custom-built their own by tracing and geocoding buildings to specific addresses on fire insurance maps from 1850, 1880, and 1910.

“We built out historical coastlines and parks, everything that’s temporally sensitive, so it matches up with 1850,” Kennedy said.

As a workaround for the omission of residential addresses in the 1850 census, the team culled data from city directories and documented routes walked by enumerators. By employing fuzzy matching techniques, they were able to merge data from different historical sources to form a more complete historical record of New York City.

Instead of a name, each individual is labeled with a unique identification code on the digital atlas, due to the project’s data sharing license with the University of Minnesota Population Center. However, users can plug in addresses associated with an individual’s genealogical record to view the demographics of their residence and neighborhood. An overview of the data creation and visualization process is outlined on the Mapping Historical New York website, and the team intends to write about their methods in greater detail so that cartography and history enthusiasts can build upon their innovative methods.

“We see this map as a conversation that will grow with your use of it, your questions, and your insights,” Kobrin said.

Microdata Case Studies

“Each person is represented by one dot, and those dots centered around their respective building addresses, to our knowledge, form an unprecedented high-resolution census visualization, especially in covering such a wide area. This allows us to ask questions about density, diversity, segregation, and social stratification,” Meisterlin said.

A selection of case studies presented on the Mapping Historical New York website illuminates the degree to which microdata can yield new insights into New York City’s historical records. Farm to City Brooklyn, for instance, zeros in on Brooklyn’s Flatbush Avenue, and visualizes a rapid transformation in the demographics of Kings County from 1880 to 1910 as its agricultural industry, which largely relied on Black and immigrant labor, was absorbed into a dense urban street grid. The team encourages students and scholars to develop more case studies, which can be included on the website. A forthcoming digital tool will enable users to download data for their research.

Historical U.S. census records are, of course, imperfect. Standardization of the enumeration process didn’t arrive until 1830, and before 1960, censuses relied entirely on door-to-door surveys. Inevitably, errors resulted due to linguistic barriers and miscommunication, as well as the omission of seasonal workers and residents without legal status. Taking these issues into account, Kobrin estimates that the census data depicted on the digital atlas accounts for 60% to 70% of the actual residents in New York City at the time; the degree of error varies by location.

“Carrying out this project while the 2020 census was unfolding was troubling and illuminating,” Miller said. “Just seeing it resonate with the 1880 census, and with the 1910 census that we’ve been working so closely with, has made me think a lot more about data collection practices and processes."

The Impact of the Great Migration

Mapping Historical New York will soon be expanded to include microdata for an enlarged area and time span—all five New York City boroughs from 1820 to 1940. The earlier start date will include the end of slaveholding in New York and newly freed Black Americans. By extending the digital map through 1940, “we hope to show the impact of the Great Migration of African Americans from the South to New York after World War I, as well as migrations from Puerto Rico and Jamaica,” Ngai said. The ever-growing collection of microdata is being preserved for posterity by Columbia Libraries.

“The most important lesson I learned from this project is the extraordinary power of micro, individual-level data,” Baics said. “I believe that the future of social science research and social science history is based on this sort of data, which allows us to examine social phenomena at the individual level, and also on a large scale.”

Shannon Werle is the digital editor in the GSAPP Communications Office.